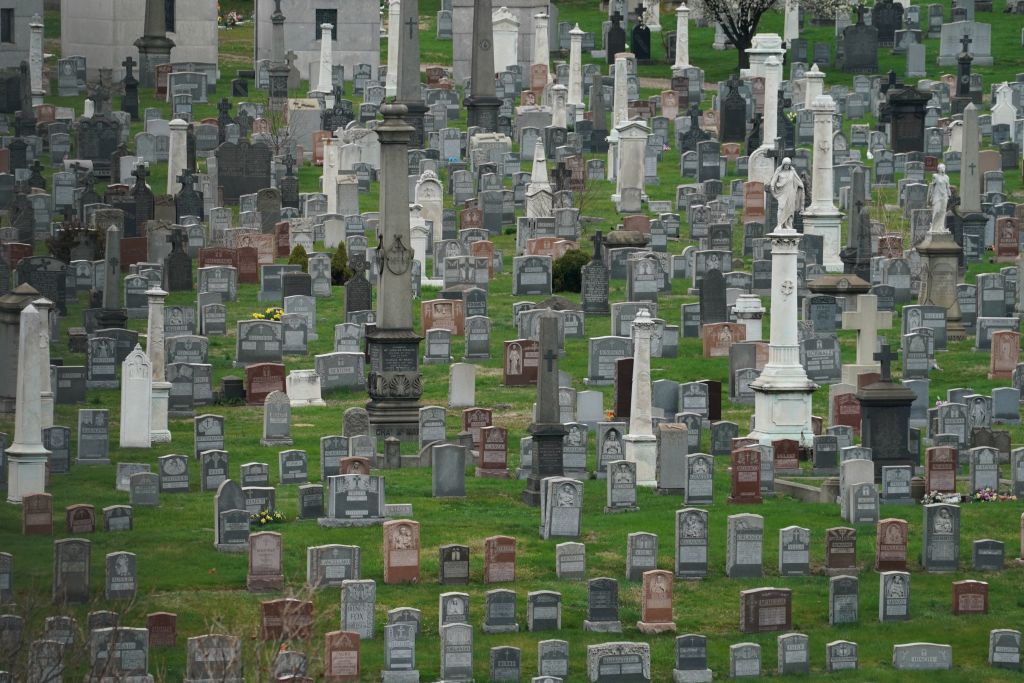

Dying sensibly has always eluded Americans — from Elvis to Houdini — and that’s before you even get to the funeral part. In fact, in America, something peculiar has occurred over the last century. Traditional obsequies have fallen out of favor as Americans increasingly opt for “anything but” the conventional when it comes to final resting places: that is, no more six feet under.

According to the National Funeral Directors Association (NFDA), the majority of Americans now choose cremation, with the rate expected to surpass 80 percent by 2045. Ecofriendly departures — think hemp coffins or ashes strewn over a living coral reef — are also becoming more popular; 60 percent of respondents to one recent survey expressed an interest in “green funeral options.”

Such statistics would have greatly intrigued Jessica Mitford, author of The American Way of Death (1963), the groundbreaking — if one may be allowed — exposé of the nation’s funeral industry as it stood then.

The book caused pandemonium in the undertaking business. Its publication was considered so detrimental to industry profits that funeral directors damned it as “the Mitford bomb,” “the Mitford missile,” “the Mitford war dance.”

For all this hyperbole and Mitford’s own sardonic flair (she branded them “small-time crooks” and “Dismal Traders”), the book’s message was simple: the expensive frills of the twentieth-century commercial funeral are superfluous and the monetary exploitation of grief by an entire industry constitutes day- light robbery. Some sixty years after its publication, the ethical concerns of The American Way of Death still resonate. The US “death care” market is estimated to rake in about $20 billion annually.

One may wonder how shuffling off this mortal coil could turn out to be so lucrative.

But money rarely explains the whole. Far better to turn to literature.

The American Way of Death is littered with scholarly references. John Donne, Sir Thomas Browne, Shakespeare, Dickens and Evelyn Waugh all feature prominently, although their greatest quotes are reappropriated in service of Mitford’s biting satire. Most irreverent is her repurposing of poor Yorick as she imagines how surprised that humble skull would be

To see how his counterpart of today is whisked off to a funeral parlor and is in short order sprayed, sliced, pierced, pickled, trussed, trimmed, creamed, waxed, painted, rouged and neatly dressed — transformed from a common corpse into a Beautiful Memory Picture.

The beautification process described above can be ascribed to a culture of embalming that until very recently — the last few decades or so — remained the status quo due to widespread demand for open-casket funerals. As the ebullient director of Whispering Glades Funeral Home, Mr. Joyboy, relays to his client in Waugh’s satirical novella The Loved One (1948), embalmers can fix anything: “hair, skin and nails … I brief [them] for expression and pose.” His English protagonist, the poet Dennis Barlow, is more blunt: to be embalmed is to be “pickled in formaldehyde and painted like a whore.”

When Mitford was asked what kind of funeral she envisioned for herself, she said, “Oh, I’d like six black horses with plumes, and one of those marvelous jobs of embalming that take twenty years off.” Given the rise of cosmetic surgery, perhaps this generation will save undertakers the job of post-mortem facelifts; thanks to Botox, our faces will remain plastic and perky ad infinitum.

Despite recent moves against the procedure, America’s love affair with embalming has deep roots. Though not the “pushing up the daisies” kind (too many toxic chemical preservatives). The practice first took hold during the American Civil War to ensure fallen soldiers might be returned home for one last face to face farewell. In his apocalyptic Americana joyride American Gods (2001), Neil Gaiman traces this lineage by imagining the ancient Egyptian god of mummification and the dead, Anubis, working as a funeral parlor technician in Cairo, Illinois. Mr. Jacquel (Anubis) and his partner, Mr. Ibis (the Egyptian god of wisdom, Thoth) appropriately open their funeral home in 1863, slap bang in the middle of the Civil War. Gaiman’s novel is not, however, a historical romp across North and South but a phantasmagorical deep-dive into the psyche of modern America. So, when Mr. Ibis claims, “death is an industry… make no mistake about that,” he speaks as a businessman. The trouble, he says, is that “no one wants to know that their loved ones are travelling in a cooler-van to some big old converted warehouse where they may be twenty, fifty, a hundred cadavers on the go. No sir.” No sir, indeed.

Increasingly, when modern America talks of death, it chooses to ignore its earthy, ugly, physical reality. Waugh poked fun at what he saw as America’s propensity for nauseating euphemism in The Loved One. At Whispering Glades — the fictional necropolis based on Forrest Lawn in LA — the words “body” and “cadaver” are banned outright. Instead, the deceased are always “the Loved Ones.” Those who pre-plan their own funerals are even more unnervingly “the Waiting Ones.” There’s no anthropomorphized Grim Reaper to be found here. Death must remain abstract, for that way it has no sting. As Mitford wryly observed, there are never burial provisions made for “a Heartily Disliked One.”

The genteel manner of Mr. Joyboy brings to mind the comic funeral set piece in the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884). Peter Wilks’s funeral is a “skreeky” affair with a “long and tiresome” sermon. But it is the nameless undertaker who steals the show as he slides around “in his black gloves with his softy soothering ways.” Greeting the guests with undue attentiveness, he is a slimy character that Huck instinctively knows to be insincere: “he was the softest, glidingest, stealthiest man I ever see.” In a damning indictment, Huck concludes of the fellow, “there warn’t no more smile to him than there is to a ham.” While Huck famously fakes his own death, and later attends his own funeral, there is no such resurrection for poor old Peter Wilks. Dead means dead.

In 1960s America, however, that didn’t stop one from considering the everlasting. In The American Way of Death, Mitford is particularly tickled by an advertisement for “Futurama, the casket styled for the future….” Apart from its obvious gratuitousness — the inhabitant of the coffin is not going to be around to see what lies ahead — the casket idea is commercialization taken to the extreme.

We may think of this simply as quaint mid-century consumerism. But are we so different? Where Mitford lamented the rise of “singing telegrams” designed to comfort the family of the deceased, AI means we can now send curated messages from beyond the grave by way of interactive holograms. Today, one can blast one’s ashes into space for an interstellar send-off. Not to mention, cryogenic “burials” — perhaps the most cunningly futurama-banana ploy of all — which promise to resurrect the body by the year 3000 (or thereabouts).

As technology has advanced, it has brought our anxieties about death along for the ride. No one knows this better than Don DeLillo, the master of transforming modern America’s excessive consumerism into darkly comic death ballads. In White Noise (1985), an airborne toxic event slowly descends upon a tranquil college town, threatening to kill its inhabitants. This giant cloud resembles “a national promotion for death, a multimillion-dollar campaign backed by radio spots, heavy print and billboard, TV saturation.”

DeLillo wrote in White Noise that “all plots tend to move deathward.” But his 2016 novel Zero K attempts to reach beyond death itself toward eternal life. The story centers on a remote compound called the Convergence, where wealthy sponsors and investors hope to be cryogenically frozen by complex nanotechnology with a view to being reawakened in the distant future. “Why not just die?” the cult leaders ask, “Because we’re human and we cling … not to religious tradition but to the science of present and future.”

Such ideas about death were once relegated to the realm of dystopian science fiction. Now they are coming true. Maniac entrepreneurs like Bryan Johnson — in his own words, “the world’s most measured human” — are already spending millions to reduce their biological age. Perhaps our fate will not be to end up six feet under but to experience a weird half-life, sustained by the blood and plasma of younger relatives. America’s ruling political class, after all, are so geriatric one wonders if they too have got their hands on some death-defying tech. The new American way of death, it would seem, is not dying at all.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply