Those who conduct the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra may not be aware that musicians fill in a form after they leave marking them out of 10, sometimes with an acerbic comment on their performance. Industrial democracy is alive and well in the West Midlands, along with a Red Robbo urge to biff the bosses, as Richard Bratby’s centennial history of the CBSO entertainingly reveals.

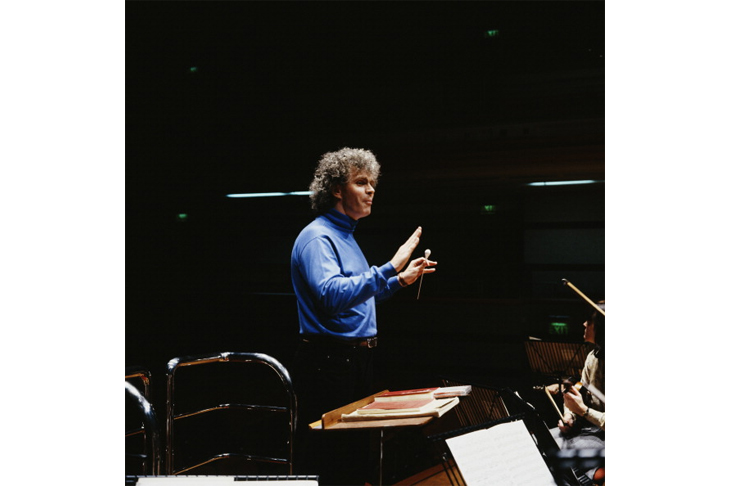

Democracy can foster great leaders and, in this sphere, the CBSO is the envy of the world. Three of its last four chief conductors, chosen by the players, have gone on to the highest peaks — Simon Rattle to the Berlin Philharmonic, Andris Nelsons to Boston and Leipzig, and Mirga Grazinyte-Tyla to the forefront of a new wave of women conductors who are wresting the baton away from male grip.

If Rattle’s successor, Sakari Oramo, proved less explosive, it may be that he reflected an alternative streak in the orchestra’s character, a quirky appetite for Nordic and English eccentrics. Be that as it may, no nation state in modern times has chosen great leaders so unerringly well as the CBSO.

Birmingham kick-started an orchestra after Edward Elgar grumbled for several years that the heart of England lacked a musical engine. Founded in 1920 with Appleby Matthews as first conductor, the CBSO was shaped by Adrian Boult, who left in 1930 to head the BBC’s new symphony orchestra.

Leslie Heward and George Weldon looked after the 1930s and 1940s; Rudolf Schwarz promoted English composers in the 1950s; there was a gentle interregnum with the Polish exile Andrzej Panufnik, followed by a decade of Hugo Rignold. A French affaire with Louis Frémaux ended when a players’ rebellion got the manager sacked by the board. Frémaux, who had fought in the Resistance, was appalled at the disloyalty and never returned.

Up to this point it is fair to say, though Bratby avoids saying it, that the CBSO was hardly ever at the forefront of national attention — apart from the great occasion in May 1962 when Rignold led the world premiere of Britten’s War Requiem in the rebuilt Coventry Cathedral. Otherwise, in concert and on record, Britain’s swagger bands were the London orchestras, John Barbirolli’s Hallé and the Liverpool Phil, breeding a state of resentment in Brum.

All that changed in 1978 when a young Liverpudlian called Ed Smith was hired as manager, bringing with him a chap of 24 whom the musicians liked pretty much on sight. Simon Rattle’s 18 years are reported by Bratby through the prism of ten signature works — among them Pierre Boulez’s Rituel, Mark-Anthony Turnage’s Three Screaming Popes and Thomas Adès’s Asyla — works that defined their era musically for all time to come. Away from music making, Smith and Rattle (don’t they just sound like Peaky Blinders?) went in, guns blazing, to the Arts Council and the EU, coming away with enough dosh to build the best-sounding Symphony Hall in Europe, bar none.

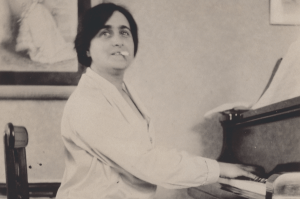

If Oramo turned the clock back to marginal composers such as John Foulds and Arnold Bax, as a former violinist he attended particularly to polishing up the string sound, which was not always Rattle’s forte. The next two maestros were picked by acclamation. Nelsons, a young Latvian, arrived to conduct an acoustic test at the refurbished town hall. Before the session was over, players were sending texts to their manager to sign him right away. A similar apotheosis was felt with the even younger Mirga who, given a Sleeping Beauty suite at the fag-end of the concert season, had the players practically dancing in their seats. Footwork aside, Mirga likes to sing madrigals with her musicians a capella in her dressing room after a particularly taxing performance.

Bratby, The Spectator’s music critic, brings an insider’s eye to these excitements. A well-traveled orchestral cellist who served as manager of the CBSO Centre, he takes a backstage perspective, at times the slightly jaundiced view of underpaid musicians and undervalued staff. While never quite giving marks out of 10, he leaves readers in no doubt which conductors did best to improve tonal quality and social engagement with a city of bewildering diversification.

Unlike other orchestra histories which focus on strategy, money and boardroom crises, Bratby assures us in his opening pages that

‘unless stated otherwise, it should be assumed that at any given point in this history the orchestra is either barely breaking even or is facing a worrying financial shortfall. This is also likely to apply for the foreseeable future.’

That a symphony orchestra can survive at all in blunt-spoken Birmingham is a minor miracle. That it can thrive and shine under this slip of a Mirga is a source of wonderment to all. How it is achieved is the history that Bratby tells, and tells so well. Prepare to be amazed.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.