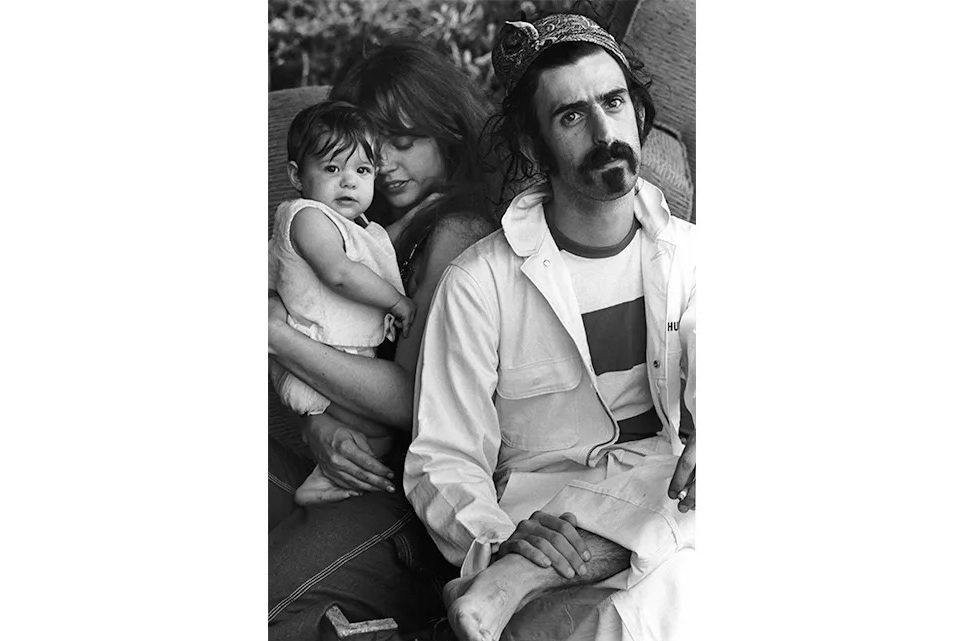

On Frank Zappa’s first date with Gail Sloatman, he blew his nose on her skirt. As acts of territory-marking go, it’s hard to imagine something more equivocal. But Gail, a twenty-year-old secretary at Los Angeles’s Whisky a Go Go club, must have read it as love. She built her life around the musician, composer and “rock’s most committed iconoclast,” as his New York Times obituary described him, for twenty-seven years, until his death from prostate cancer in 1993, aged fifty-two.

A year after that first, snot-filled seduction, the Zappas were married, a week before Gail gave birth to Moon Unit, the first of four children. Moon’s name is not a compound noun: Unit is her middle name, given to reflect how her arrival turned two people into a single family — Frank’s idea.

Moon’s memoir is partly a meditation on a lost milieu, a portrait of the Laurel Canyon countercultural landscape of the 1970s and 1980s, made lucid through a child’s eyes. But the Los Angeles setting is less important than the grimness of the family’s home life. This is mostly the story of a disastrous marriage, endless battles, a dysfunctional upbringing and children trapped by their parents’ unhappiness — even as adults.

Moon is now fifty-six, and still famous by association, but she can certainly write. Her strengths are her sense of the absurd, and an ability to conjure a scene from decades’ old memory in a way that feels lucid and real. It would be tempting to attribute the former to Frank’s legacy, but it was Gail who read to Moon and encouraged her to read, notably Dr Seuss.

Like many abusive parents, however, Gail is never one thing. She oscillates between affection and fury. She threatens and manipulates. She vanishes, leaving her children with useless babysitters. When Moon and her brother Dweezil, bicker, Gail handcuffs their ankles together then records their screams and plays them back to them to “see how you like it.” When Frank is dying and Moon is near deranged with grief, Gail demands that her daughter sell her house to pay his medical expenses, presenting it as a bill for the cost of her upbringing.

Intriguingly for the period, there is very little rock’n’ roll excess: alcohol and drugs are barely mentioned. Frank’s extraordinary capacity for work (he released sixty-two albums in his lifetime) meant he was unlikely to have had the time. Consequently, he is a shadowy figure, nowhere near as vivid as Gail, either absent on yet another world tour or lurking in his basement recording studio, where the children understand that he is not to be disturbed. But his sexual appetites are always prioritized. At one point he moves a groupie into the studio, and his family seems to quietly accept it.

One of the most engaging episodes deals with “Valley Girl,” the 1982 single and Frank’s biggest US hit, which is credited to Frank & Moon Zappa. It is a sharp, funny, post-punk critique of the wealthy brat-girls that both surround and ostracize the adolescent Moon. The lyrics, touching on light S&M, would be a questionable choice of subject matter for a fourteen-year-old today, but not so in the 1980s. And Moon is a gifted mimic, mocking her contemporaries’ affectations in snatches of dialogue. “Valley Girl” led to a kind of fame for her: TV appearances, chat shows and eventually a presenting gig on MTV. At last she has her father’s attention, but Gail is never far away, whispering to her daughter that the world only cares about her because she’s a Zappa.

I would have liked more curiosity about Frank and Gail’s early lives. Little space is given to exploring why Gail was such a “mean mom,” or why Frank was able to offer his children only “underwhelming, semi-cool attention.” Presumably they were not born dysfunctional, and they would have told their stories differently. Was Gail’s spite the result of stifled ambition, loneliness, drudgery and living with a serially unfaithful husband? She may be the villain of the piece, but Frank is not exonerated. In a telling line, Moon writes that her father (and the wider culture) left her young adult self with “the steady message that women have feelings that don’t matter, that women are sex toys wrapped in lies about female empowerment.” Or did Frank withdraw from his family because of Gail’s coercive control over money? She was his business manager as well as his wife. He tries and fails to leave her countless times. Did he stay for the children’s sake or his own?

Moon seems to believe that her mother possibly ignored a will found in a drawer, in which Frank divided his estate between his family and told them to enjoy their lives. Instead, Gail took charge of everything, was horribly in debt at the time of her death in 2015 and left her children unequal shares in their father’s legacy. Her odd favoritism still seems to cause tension between the Zappa siblings.

This self-excavating memoir often uses the language of someone who has spent years in therapy. Moon is a product of Hollywood, despite her unnerving ability to savage its grotesques, describing her young self as “a puppet, a parrot, dressed up for show.” In later chapters she verges on psychobabble, particularly those dealing with the arguments over her father’s legacy.

She can be forgiven for that. Finding any sense of herself amid Frank’s misogyny and commitment to living as an iconoclast and Gail’s relentless misery must have taken a lifetime’s struggle. She is still living with their battles.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply