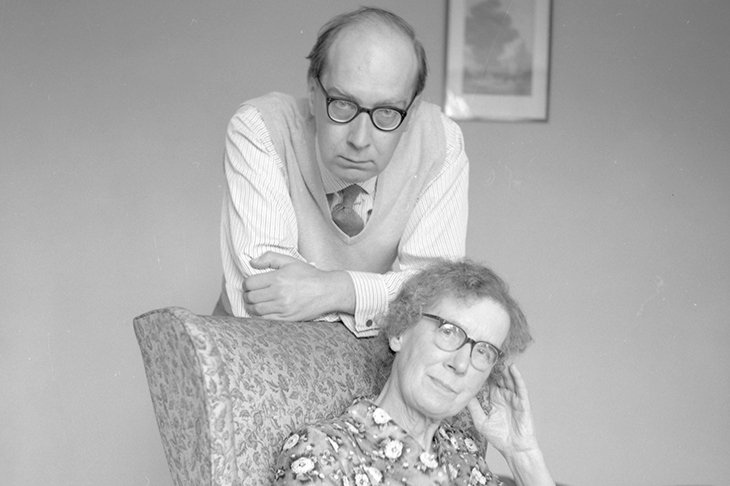

On 13 September 1964, at the age of 42, Philip Larkin began writing to his mother Eva (his ‘very dear old creature’) by taking stock:

Once again I am sitting in my bedroom in a patch of sunlight, embarking on my weekly task of ‘writing home’. I suppose I have been doing this now for 24 years! on and off, you know: well, I am happy to be able to do so, and I only hope my effusions are of some interest to you on all the different Monday mornings when they have arrived.

A great deal of what is characteristic about Letters Home is evident here. The sense of taking part in a ritual (‘Once again’); the pleasure in fulfilling a filial duty (‘happy to be able to do so’); the acknowledgement that it’s a bit of a chore (‘embarking on my weekly task’); the faint self-mockery (‘effusions’); and the air of being engaged in a performance (‘I am sitting in my bedroom in a patch of sunlight’).

These things aren’t in themselves remarkable, but what is astonishing is that Larkin maintained the balances of his ‘task’ for such a long time, and with such devotion. We learn from James Booth’s introduction to his selection from the correspondence that it falls into two main groups. One contains a little less than 100 letters and cards belonging to the period between Larkin’s departure from his home in Coventry to study in Oxford in 1940, and the death of his father in 1948. The second covers the period between his arrival to work in the library at Queen’s, Belfast in 1950, and his mother’s death aged 91 in 1977. For the first 22 years of this latter period Larkin wrote a letter to Eva every Sunday, and a card and/or another letter mid-week; for the last five years of her life, when her mind had wandered, he dropped her a line most days, and sometimes twice a day.

When Anthony Thwaite published Larkin’s Selected Letters in 1992, he baulked at the size of the correspondence with Eva and decided not to include any of it. When I published my biography of Larkin in 1993, I had space to quote only from a sufficient number of the letters to give a clear sense of the relationship they express. This means that Booth’s edition offers the first panoramic view of the correspondence, and even this is (necessarily) incomplete. By his own account, some 4,000 of Larkin’s letters and cards to his mother survive from the period 1936–1977. He has chosen 607 of them, adding a handful of the surviving replies from both parents, and also a small number of the few surviving letters to Larkin’s sister Kitty.

The good news is, Booth is an efficient editor and provider of footnotes: this is the last significant collection of papers relating to Larkin’s life that needs to be published. In addition, the sheer scale of the correspondence reminds us that Larkin — although curmudgeonly (and worse) in all sorts of ways — was also capable of great kindness. Whatever else the letters demonstrate, they embody (with a few exceptions) a remarkably sustained show of devotion, for which Eva was clearly grateful.

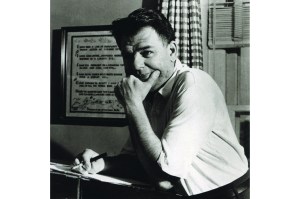

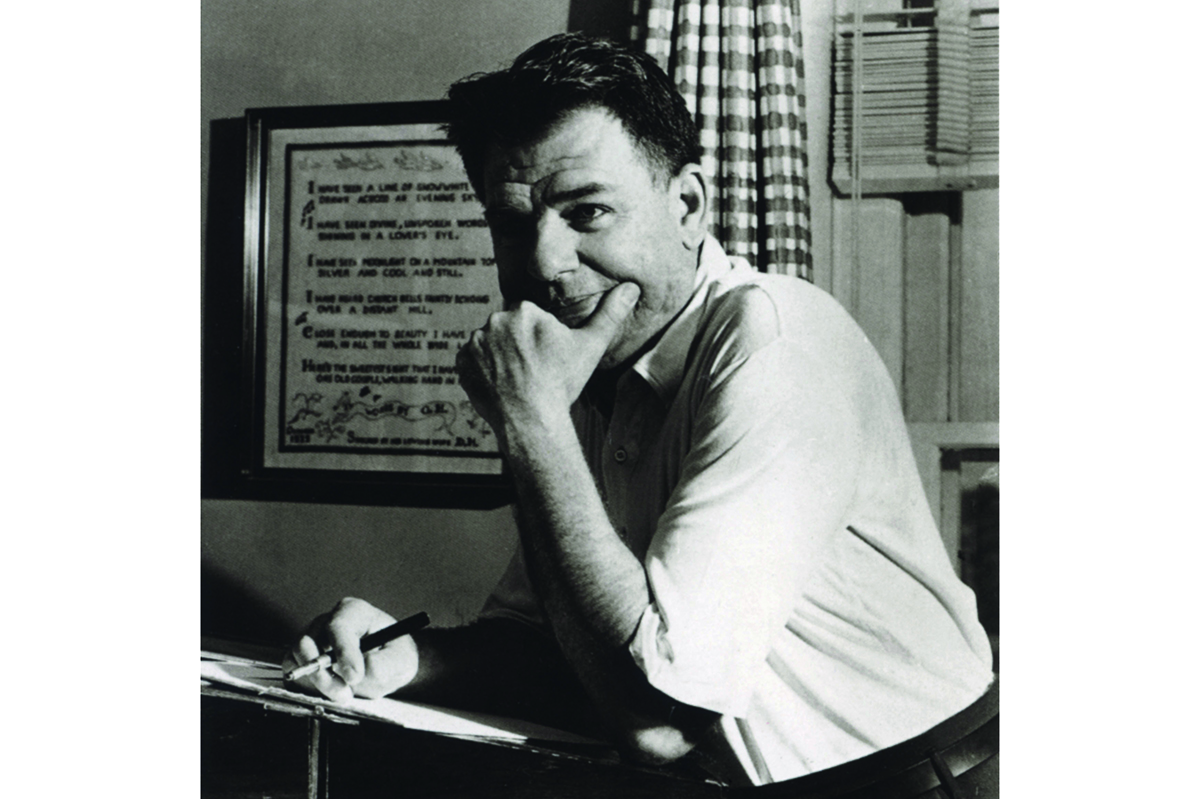

And of course there are other ways to value the letters as well. There are a few good brief portraits of interesting figures: Dylan Thomas (‘He wore two sailor’s jerseys, a shabby purple-yellow checked sports coat, and speckled grey trousers’); E. M. Forster (‘A toothy little aged Billy Bunter’); Betjeman (‘he seemed a rather humble and crushed creature’). There are Larkin’s usually amusing cartoons, which show him and his mother as ‘creatures’ at once shapeless and distinctly affectionate. And there are a few flashes of appealing descriptive writing (at Oxford, for instance when he tells his sister ‘gusts of snow blow past Big Tom and away into the Meadows, where are no footprints’ — then follows up with characteristic undercut by adding: ‘Tell me if you like [this]. It’s quite easy’).

The less good news is that the vast mass of the letters’ content is humdrum or trivial — because it speaks so exactly to the minute particulars of Eva’s life, and to similar elements in his own day-to-day existence. Booth in his introduction tries to persuade us that Larkin spoke to Eva with an openness unusual in mother-son relations, when he talked to her as a student about Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Maybe so, maybe not. And anyway, such forthright moments are very few and far between, as Larkin himself suggests when he writes to her in June 1945 and says ‘I hate laying myself open — I hate being prodded and turned over and pinched like fish on a slab.’ He’s writing about job applications when he says this, but the same principle applies on the home front.

He says next to nothing about the other important relationships in his life (Kingsley Amis, Monica Jones, Maeve Brennan), nothing about his poems beyond a few obvious indications of sources, and nothing of interest about books he is reading, or ideas he is entertaining. Instead, we get: ‘My inside feels a trifle congested at the moment, for I have eaten nearly a whole tin of salmon for supper, & nearly a whole tin of asparagus.’ And:

I didn’t shop very carefully yesterday, & forgot bananas (I eat these regularly now — they are easy things to manage) and have no caster sugar for my grapefruit. I might find some bananas today, but the sugar will have to wait.

Even a little of this sort of thing goes a very long way for the general reader, no matter how warmly it was meant and received. Moreover, the cumulative effect is not just dull, but likely to provoke thoughts that clash with the charity on show. Larkin was generous to write to Eva as much he did, no doubt about it. But he almost always did so in ways that allowed him to keep himself to himself — and only to express strong opinions when he knew they would not cause his mother to disagree. Including, presumably, the racist opinions which are dotted through the book, and which Booth ineffectually tries to dim by reminding us they do not represent the whole of Larkin’s social response. When Larkin tells Eva in May 1970 that ‘Mr [Enoch] Powell is still saying we must keep out the immigrants — a pity he isn’t leading the Conservatives’, he gives a clear view of the attitude that lies beneath and informs everything.

In other words, the correspondence is a form of control as well as charity. It was also a form of attachment he at once cherished and resented. He admitted as much, in another unusual flash of candour, in a letter written in April 1970 in the aftermath of a visit he has paid to Eva:

I’m afraid I was not a very nice creature when at home. I wish I could explain the very real rage & irritation I feel: probably only a psychiatrist could do so. It may be something to do with never having got away from home. Or it may be my concern for you & blame for not doing more for you cloaking itself in anger.

What we glimpse here is the ‘violence a long way back’ that Larkin mentions in his ferocious late poem ‘Love Again’ — violence compounded of his father’s right-wing severities, and his mother’s adhesive dependency. And although, due partly to his father’s early death, he was able to moderate if not entirely dispel the influence from that quarter, he was to some extent under his mother’s spell for most of his life. In some ways — as his correspondence with others amply reveals — it suffocated and depressed him. In other ways it suited him fine. He could play Eva’s need of him against the demands that other women might otherwise make to takeover his life.

And as far as his poems were concerned, Eva in all sorts of unlikely ways acted as his muse. Her preoccupation with trivialities was transformed by Larkin into a rare poetic appreciation of the everyday. Her long and slowly failing life, with all its accumulating fears, kept his concentration fixed on the central theme of his work: ‘Age, and then the only end of age.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.