Generalizations about national characteristics are open to question. Nevertheless, the overwhelming impression one gets from reading the major works of English literature, or from studying the famous English men and women of politics, the military or the academic world, is that the English have not been an especially religious lot. Or, if you think that a strange judgment of a nation that produced the finest Gothic cathedrals in Europe and the hymns of Charles Wesley, then you could rephrase it and say that they have not generally worn their religious feelings on their sleeve. Jane Austen’s hilarious novels do not quite prepare us for her letters in which she confesses her sympathy for evangelicalism. The novels are not only wonderful; they seem the quintessence of what we would like to think of as English.

Shakespeare describes almost all the emotions except the religious. Isabella in Measure for Measure is almost the only overtly religious character in the entire oeuvre. Dickens was in favor of Christmas and being kind, but his Life of Christ is really a bit of secular sentimentalism.

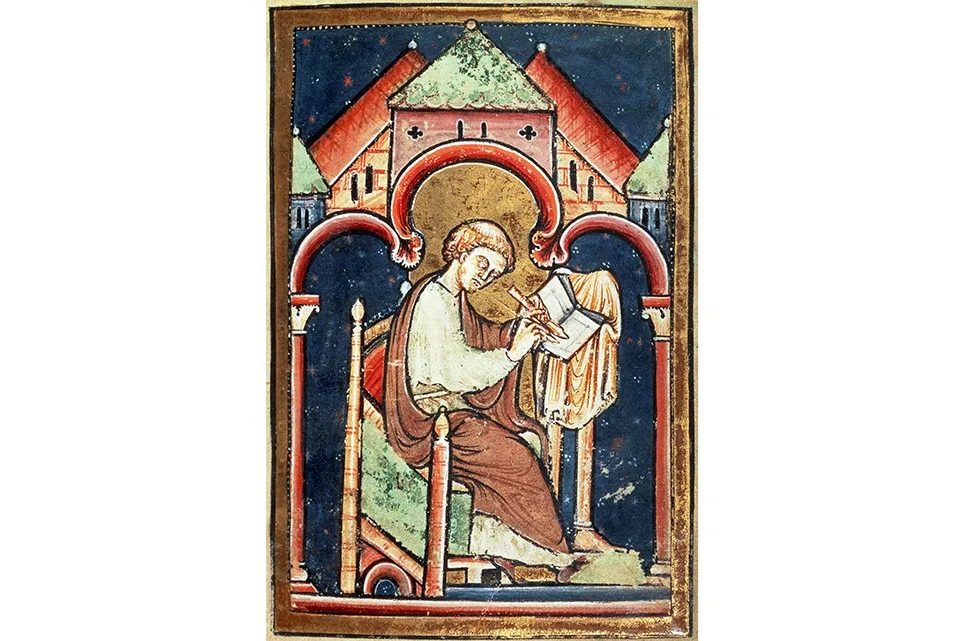

Undeterred, Peter Ackroyd has undertaken to tell the story of the English soul. Inevitably, therefore, it omits Shakespeare and John Locke and Dickens and William Cobbett. It is not a continuous narrative but a series of thumbnail sketches of some of the figures in English religious history, starting with the Venerable Bede, taking us on a breezy tour of the medieval mystics Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, and whizzing through the cast list of Archbishop Laud, George Fox, John Bunyan and Cardinal Newman before we reach the twentieth century.

Ackroyd wrote a brilliant book about T.S. Eliot, whose Four Quartets were written when that austere American had become not merely a British citizen but a self-confessed monarchist and Anglo-Catholic. Surprisingly, neither Eliot nor his Christian witness get a mention. There is a chapter on C.S. Lewis and G.K. Chesterton, preceded, in an odd chronological twist, by Richard Dawkins. And then we round off the story with three theologians: Bishop John Robinson, of Honest to God fame, John Hick and Don Cupitt. None of them, surely, is of sufficient merit or weight to be placed in a book with Richard Rolle or William Blake. And where is that great English churchman Dr. Johnson?

Ackroyd’s novels — especially English Music, The House of Doctor Dee (perhaps his masterpiece) and his bizarre fantasy Milton in America, in which he transports the author of Paradise Lost to the colonies — are true evocations of the English soul. They also retain what is, or was, a huge part of Ackroyd’s personality when he was out and about in London, before retreating into his anchorite’s cell near Harvey Nicks — namely, humor. His biography of Thomas More is the best. His book on William Blake is completely wonderful.

It is in the context of contemplating Ackroyd’s near genius in these earlier books that I dare to express a bit of disappointment in this one. In the acknowledgements, he thanks research assistants, and, although I am sure they have done their best, there isn’t much in The English Soul that you could not get from clicking in and out of the relevant Wikipedia entries on Wesley or the Diggers. In fact, because the book jerks hastily from one subject to another, it feels more like the experience of looking up names in Wikipedia than like reading a book.

Before Ackroyd wrote his novels, he was also a poet, and it was with a poet’s skill that he evoked, in his fiction, the spiritually bizarre. How glorious it would be if he regarded the sketches which make up this book as work in progress towards his own Four Quartets.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply