This article is in

The Spectator’s November 2019 US edition. Subscribe here.

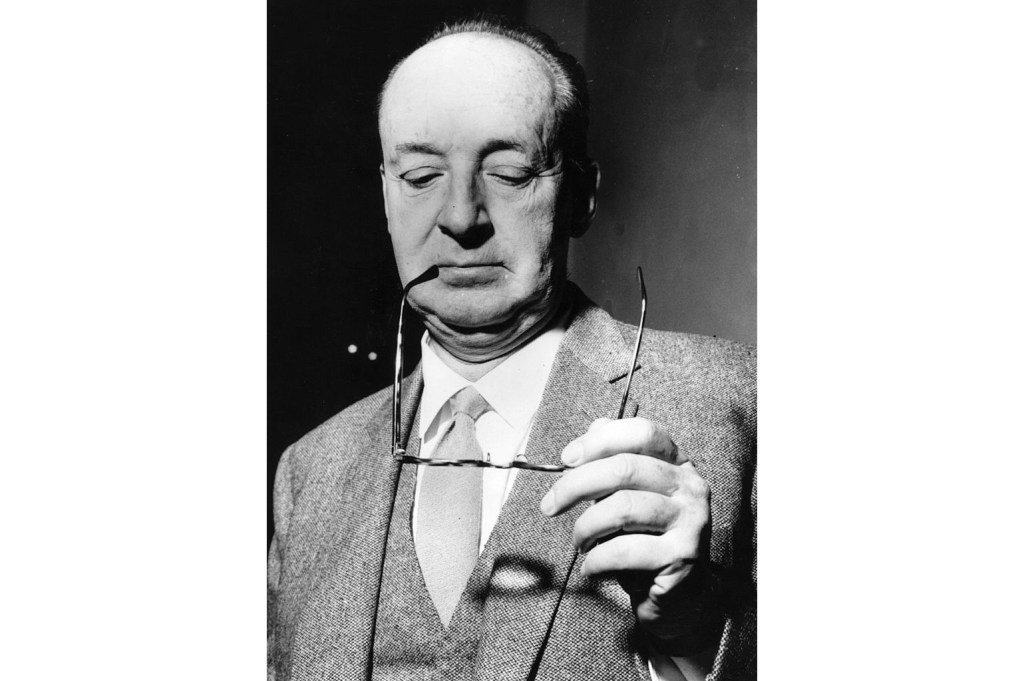

Not every novelist has opinions. Some of the very greatest have a touch of the idiot savant, like Adalbert Stifter, Ronald Firbank or Henry Green. And not every novelist with opinions is worth listening to. Vladimir Nabokov’s opinions, on the other hand, are of compelling interest because — paradoxically — he regularly and accurately insisted that his novels sent no message, made no moral case, presented no argument. The beauty and fascination of his views on literary and other matters rest, I think, on his openness to laughter.

Nabokov used to complain that his lectures to undergraduates at Wellesley and Cornell were greeted in silence; he was sure that if he had heard them, he would have been in fits of laughter from start to finish. The possibility of laughter, never very far away, is what gives Nabokov’s intelligence the confidence of the first-rate.

His non-fiction stands up astonishingly well. There is Speak, Memory, the greatest of autobiographies; Strong Opinions, an idiosyncratic collection of reviews and interviews, mostly from the early 1960s; and three masterly, intensely practical and hilarious volumes of lectures — on literature, on Russian literature and on Don Quixote. Think, Write, Speak is something of a mopping-up exercise, with uncollected and unpublished essays and reviews as well as a very large number of press interviews.

The interviews, I must say, could have been approached by the editors, Brian Boyd and Anastasia Tolstoy, in a more rational way. They have followed Nabokov’s eccentric practice in Strong Opinions of printing only his reported speech from each press interview, leaving out any scene-setting or commentary the journalist may have indulged in. There are four or five truly insightful ones — Penelope Gilliatt catches Nabokov in full flight for Vogue in 1966, and Robert H. Boyle gives a magnificent account of a butterfly-hunting expedition in a 1959 issue of the lepidopterist’s favorite, Sports Illustrated.

Not many journalists succeeded in making Nabokov talk about butterflies: he knew too much, and they knew nothing at all. Boyle somehow got him to speak generously about his second great passion, including the startling information that he once ate some butterflies in Vermont to see if they were poisonous: ‘The taste… was vile, but I had no ill effects. They tasted like almonds and perhaps a green cheese combination. I ate them raw.’

It would have been a very good idea to have included the whole of Boyle’s piece at the expense of several of the ridiculous interviews by Italian or German journalists: ‘Do you think that all creative and imaginative work is destined to disappear or to survive in America’s technological society?’ Apart from anything else, they all, without exception, ask the same questions about the morality of Lolita and what they regard as Nabokov’s inexplicable decision to live in Switzerland after 1961.

It’s true that even when talking to posturing dullards, Nabokov manages to sound interesting. Nonetheless, the main substance of the book lies in some remarkable essays, reviews and lectures. A hilarious de haut en bas lecture on ‘The Railway Accident’, a short story by Thomas Mann from the volume Nocturnes — ‘Nobody in their right mind would use the word Nocturnes for a title but let that pass’ — skewers Mann on every level: style, message-sending and practicality, noting that in Mann, one can put one’s fist through a window without having ‘a single scratch to show’.

There are other tirades on literary topics. A brilliant paragraph in the Gilliatt interview explains with joyous exuberance just how incompetent Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago is as a novel:

‘That marvelous scene where he had to get rid of the little girl to let the characters make love, and he sends her out skating. In Siberia. To keep warm they give her the mother’s scarf. And then she sleeps deeply in a hut while there is all this going on.’

What preserves this from being loweringly negative is Nabokov’s clear and happy sense of what fiction ought to be doing and how it can be made much better. He must have been a superb teacher. A 1943 profile shows him being utterly sweet to his pupils: ‘So good to hear Russian spoken again! I am practically back in Moscow!’ (Not, on reflection, an unmixed joy for Nabokov). The essay ‘On Learning Russian’ contains the joyous classroom observation that ‘A Russian vowel is an orange, an English vowel is a lemon’. For confirmation, observe the shape of your mouth when you pronounce the O’s in Tolstoy and in clothes.

Some of the bravest and most inspiring writing here comes in violently funny reviews of Soviet ‘literature’. Nabokov, who never tired of pointing out that the fortune he made from Lolita after 1955 didn’t begin to compensate him for the family money the Bolsheviks had confiscated after 1917, was at once selfish and principled in his loathing. ‘No literature,’ he rightly says, ‘can be expected to produce anything of permanent value when its only objective, as ruled by the State, is to embody this or that governmental whim.’

The fate of that essay, ‘Soviet Literature 1940’, proved his point. It was commissioned for a 1941 issue of Decision, an American periodical edited by Klaus Mann, and actually put into proof. It was pulled, however, under official pressure. Nabokov’s first lines compared a Nazi promulgation that though the artist ‘should develop freely’, the party ‘demand[s] acknowledgement of our creed’ with Lenin’s maxim, ‘Every artist has the right to create freely; but we, Communists, must guide him according to plan.’ After the German invasion of Russia, this observation was no longer welcome in the US.

Nabokov had a lot to laugh about. An earlier talk, ‘A Few Words on the Wretchedness of Soviet Fiction’, simply summarizes the action of Cement, a ludicrous novel by one Gladkov. The comedy is irresistible, but we are made aware of its chilling aspects: ‘Hello there, fellers! What a hell of a mess you’ve made of the factory, my friends! You ought all to be shot, my dear comrades!’

In the later essay, he dryly notes the terrified encomium of the Soviet novelist Marietta Shaginian on a state-approved Azerbaijani short story by ‘someone called Mamed-Kuli-Zade’, that ‘it is hardly possible to find in the literature of the whole world many stories that attain the same level of artistic force and social truth’.

Shaginian, having been condemned as ‘bourgeois’ and ‘decadent’ for early novels like Hydrocentral (1931), ended up writing interminable novels about the life of Lenin, which usefully won her the Lenin Prize. Nabokov, meanwhile, never won anything, which tells you everything you need to know about literary prizes.

Of course, it was all a performance. Any journalists who presumed to know what Nabokov really thought about anything, let alone those Italian idiots under the impression that Lolita had an autobiographical aspect, were quickly seen off. Did anyone know what was inside there? Did even Nabokov? Or was there just the splendor of his sentences, which can present feeling, impersonate it and retreat heartlessly from it, making the reader weep or laugh heartily when someone is horribly killed in two words: ‘(picnic, lightning)’?

Nobody knew, least of all the twit whose opinion that Nabokov had ‘never been too close to anybody’ called forth this splendid, gloriously conceited, but somehow tranquil observation: ‘One is often tempted to ask an opulent-looking stranger how much money he has in the bank; but he mumbles evasively.’

This article is in The Spectator’s November 2019 US edition. Subscribe here.