First disclosure: I do not appear in this book. I say that only because — second disclosure — I consider myself a YIMBY, and I am familiar, at least online, with many of the characters and figures quoted or interviewed. However, I learned a lot about this loose movement and found it fascinating to read a book on a phenomenon that I would have trouble viewing with a detached, scholarly distance.

Yes to the City, by the cultural sociologist and urban policy scholar Max Holleran, must have been a difficult book to write, not least because YIMBY (“Yes in my backyard”) is as much a rallying cry or a slogan as it is a movement, let alone an organization. The YIMBY nemesis, NIMBY (“Not in my backyard”), is equally amorphous. There are antigrowth organizations or coalitions formed to stop this or that project, but NIMBYism is also a sentiment — often a vague one — that a place is good enough as it is and that new growth should just go somewhere else.

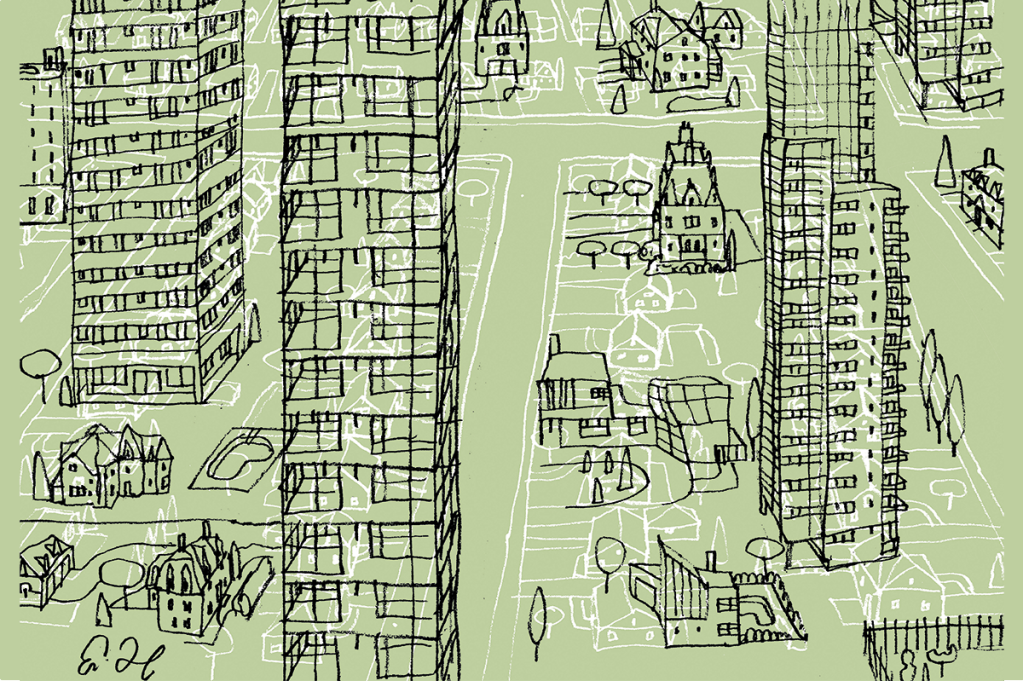

YIMBYs, on the other hand, accept and even encourage urban growth, seeking to put it where it makes the most sense. That means “smart growth” close to commercial and cultural amenities, transit and, of course, other people. YIMBYs are champions of the city in the abstract, and of the energy and cosmopolitanism of urban life in particular. They chafe against restrictive zoning codes that favor single-family homes over most urbanized land. They believe building more housing will check prices. They tend to be millennials, as well as relatively high-earning and highly educated. They are also largely white. Their most frequent rivals might well be their own parents — boomers with million-dollar houses bought decades ago for a song who have no idea what it’s like to look for a home in a growing city in the twenty-first century.

All of this is political, in the sense that urban planning and policy are political, but it isn’t necessarily partisan. You might, for example, associate NIMBYism with conservatism. YIMBYism emerged in San Francisco, the center of America’s most acute housing affordability crisis. Generally YIMBYs are left-leaning (with some property-rights/deregulation libertarians as well). But most of the NIMBYs in the Bay Area they butted heads with were also on the left, including, in many cases, old-line anti-gentrification activists who feared that new housing would result in displacement of existing largely working-class and non-white communities.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]The key point, however, is that in the birthplace of YIMBYism, pro- and anti- growth arguments largely transpired within the left. While YIMBYs have found race and gentrification tricky issues, they have been largely successful in making an older generation of lefties appear hypocrites. “The desperate scramble to protect home values reveals a kind of left-wing double standard,” Holleran writes, “in which empathy is something saved for those who live far away and with whom one does not have to share parking, schools, and hospitals.”

For someone without a prior interest in housing or urbanism, let alone insider knowledge of how YIMBYism plays out on the internet (lots of memes and snark, appeals to American “middle-classness” next to arguments that millennials have been shafted), much of Yes to the City might be disposable. Perhaps the most important chapter for a casual reader is the one on Boulder, Colorado, and the history of its environmentalist, anti-growth greenbelt program.

Greenbelts, arising in the UK in the early twentieth century, are forests or farmland ringing towns or cities on which no development is allowed. The goal is to preserve the countryside and prevent urban sprawl. So far, so good. YIMBYs would argue that, with the potential for sprawl cordoned off, the city should then densify and grow upward, at least to some degree. But that isn’t what happened; Boulder’s greenbelt was part and parcel of an environmentalist anti-growth agenda, which included concerns about overpopulation.

And what’s more, that agenda only accelerated sprawl. As Holleran suggests, “combined with height and density limits — spurred by the impulse to keep newcomers out of Boulder’s Edenic center — the greenbelt keeps neighborhoods from expanding in any other direction except for leap-frogging over it.”

Conservatives, especially those who consider themselves pro-life and pro-family, should be concerned that so much NIMBYistic, anti-growth sentiment came historically from the left and was tinged with misanthropic concerns about population growth. Holleran notes a slick bit of rhetoric YIMBYs came up with during the Trump years: progressive NIMBYs, who wanted to keep newcomers out of their neighborhoods, weren’t so different from the forty-fifth president, who wanted to keep newcomers out of America altogether.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]With that point raised, does YIMBYism translate to the suburbs, or to American small towns or small cities — say, conservative-leaning places with five thousand, ten thousand, thirty thousand people? Despite living in cities, many of their inhabitants are skeptical of urbanism. Holleran doesn’t have much to say about this, but that may be because YIMBYs in general, concentrated in America’s growing, unaffordable cities, don’t have much to say about it, either.

Holleran writes that YIMBYism represents a “twinning of millennial politics and urban planning priorities.” He also argues that millennials have made “social choices that fit more naturally into city life,” such as renting, cohabitating, delaying marriage and — though he doesn’t mention it — having fewer kids, later in life, or eschewing children altogether. This framing would seem to validate conservatives who view urban life as immature, or cities as playgrounds for rootless, barren, secular consumers. There is, however, a whole genre of urbanism that argues that cities are family-friendly, as well as a raft of social conservatives who are increasingly amenable to urbanist arguments once the domain of the left. It would have been fascinating if Holleran had mined this vein of commentary.

His overall framing of YIMBYism is roughly accurate but is perhaps influenced more by the movement’s technocratic, very-online aura than the actual substance of its recommendations. Holleran suggests several times that the YIMBY movement is something new or unique in housing discourse: with its focus on generation rather than class, or with its supply-side emphasis of “build more housing” rather than focusing on controlling prices directly or subsidizing public housing.

But is it new? Most YIMBYs would like to deregulate land use, at least to some extent, and make organic urban growth easier — as it was when most American towns and cities were substantially built. The idea that YIMBYs are highly educated technocrats who seek “capitalist solutions to the housing crisis” may be true, but what many understand themselves to be doing is tweaking the current morass of land-use regulation in order to reverse-engineer, or at least approximate, the pre-zoning American status quo of building cities.

YIMBYs “see a state role for transit, coordination of growth, and managing environmental resources, but they eschew the idea that local or state government will become large-scale landlords or developers,” he writes. Well, yeah. Where did the idea come from that most housing in the United States would ever be built or administered by the federal government? Holleran suggests “the moderation of the YIMBY movement may prove to be its greatest vulnerability.” For a book that is mostly fair and even positive, it’s nonetheless oddly suffused with the notion that there’s something vaguely disreputable about not being radical.

Holleran also intimates, in his final chapter, that YIMBYs may not be going far enough toward “decommodifying housing.” That phrase (not coined by Holleran) is odd. Commodities are cheap and easily traded. Coal is a commodity. Oranges are commodities. If some people can’t afford oranges, you offer them the SNAP program; you don’t abolish the orange industry. In the actual YIMBY view, the problem isn’t so much that housing is commodified, as that it isn’t — every ordinary suburb or neighborhood sees itself as a special place that must insulate itself from any change and encase its zoning and land use in amber.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Holleran may see himself as critiquing YIMBY “moderation,” but it’s more likely that he just feels an ideological disagreement with it. Much of his final chapter betrays a radicalism that would rightly frighten most ordinary Americans and which, if embraced by urbanists generally, would see their movement marginalized and ridiculed. Americans are not “ready to rethink… private ownership.” They will not welcome granting eminent domain for the state to “tear down exurban areas.” Yet only a few pages before these endorsements, Holleran mocks right-wingers for claiming that the American left wants to “abolish the suburbs.” Holleran’s critique of YIMBYs from the left is like a NIMBY fever dream.

Luckily, the YIMBYs are in the middle.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2022 World edition.