In 1953, Francis Bacon’s friends Lucian Freud and Caroline Blackwood were concerned about the painter’s health. His liver was in bad shape, he drank inordinately, his lover had recently thrown him out of a first-floor window in the course of a drunken row, he was taking too many amphetamines and his heart was ‘in tatters’, ‘not a ventricle working’. His doctor had warned if he took one more drink, he informed them over dinner at Wheeler’s restaurant in Soho, he might drop dead on the spot. Then, in ‘an ebullient mood’, the artist ordered Champagne.

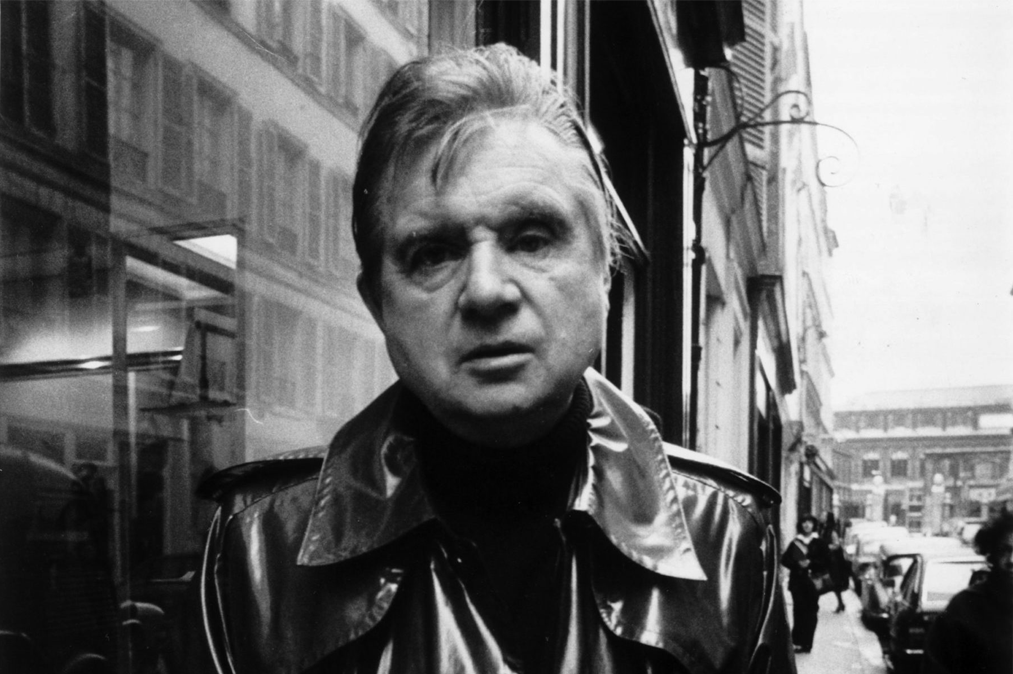

Of course, Bacon (1909-92) didn’t expire on the spot. Instead, he lived, painted, drank and argued for another four decades. The anecdote is typical of Bacon in its high-spirited posturing on the edge of the abyss, and also in the way it makes one wonder about the facts related. Was Bacon’s doctor really that concerned?

One difficulty for this new biography, and all writing on Bacon, is disentangling the truth of his (always vividly and brilliantly expressed) self-made myth. He was a charismatic talker, and a good deal of the time he didn’t spend at his easel was passed in dialogue with friends, fellow artists, strangers he met in the pub and anyone who took his fancy. And, like all good conversationalists, he was prone to improve mundane events to make them more interesting. Another problem is that virtually everything he said has disappeared, leaving only a few hazy memories.

Frank Auerbach has recalled how he ‘liked making statements, formulating dogma, laying down rules; of course they changed all the time’. It would be fascinating to read a transcript of these colloquies, a little wild and drunken as Auerbach described them. But in common with almost all of Bacon’s words, they vanished into the air, leaving mainly formal interviews, in which Bacon tried to avoid being pinned down, and the occasional letter. So writing his biography poses problems. On the other hand, what a subject it is: an almost mythic tale, beginning in a Georgian house in Edwardian Ireland, a stultifyingly philistine, hunting, shooting and racing household, in which Francis was the rejected weakling of the litter. His father was an irascible ex-army officer, for whom Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan’s favorite adjective is ‘simmering’. Francis even managed to be allergic to dogs and horses. Whether Major Bacon actually instructed his grooms to thrash his unsatisfactory son and ordered him out of the house at the age of 16 when he caught him dressed in his mother’s underwear — or if Bacon just felt these things ought to have happened — we will never know.

From this point, virtually uneducated, and without any discernible aims, Bacon managed to transform himself into one of the towering figures of 20th-century art, not just in Britain but internationally. This took sometime, as well as economies with the facts. His career, Bacon told the critic David Sylvester, was strangely ‘delayed’. He was in his mid-thirties before he really began to establish himself as a painter. One of the achievements of this biography is to have filled in a great deal of detail, especially about Bacon’s childhood and life before his surprisingly late emergence.

The authors have, for example, discovered a hitherto unknown lover: Eric Allden, ‘an upstanding member of the Tory establishment with some years in government service’. He met the 20-year-old Bacon, then a would-be furniture designer, while crossing the Channel and was taken by his ‘big childish pale blue eyes’. For the first half of his life, Bacon seems to have been searching for a substitute mother and father, more suitable and affectionate than his actual parents. That would explain Bacon’s passionate attachment to his childhood nanny, Jessie Lightfoot, who came to live with him in London, sometimes sleeping on the kitchen table, and whose death in 1951 seems to have affected him at least as deeply as any other loss he suffered.

This is by no means the first biography of Bacon. He fended off such publications during his lifetime, but a spate appeared soon after his death, and more contributions have come along since (including from me). Some of the others, written by people who knew and drank with Bacon, have a stronger sense of that unique personality, described by the painter R.B. Kitaj as ‘a stunning creature, a kind of mutant’, who moreover sought to stun his audience (both with words and paint, one might add). Revelations is, however, by some way the most thorough and painstaking version of Bacon’s life to date. It adds a great deal of detail and corrects numerous misconceptions. The writing is always elegant and the works are sensitively described. Yet… Bacon often spoke of his attempt to ‘trap’ his subject, so as to capture the sense of its vitality ‘more vividly’. Here that doesn’t always happen; on the contrary, like one of the blurred figures in his paintings, Bacon seems to be in the process of escaping.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2021 US edition.