One of Joseph O’Connor’s strengths is his magpie-like approach to history: he plunders it for stories that he can rework as fiction. His new novel is based on the exploits of Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty, a senior official at the Vatican, who, together with colleagues, was responsible for saving the lives of 6,500 Allied soldiers and Jews after the Nazis occupied Rome in 1943.

It is by any standards an extraordinary tale. O’Flaherty’s organization called itself the Choir; the prisoners it sheltered were known as Books, and their hiding places, scattered across Rome, as Shelves. The priest was constantly at risk from the Gestapo, as were his helpers, who included Britain’s deliciously camp ambassador to the Vatican, the ambassador’s artful cockney butler, Major Derry of the Royal Artillery, and the ballad-singing wife of the Irish ambassador.

The narrative focuses on a large rendimento, a complex mission designed to bring about the escape of prisoners from Rome. Timed for Christmas Day, the preparations and the evacuation itself form the narrative spine of the novel. The other main viewpoints are fictional — a Swiss journalist, a resourceful Italian stallholder and a glamorous widowed contessa. For good measure, O’Connor throws in an equally fictional version of Rome’s Gestapo chief, Obersturmbannführer Hauptmann.

To make matters more complicated, not to say confusing, the main story is peppered with sections set twenty years later, when the characters (real and fictional) reflect on these events in preparation for a BBC’s This Is Your Life program in honor of Major Derry.

O’Connor has clearly done his research, and his raw material could hardly be more dramatic. He’s a fine novelist, capable of remarkable feats of literary ventriloquism. Some chapters are written with great power. There’s a chilling scene when Pope Pius XII furiously upbraids O’Flaherty for putting at risk the physical integrity of the Vatican.

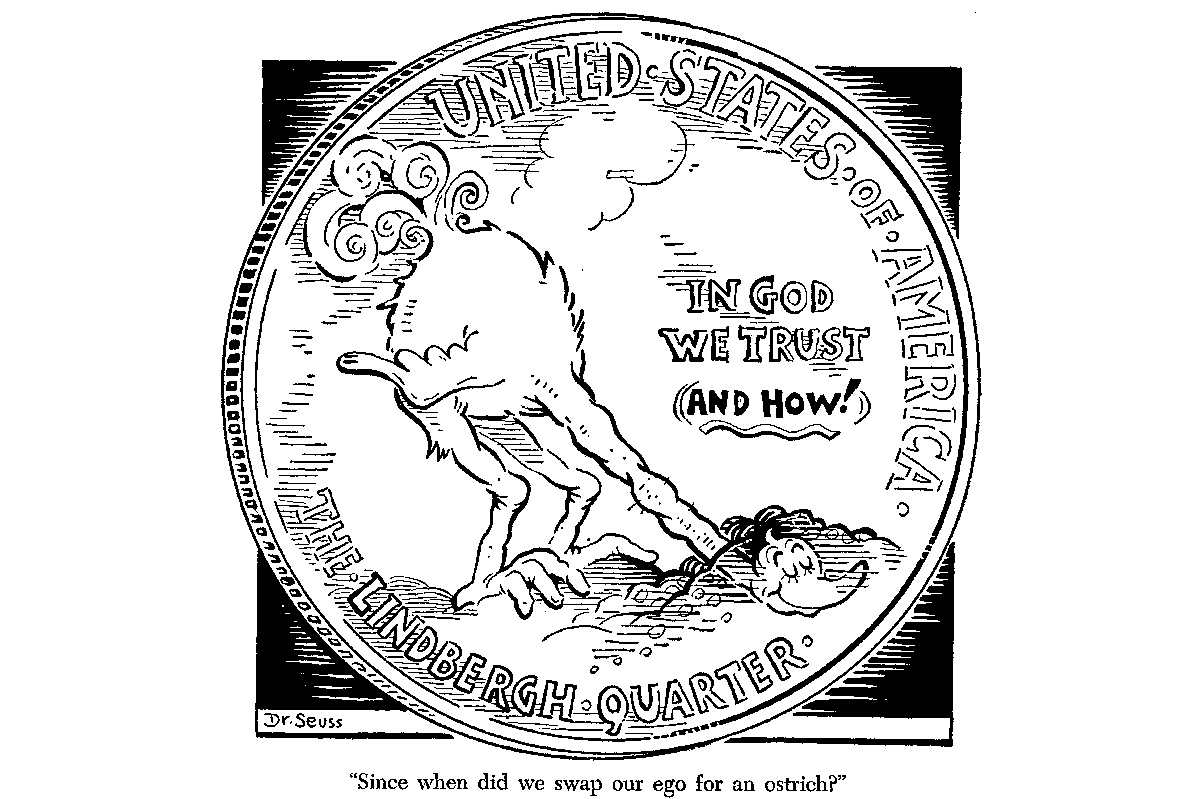

But the no man’s land between fact and fiction is a murky place, difficult to negotiate and strewn with pitfalls. This is partly why the book as a whole is curiously unsatisfactory. The text is sprinkled with overwrought sentences that try too hard, such as “The fox of his fears prowls a carpet of broken glass,” and with words that have you continually reaching for the dictionary. Sometimes you yearn for a homespun verb.

The main problem, however, is the story’s structure. The leaps forward into the 1960s reduce almost to vanishing point the tension of the wartime narrative. By the end you can’t help thinking that the Choir deserved a better memorial.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.