At the Villa Pignatelli in Naples there is an exhibition by Elisa Sighicelli: photographs of bits and pieces of antiquity from, among other places, the city’s Archaeological Museum. Put like that it doesn’t sound so interesting but the results are stunning.

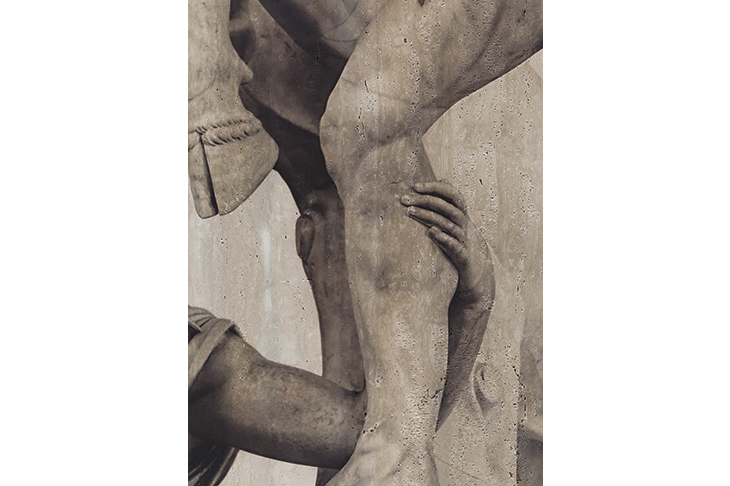

Walking through the Archaeological Museum after seeing the exhibition it was difficult to discover the original objects from which Sighicelli’s samples were taken. One instance, a tight crop of fingers pressing into a calf, is from a highly elaborate, much restored and augmented sculpture with so much going on — a naked swirl of bodies, a rearing horse, a sympathetic doggy — it’s hard to imagine how she found it in the first place. From the midst of this limby extravaganza the resulting image is as tactile as a close-up of a physical therapist massaging the muscled calf of an injured soccer player.

Even when you have located the original it is tricky, sometimes, to work out how the picture might have been coaxed from it. Taking the photograph must have involved a kind of archaeological excavation in its own right: a kind of visual dig. The original works are not just photographed but transformed. Tightly framed, the goddess Aphrodite’s midriff and hip have a slinky stillness — a form of naked display enhanced by concealing folds of stone drapery — that embodies the erotic force of millennia.

These images are printed on the same materials from which the original objects are made — marble, travertine — so that there is a symbiosis between what is depicted and the way it is shown. We associate photography with the moment but the main feeling induced by these entirely flat images is of temporal and sculptural depth, of deep permanence. The photographs simultaneously remove the object from and return it to its source. The new stone becomes imprinted with an achieved vision of itself, of what it had become. (It’s like a version, in a way, of that miraculously faked relic, the Turin Shroud.) The veins in the marble remind us that the statues are themselves idealized renderings of what might be called the ultimate original, without which there would never have been any art (or gods, for that matter, if you are of a Nietzschean bent): the veiny human body. Blotches in the processing or flaws in the marble are symptomatic of the defects and wounds to which the flesh will always be heir — including the flesh of gods.

Photography is all about surface — ‘the surface is all you’ve got’, as Richard Avedon insisted. Looking at the two muscular male torsos of the Tirannicidi, however, it’s impossible not to think of how the ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo’ scrutinized by Rilke was ‘still suffused with brilliance from inside’. And whereas Christianity brought about an agonized separation of the spirt from the body, here there is a powerful affirmation that the spirit dwells in — is part of —the flesh. With their combination of purity and sensual power, these isolated body parts kept bringing me back to Jack Kerouac’s observation about Neal Cassady, the model for Dean Moriarty in On the Road: ‘A man who can sweat fantastically for the flesh is also capable of sweating fantastically for the spirit.’

The following day I went to the Museo Cappella Sansevero to see Giuseppi Sanmartino’s sculpture of the ‘Veiled Christ’ (1753). It’s justly famous for the way that hard marble has been transformed so that we see the dead Christ, stretched out on a tomb, through a diaphanous veil of the thinnest fabric. The almost-immaterial has rarely been better achieved by stone. And yet, great though it obviously is, I found myself wondering, blasphemously, if the trompe-l’oeil quality of see-through stone might not be slightly stronger in the numerous photographs of the work that had made me want to come and see it.

Downstairs, the two so-called ‘anatomical machines’ from the 1760s are the opposite of veiled. Housed in glass cases these ‘machines’ consist of the upright skeletons of a man and a woman with their arteriovenous systems preserved almost intact. So intricate is the web of large and tiny veins that, from a distance, it looks like the skeletons have donned ghastly, close-fitting fur coats in an attempt to preserve a measure of modesty in the face of the chill stare of eternity. Up close they are laid bare by what appears to cover them. So they stand there, these two specimens, simultaneously the flayed descendants of Adam and Eve, and the rather shabby, mid-18th century ancestors of the slick exhibits in Gunther von Hagens’s plastinated Body Worlds.

It was a relief to leave this weird stuff behind, to get outside and back in the world of heat and flesh, of melting ice cream and skimpy clothes. From the Cappella Sansevero I walked, a little self-consciously, through the tight streets and hanging laundry of the Spanish Quarter. I’d been here twice before, many years ago, and on both occasions considerate old ladies had warned me that it wasn’t safe. Was it really dangerous or a place where people were unusually concerned with one’s safety and wellbeing? Possibly both. This time, keeping hands in pockets and phone in hand, I was left to my own devices. It was twilight, there were no signs of gentrification but there were plenty of signs of everything else. Lighted street shrines — dedicated to the Virgin, to various saints — had the beauty of magic that has endured so long as to be perfectly ordinary.

And then, quite by accident, I came across exactly what I had hoped to find. On the wall of an apartment building was a huge gray mural of what looked, from a distance, like the ‘Veiled Christ’, in slightly androgynous mode. Getting closer I saw that it was a version of another of these ‘veiled’ sculptures from the same church, of a woman this time, by Antonio Corradini. In Manhattan this would have been an advert for underwear or for a highly sexualized perfume called Spirit or some such. Here it formed part of a tacit diptych, the other half consisting of a slightly smaller mural, on a nearby wall, of Diego Maradona (to whom a shrine was dedicated beneath the veiled woman). Now, I don’t have a spiritual bone in my body, obviously, but I sensed immediately that I was in close proximity to the thing I crave, the main incentive — stronger than the lure of art or the possibility of sexual adventure — for going anywhere: the experience of religious power converging on and emanating from a place.

Maradona is not just one of the greatest footballers of all time. Asif Kapadia’s recent documentary tells the story of what happened after Maradona signed for Napoli in 1984 for what was then a world-record transfer fee: how he led the team to their first ever Serie A title in 1986–7, followed by a second two years later. And then? First, betrayal — essential in any Catholic drama — in the form of the penalty he scored for his national team, Argentina, in the 1990 World Cup, against Italy, in the very stadium in Naples where he was worshipped. Second, he fell foul of the Camorra crime syndicate who had helped feed and satisfy an increasing hunger for hookers and, more disastrously for an athlete, cocaine. Footage from the end of the film suggests that Martin Amis was right: ‘Inside every fat man, they say, there is a thin man trying to get out. In the case of Maradona, it seems, there is an even fatter man trying to get in.’

Maradona’s tragicomic story is long and ongoing but the essential thing about his time in Naples can be stated very simply: in this city a boy who had grown up in the slums of Buenos Aires, who had already risen to heights of unimaginable greatness, became a God. That is a subject worthy of a book by Roberto Calasso but it is, I suspect, unfilmable. Still, the evidence here, at this shrine, is persuasive. A team of pilgrims, all kitted out in Maradona’s blue number 10 shirt, came and photographed each other beneath the mural. I took some pictures of them too, with my phone. I wanted to have a permanent record of this fun scene, this sacred site — or a few visual relics, at least.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.