But why did she marry him? That is the question so often asked of heiresses who have, it would appear, the chance to marry anyone on whom their fancy alights yet so often make bad choices. And it’s the question reverberating through this funny, insightful and extremely modern look at an age-old problem by the British author Laura Thompson.

“Why, when one had the power of near-limitless choice, would one choose so badly?” she asks. Taking this as her challenge, she examines dozens of (mostly ghastly) marriages over the last four centuries before concluding that it was a rare heiress who triumphed over her ordained fate as a victim, but it was indeed possible.

Such latter-day inheritors of their forebears’ vast wealth as Barbara Hutton, the Woolworth heiress who married seven times, and Christina Onassis, the shipping heiress who died aged thirty-seven, give flesh to the myth of the unhappy Million Dollar baby, born with limitless material advantages yet unable to buy love, the thing they most craved. Yet was their unhappiness inevitable because they saw their own lives in this tragic way?

This brilliantly entertaining survey starts in seventeenth-century Britain with little Mary Davies, the twelve-year-old heiress who owned some of the most valuable land in the world (which eventually became the Westminster Estate), and continues into the twentieth century, with several so-called Dollar Princesses in the middle. The latter were rich and often beautiful (or “snappy,” the contemporary term for sexy) American girls used by their mothers to trade cash for titles, girls like Consuelo Vanderbilt, who became the famously unhappy Duchess of Marlborough, and her predecessor, Jennie Jerome, who had neither dollars nor aristocratic lineage, but became Lady Randolph Churchill, the mother of Winston.

Thompson shows how until the Married Women’s Property Act of the late nineteenth century — in America, this progressive legislation happened slightly earlier — once a woman married, her husband took possession of almost everything, making every man a risk to an heiress and every rich American woman deeply attractive as a source of shoring up a crumbling country pile. Some men behaved so badly that wasting their wives’ money became something of an obscure act of revenge against her for having so much of it. One obvious solution for a rich woman was to stay single, since a spinster had the same property rights as a man. Marrying an equally rich, unattractive man and taking lovers was another option, since being married gave women status in a way nothing else could. Anything approximating work or getting a job was, of course, impossible. So these vulnerable heiresses had to learn to manage the risk.

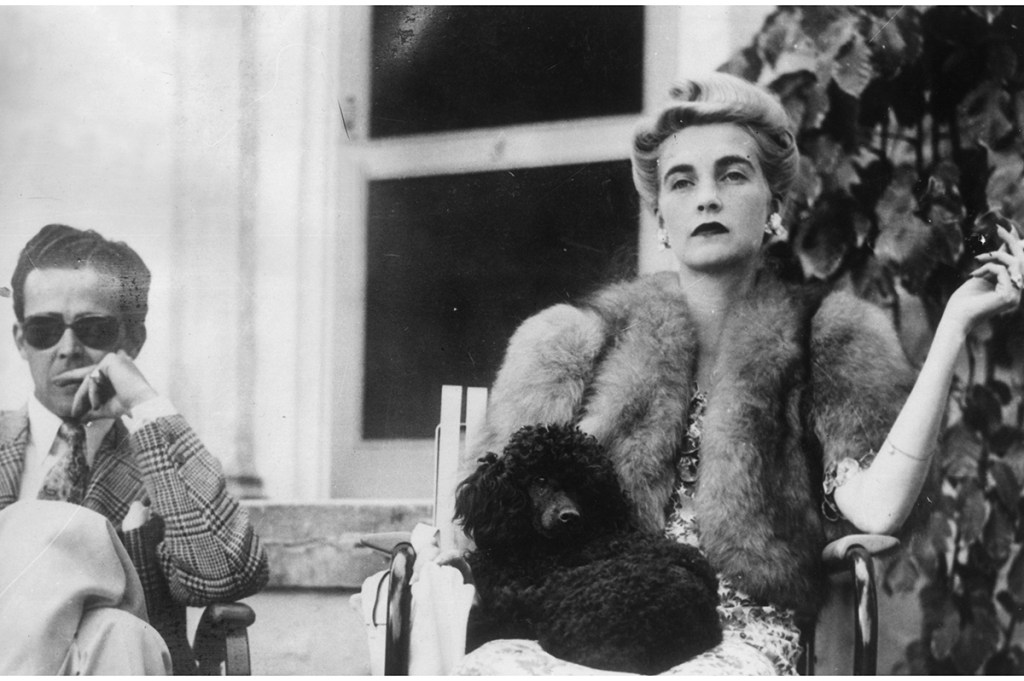

I felt rather exhausted following all these women living life in the fast lane, and almost overwhelmed by their stamina, their excesses, their fabulous jewels and their monied sexiness. Couldn’t they just occasionally have settled for a little less of everything? At Deauville in the summer of 1921, the philandering politician Duff Cooper, married to the exquisite Lady Diana Cooper, felt intoxicated by his current affair with the heiress Daisy Fellowes — daughter of a duke, widow of a prince, and recently married to the Hon. Reginald Fellowes. Duff observed how opium lowered his lover’s inclinations for their afternoon trysts to absolute zero, and once returned in the evening for more. His long-suffering wife Diana called the police and pretended to worry that her husband had been murdered.

It was a dramatic revenge that did not end the affair but added one more rollicking story to the hundreds already swirling around this “turbo-charged” heiress. Daisy remained married to the unexciting if amiable Reginald until his death in 1953. She had probably married him so that she could carry on with her reckless, adulterous, drug-crazed life full of parties, yachts, lovers and dress fittings. She died in 1962 in Paris with just over $100,000 remaining from the fortune she had inherited from her grandfather, the sewing machine millionaire Isaac Singer, her heart apparently weakened by grief and hedonism.

And yet this is only one version of the story. Thompson argues that while Daisy can be seen as the typical poor little rich girl, in her case “über-rich” — über is a favorite word in this story of excess — with a mother who committed suicide and a father who never found happiness, her life can equally be seen as something that she controlled. After all, she used her inheritance to gratify huge appetites, whether her own or others. Thompson wants us to believe that Daisy was a rare kind of heiress who indulged an uncomplicated desire to enjoy her money, but at least had freedom over how she spent it.

However, most of these heiresses were weighed down by their cash. With Alice de Janzé, the beautiful Buffalo-born American heiress who famously commented on waking in Kenya’s Happy Valley, “Oh God, not another fucking beautiful day,” the question as to why she married the men she did moves into psychodrama. In 1926, wed to the French count Frédéric de Janzé and mother of two children, she fell passionately in love with a young Englishman called Raymond de Trafford. But he did not want to marry her. In 1927, at a farewell lunch to mark the end of their affair, she produced a gun and shot him before turning it on herself. But both survived and she had to face a trial where she was let off with a fine. Four years later, they married after all. Unsurprisingly, the union did not last, and Alice, now troubled physically with abdominal pain as well as emotionally, finally killed herself in 1941 with a bullet through her heart.

After this, the life of Barbara Hutton might seem rather tame. She had had the good fortune to count the handsome film star Cary Grant as the third (and kindest) of her seven husbands, and, during World War Two, she performed notable good deeds. These included giving money to the Red Cross and the Free French; after the war, she donated Winfield House, her magnificent home in London’s Regent’s Park, to the US government. Yet she was ravaged by constant dieting and at the end weighed little more than her jewelry, which was, admittedly, rather a lot.

The book is studded with wit, and Thompson has a neat way with one-liners. She says of the nineteenth century, “it makes one long to reach back in time and hiss dire warnings” and remarks that a childless great-uncle was “one’s favorite kind of great-uncle.” She is especially good at linking the stories to contemporary literature: after all, the relationship between a woman and her money inspired novelists from Jane Austen to Edith Wharton, although real life was often much stranger than their fiction.

Just as it seems as if this rollicking pace is about to calm down with an epilogue about an ostensibly sensible English woman, Angela Burdett-Coutts, “who had a will as unyielding as whalebone in her corsets,” she too shocks us. We expect to meet a female inheritor who will redress the balance of the often-unedifying spectacle of greed and waste that has gone before by becoming a philanthropist who deliberately did not marry. Burdett-Coutts joined forces with Charles Dickens, and together they founded Urania Cottage, a home for fallen women. She also built housing for the poor in London’s East End and became deeply involved in animal welfare.

Then, in 1880, aged sixty-six, she married one of her secretaries, William Ashmead Bartlett, an impecunious American former actor almost forty years younger than her. A shocked Queen Victoria commented “Lady Burdett really must be crazy.” She duly forfeited three-fifths of her income because of Bartlett’s foreign birth. Nonetheless, they remained wed until her death in 1906.

One thing many of these heiresses shared was an indifference to public opinion. Not only were they unhappy; they were publicly unhappy. But Thompson, who refreshingly writes that she thinks an apartment on the Upper East Side, a Stubbs painting, fittings at Givenchy and all the rest just might make her happy, concludes that money could not provide happiness for heiresses because they had never known a time without it. Only if they had had to earn it could these women have understood the value of what they had never been without.

A bit of longing is apparently good for us.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2022 World edition.