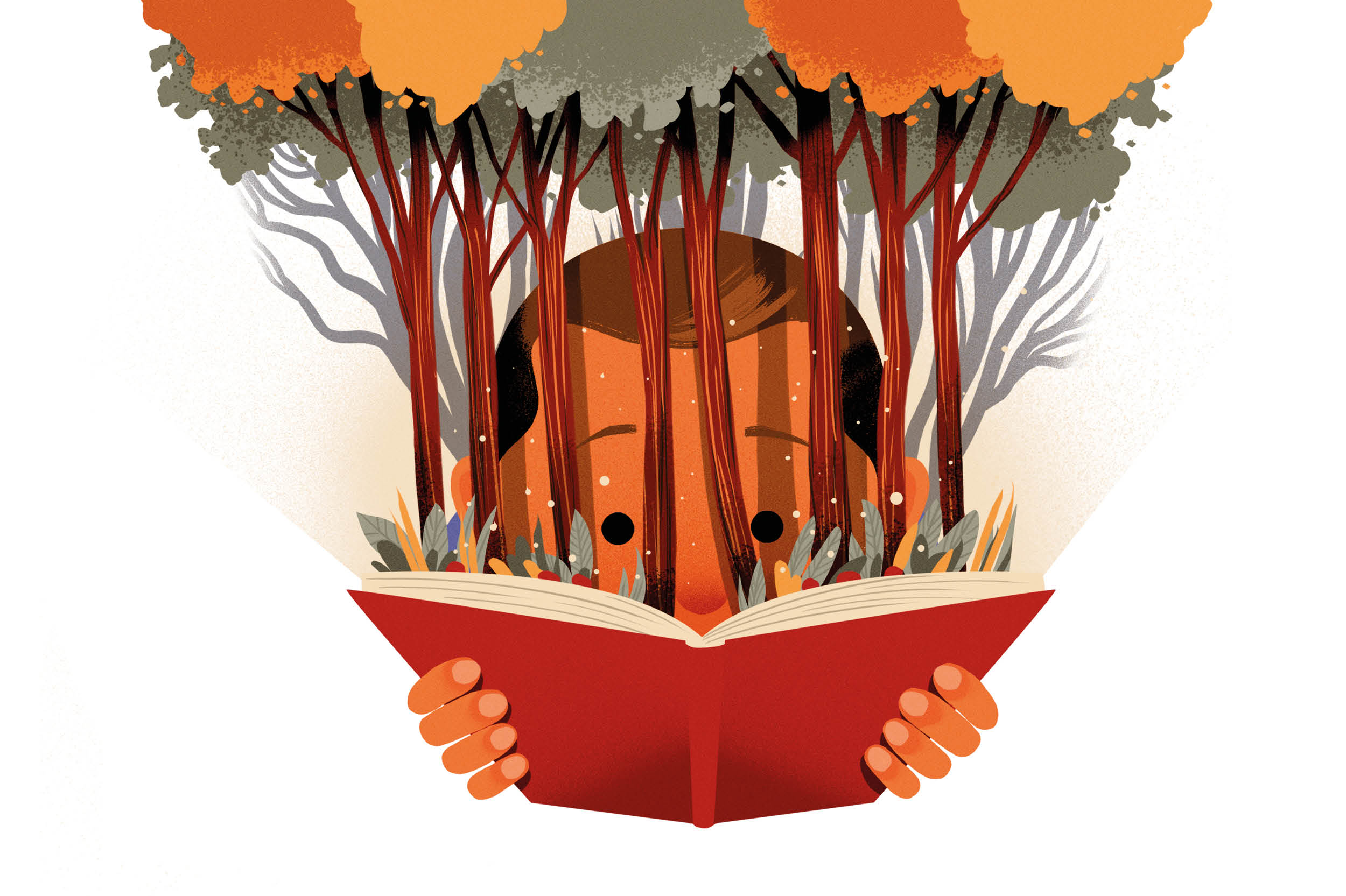

Readers familiar with Sheila Heti’s work, most notably How Should a Person Be? and Motherhood, in which she examines both the possibility and implications of choosing one’s life and dealing with the consequences, will be familiar with her apparent capriciousness. Her prose — freewheeling, elliptical, a tangle of jokiness and jeopardy — seems to capture the puzzle of proportionality: how seriously should we take this one life we have, and how can we hope to balance our opposing urges towards levity and gravity?

In Pure Colour, we appear to be in similar territory, immediately introduced to a playful version of the universe in which humans are the critics of God’s artistic creation and divided into three categories: birds (concerned with abstract ideals such as beauty and harmony); fish (focused on the greatest happiness of the greatest number) and bears (who devote their emotional intensity to those they love the most).

What we perhaps haven’t cottoned on to, the novel’s third-person narrator suggests, is the idea that we are merely God’s initial go at this — “expendable soldiers in the first draft of the world” — and that future beings might be freed from an awful lot of the troublesome mental and psychological baggage that makes our lives so difficult. The question of what purpose art would serve in this imaginary theological scenario pushes itself forward. What if art is necessary only for our particular situation, and intractably connected to our most destructive impulses, our addiction to “killing and winning”? Would it be so bad if all that were gone, even if it meant that art were lost too?

It’s hard to describe Heti’s ruminations without making Pure Colour sound like a dreaded thought experiment. But the novel is drenched in feeling, most of which attaches itself to Mira, whom we first meet when she is a pre-internet, pre-modern student bumming around with her pals, all of them “fine with living our mediocre lives. It didn’t occur to anyone that we could have great ones. That was for people far away.”

Mira falls in love with a woman called Annie; she works in a lamp shop; she lives in terrible apartments; she has no obvious plan for her future — standard stuff, described with an ironized glibness. But as she ages, and specifically when her father dies, a sense of loss and grief begins to suffuse the writing, filling it with an earnest austerity that at times makes it feel like a piece of devotional writing that has more in common with a medieval or metaphysical sensibility than with the contemporary.

Heti has spoken about how her own father’s death during the writing of the book changed its character completely, and it’s true that there is a disjointed feel to it. Much of it is written in fragments and vignettes, but the sections that deal most directly with bereavement, and with the loss of a foundational figure, make it clear that this is entirely apposite: that the erasing quality of grief, its ability to shatter what has gone before and make even the thought of a moment beyond itself wildly improbable, can only be written like this. All the particularities — sadness, regret, guilt — are part of the greater reconfiguration of the world.

‘Feces, worms, piss, trouble. This is where we are now. Our dressing up has led us nowhere; our manners have led us nowhere.’ These are, in fact, Mira’s reactions to romantic disappointment, long before she has to contend with a very different order of loss. But this strange, affecting novel, whose precarious structure is such a part of what it is trying to convey, has much to say about the feelings that are with us throughout our lives, waiting for their moment to strike.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.