Dante travels through the circles of Hell, guided by Virgil. At the summit of the mountain of Purgatory, Virgil abandons him, leaving him with Beatrice, the woman Dante loved. With Beatrice’s smile, Dante is transported to Paradise, experiencing astral bliss as he soars through the cosmos. But Beatrice must leave him at the approach to the Eternal Fountain: for him to glimpse her smile further would be to incinerate him with its divinity.

The relationship between humanity and divinity lies at the heart of this new history of the Middle Ages. Mark Gregory Pegg’s vignettes of martyrs, theologians, scholastics and secular figures illustrate the development of Christianity in the West after the collapse of the Roman empire, and the making of Latin Christendom.

The period that Pegg covers begins in 203 and ends in 1431 — with two young women, Vibia Perpetua and Jeanne la Pucelle (Joan of Arc). Their commonality is their demise, martyrdom — Perpetua as a Christian and Joan as an accused heretic. Both women believed they were in direct communication with God. Perpetua’s divine visions were so powerful that she embraced her end in the cruel confines of the Roman amphitheater in Carthage “singing, indifferent to her nakedness,” welcoming it as she was gored by a bull before she helped the gladiator “slice her throat.” But there is no redemption in Pegg’s account of the Western transition from Rome to Christendom. Christians were hunted down and brutally murdered until the reverse happened, when paganism was branded as “impious and morally craven.”

A penitential culture that persisted from the seventh century onwards transformed how Christians believed they were judged by God, and Pegg traces the stories of those who lived in a perpetual state of remorse and atonement. A seventh century Syrian monk named Theodore regarded oral sex with ejaculation as “the worst of evils,” meriting “penance to the end of life.” In the fourteenth century, flagellants, or “flail-brothers,” whipped themselves “until the blood pooled around their feet.”

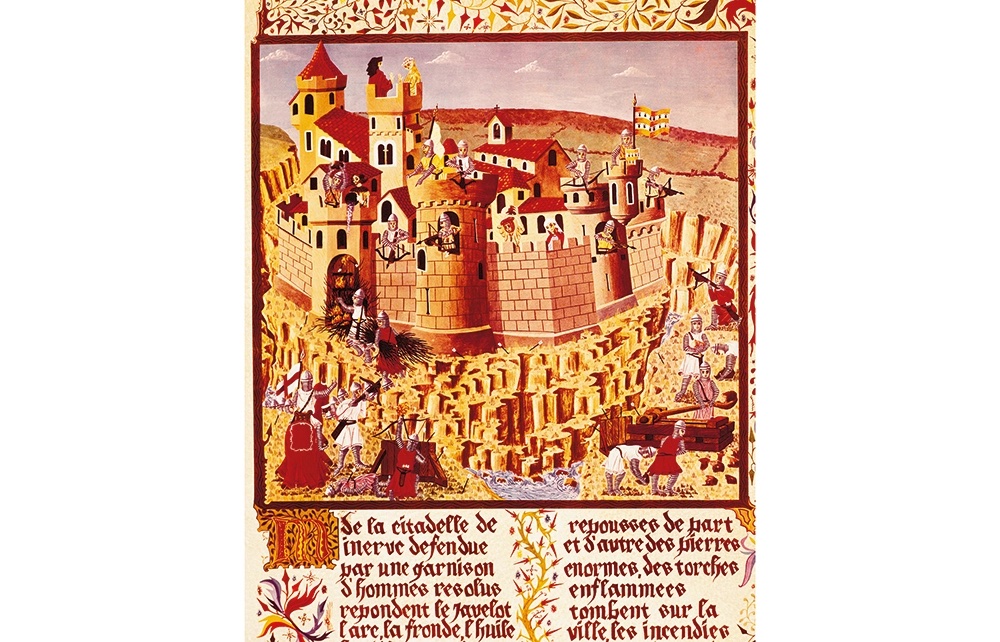

Jews were frequently on the receiving end of shattering inhumanity, as were those deemed heretics. In 1209, a “genocidal moment” erupted at Béziers in southern France — the first battle of the Albigensian Crusade. This saw 20,000 Provençal men, women and children put to the sword. These were the good people, writes Pegg, who “modern scholars erroneously call Cathars”:

After 1220… they became wandering refugees, barely clinging to memories of who they had once been in a world that no longer existed. The inquisitors had transformed these clandestine figures into a “heresy” by transforming them into a “religion,” or more correctly transfiguring them into a sect or an ecclesia, a church.

Over time, they came to perpetuate the identity forced on them by their oppressors.

Ending the story, Jeanne was also the victim of violent persecution as a heretic. Pegg notes, however, a distinct change since 203, since “Jeanne never actually thought she had achieved a sense of divinity.” By the fifteenth century “it was becoming harder and harder to imagine Christ and humanity as having any real compatibility.” What replaced this, following the Black Death, was the increasing Europeanization of Latin Christendom, when identity correlated with culture. Jeanne understood herself to be “first and foremost a Christian French woman.”

This narrative of the Middle Ages undertakes the monumental task of chronicling an extensive period of time with, inevitably, numerous characters and fluctuations. Pegg gives little explanation of why he chose to begin his history in 203, and the relationship between the human experience and the divine — which is the connection to Dante’s pilgrimage from the outset — sometimes gets lost. Without a gloss on complex terms, readers outside the academic sphere are in danger of finding themselves confused or alienated from what is a gripping story.

Beatrice’s Last Smile is undeniably well-researched. Pegg includes often marginalized groups, such as women and Jews, and the chapters on the later Middle Ages from the Albigensian Crusade to the Black Death are a particular highlight. His examination of the almost global spread of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that caused the plague, shows his skill as a medieval historian in handling the various sources. With a few more authorial markers in place, and awareness of the limitations of the general reader, Beatrice’s Last Smile could serve as a fine example of the scope of narrative history.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.