Hud is a film that has haunted me for decades. I was never sure why. It seemed to be something about the bleakness of the setting and the story but also the extravagance of the hero and his car. I recently watched it as research for a book, and then, immediately, I watched it again. It is that good. There are two stars of Martin Ritt’s movie: Paul Newman and a 1958 Cadillac Series 62 Convertible. Out there in the ranchlands of the Texas Panhandle New-man looks just fine — big hat, jeans, cowboy shirt and boots — but the car looks all wrong. It is long, low and wide with an absurd pair of tailfins. Moreover it is pink. Though the film is in black and white, the Caddy’s pinkness is mentioned twice in the dialogue. It should be like everybody else’s vehicle in those parts — a Dodge truck, bouncing over the ruts in the dusty roads. The Caddy doesn’t bounce, it wallows and slithers round corners. It is a terrible car and it is no surprise that, in one of the final scenes, it fails to start. But it’s a seducer’s car and Newman’s character Hud is, above all, a seducer. He is first seen leaving the house of a woman just as her husband arrives. Later he attempts to nail Alma, his father’s housekeeper, even to the point of a drunken attempted rape. Hud is a drunk, a rebel, a cynic and a cold-hearted manipulator, a very 1960s hero. There are many such characters in films; here Newman is the best of them all. The film was widely appreciated when it came out in 1963, winning multiple awards including three Oscars — though not, absurdly, for Newman. Martin Ritt, who died in 1990, always knew what he was doing. His films have a finished quality, as if they could have been no other way. Hud is probably his masterpiece. Hud is the son of Homer Bannon (Melvyn Douglas), and together they run the Bannon cattle ranch. Hud’s young nephew, Lonnie (Brandon deWilde), is torn between loyalty to honorable, high-minded Homer and his rogue uncle. That dynamic, combined with the erotic tension provided by Alma (Patricia Neal), is the inner core of the plot. The outer core, believe it or not, is an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in Bannon’s cattle. Hud insists that Homer send the cows north to be sold before anybody finds out. Homer refuses, stolidly holding on to his law-abiding beliefs. To Hud’s disgust, he prevails, and in the wonderful climactic scene all the ranchers gather to shoot the cows that have been herded into a vast pit. Only two of Homer’s beloved longhorns are left and the sorrowful authorities allow him to shoot them himself. Hud cuts through this action like a Bowie knife, providing a sneering commentary on everything while attempting to debauch Lonnie with drink and women. To Alma he offers an apology, but that’s about as good as he gets. He fails at everything in the end, but this is no victory for virtue. With a flick of his hand, Hud seems to dismiss the entire cast, including his busted Caddy, and moves on. The film is shot in a very bleak and unyielding monochrome. The dialogue is spare and direct: ‘I just naturally go bad in the face of so much good,’ says Hud, comparing himself to Homer. The soundtrack is interspersed with mooing cows, cowboy music on tinny transistors, the roar of trucks and the groaning and wallowing of the pink Caddy. Everything fits, everything addresses the mood of the place and the quiet desperation of the theme. The Caddy is in the wrong place and so is Hud. They are both unsuited to the dust and death of the Panhandle; they should be wallowing together in the lies and hustles of the big city. But, still, you know, as he flicks his hand and the screen door slams, Hud will never go there. He is too much at home where he is least at home. This article was originally published inThe Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.

Newman’s own

A pink Cadillac in the Texas Panhandle

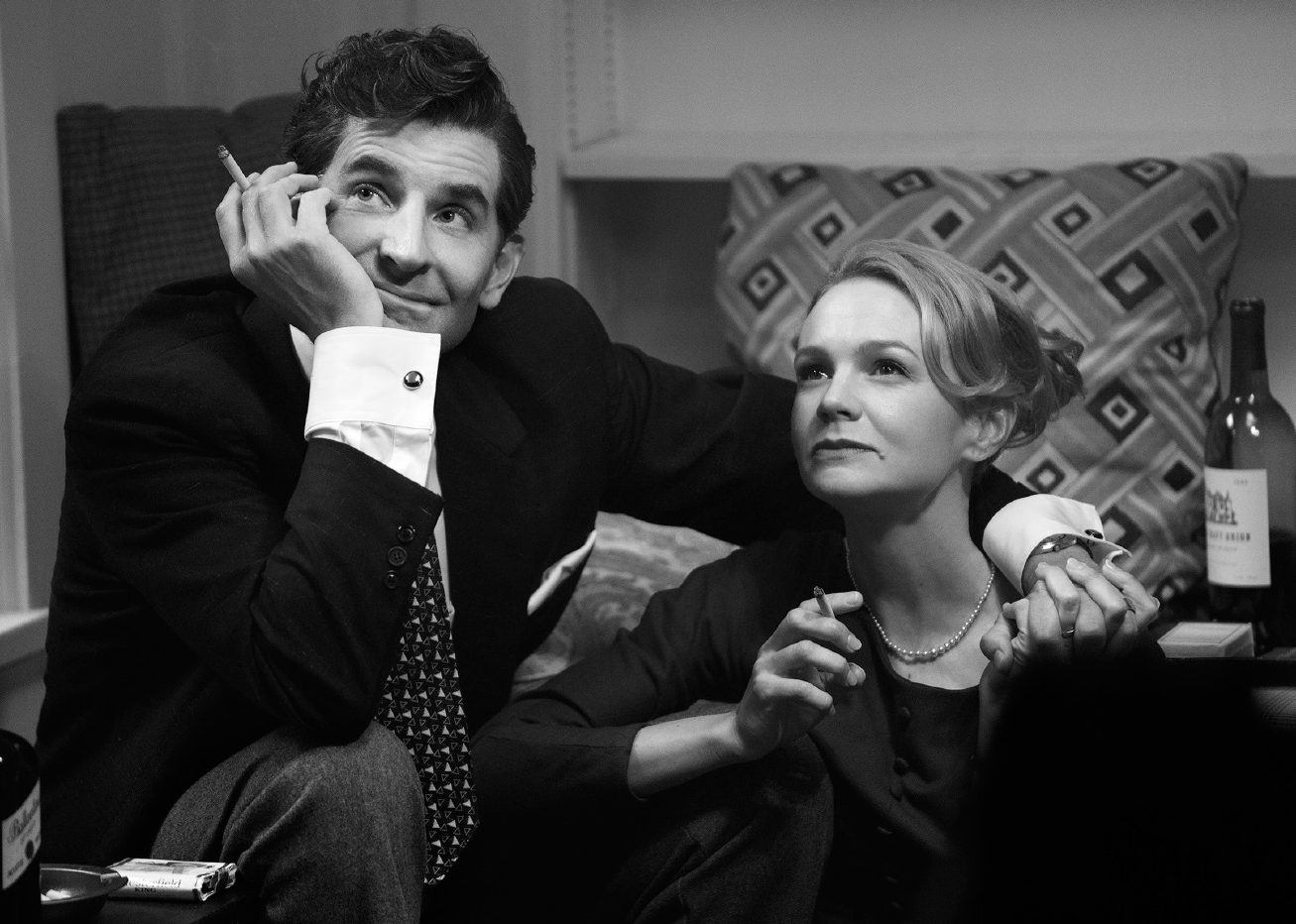

‘I just naturally go bad in the face of so much good’: Paul Newman as Hud in Martin Ritt’s masterpiece. Photo: Granger/Shutterstock

Hud is a film that has haunted me for decades. I was never sure why. It seemed to be something about the bleakness of the setting and the story but also the extravagance of the hero and his car. I recently watched it as research for a book, and then, immediately, I watched it again. It is that good. There are two stars of Martin Ritt’s movie: Paul Newman and a 1958 Cadillac Series 62 Convertible. Out there in the ranchlands of the Texas Panhandle New-man looks just fine — big hat, jeans, cowboy shirt and…

Comments

Share

Text

Text Size

Small

Medium

Large

Line Spacing

Small

Normal

Large