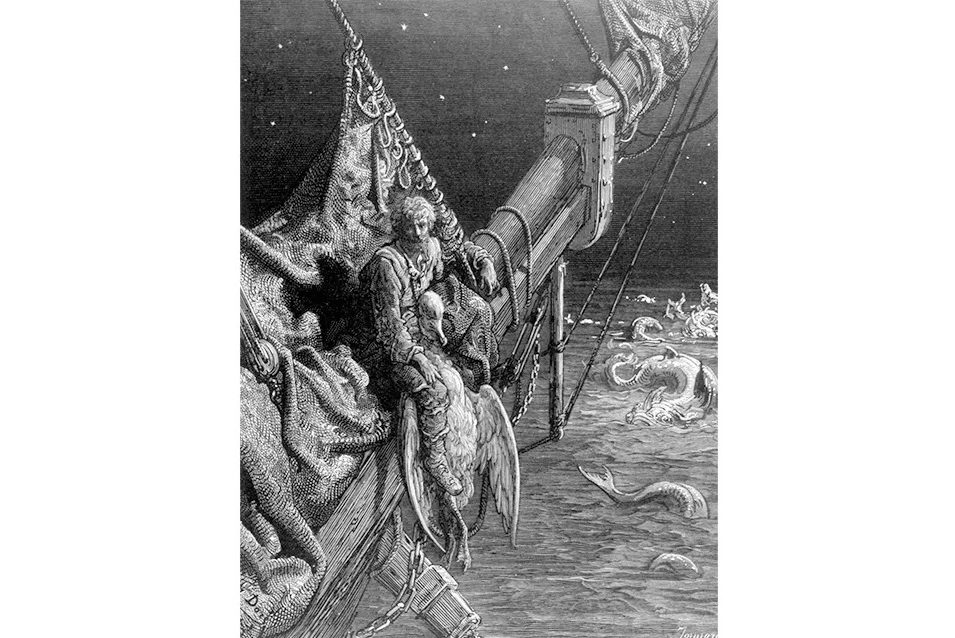

I’ve just returned from five days in the Lake District, attending the biennial “Friends of Coleridge” conference in Grasmere. All the other attendees were seasoned Coleridge scholars, but I was a newbie. The reason for my going was the fact that I’m engaged in a project that has at times felt something of a lonesome road and indeed an albatross: to write a book about Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” The poem comes to us with a vast undertow of explicit and implicit cultural and historical baggage, from its self-conscious antiquarian roots in late medieval ballads to its engagement with more currently pressing concerns of environmentalism and how we navigate the story of colonial expansion.

No other poem in the English canon has such viral reach today or is quoted with such abandon. “Water, water everywhere — let’s all have a drink!” says Homer Simpson in a 1993 episode. Taylor Swift’s most recent album, The Tortured Poets Department, released earlier this year, contains an homage in a song called “Albatross.”

When it was first published as the opening number in Lyrical Ballads — the joint volume by Wordsworth and Coleridge that kickstarted the English Romantic movement in 1798 — it was dismissed as “the strangest story of a cock and a bull that we ever saw on paper.” But within twenty years it was being confidently referred to in the literary press as a work with which “every reader of modern poetry is acquainted, of course,” and as a poem “which, when once read, can never afterwards be entirely forgotten.” Since then it has continued to work its uncanny magic over audiences that range from the youngest children to the most erudite academics.

The historian Lady Antonia Fraser, now in her nineties, once told me about how, as a child, she had squirreled away a book from her parents’ library and taken it to the nursery: it was The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. She read it, enthralled — but the odd thing about it, she recalls, was that whenever she got to the end she had to begin it again as she could never remember the story. That says something quite profound about the way in which the poem “plays tricks with the mind,” as the Romantic essayist Charles Lamb put it in 1798. It is a story about a man obsessed with retelling his story that has prompted obsession in culture at large because it never offers up closure.

“The Rime” remains an enigma. An awestruck J.G. Lockhart concluded in 1819: “To speak of it at all is extremely difficult… It is not capable of being described, analyzed, or criticized.” One of the conference attendees confessed to me that she always tried to get out of teaching it. That’s understandable. In 1981, the Romantics scholar Jerome McGann posed the problem in disarmingly bald terms: “What does ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ mean?”

To ask what it means is maybe the wrong question, since it’s a poem that questions the very foundations of meaning. If that sounds abstruse, you should have been at Grasmere, listening to the papers on metaphysics. This being a Coleridge conference, it was only too appropriate that the guide who took us out on an invigorating fell walk up Helm Crag — where a number of doughty intellectuals, a rope around their waists, ascended the rocky stone peak that sits on the summit like a knife — turned out to have a PhD in the mathematics of string theory. I was grateful that my walking boots weren’t half burnt, as Coleridge’s boots were by accident half way through his “wild journey” across Scotland in 1803 — the subject of the keynote lecture by Professor Nigel Leask of Glasgow University, in which he explored the poet’s innovations in writing about landscape.

In the popular imagination, Coleridge is remembered as the opium addict who wrote “Kubla Khan” under the influence. There were plenty of jokes among conference delegates about Kendal Black Drop — the local opiate when Coleridge was living in the Lakes — and why there wasn’t a tourist shop for it, like the famous Sarah Nelson’s Grasmere Gingerbread with its endless queues.

But Coleridge was so much more than that. Indeed, his was one of the most extraordinary minds ever recorded in detail, especially in his voluminous Notebooks that only surfaced last century. His most famous poetry was all written by the time he was thirty; but that constitutes only a tiny fraction of his labyrinthine lifetime output before he died in Highgate at sixty-one. No one of his era read more or thought more or wrote more. Probably the last individual in England who aspired to be a “universal genius,” he wanted above all to be remembered as a great philosopher, though his Opus Maximum remained unpublished at his death.

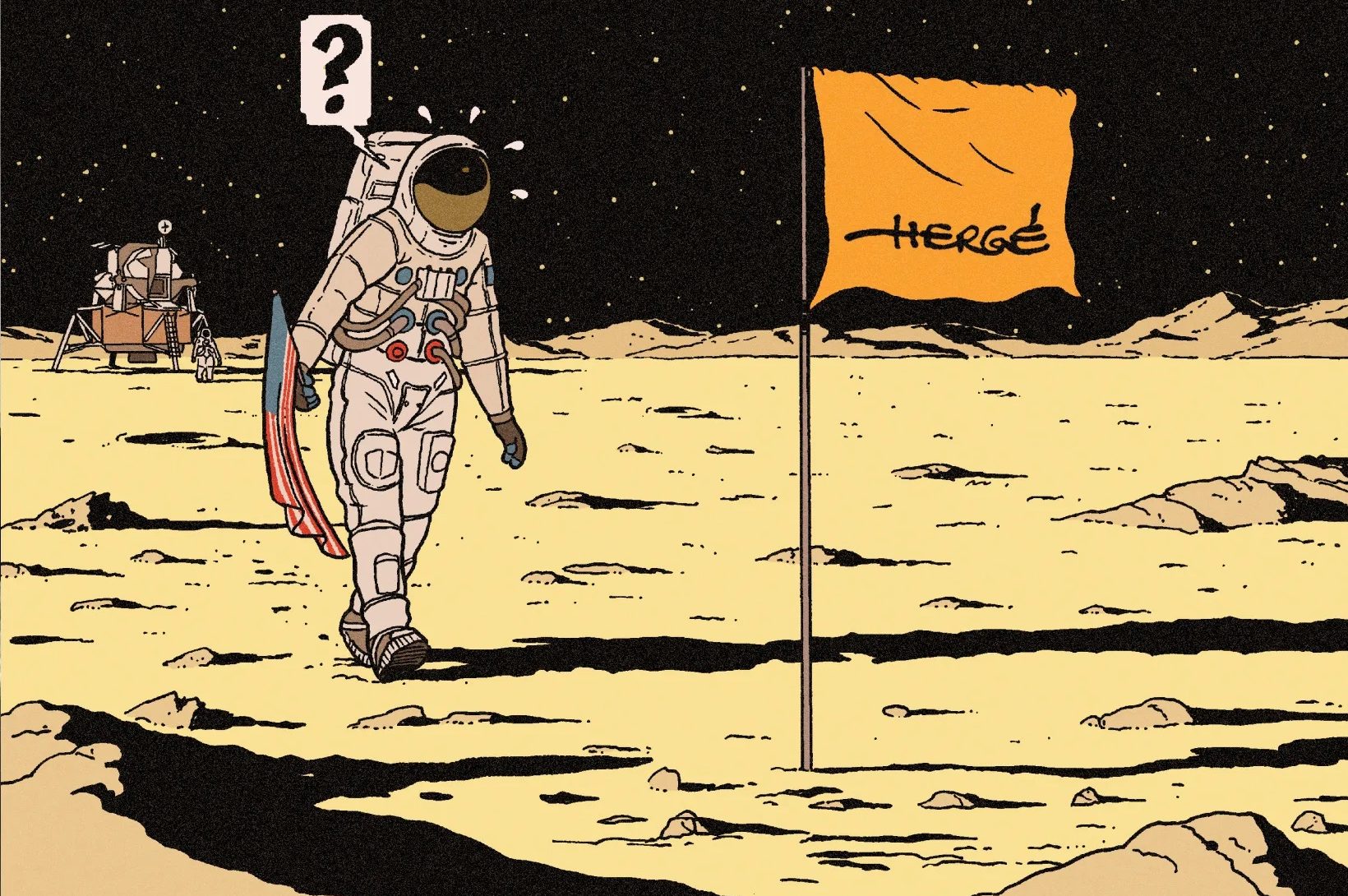

One of the speakers referred somewhat poignantly to the diminishing realm of literary history. Given the current emphasis on STEM in education, that’s not surprising. But the conference showed that literary studies, though under cultural and economic siege, are in fact in vigorous health and fighting back. One delegate had come from New Zealand, where he had watched real albatrosses in Auckland in breaks from scholarship. Another had literally come from Xanadu — a young academic from Mongolia, who presented a paper on the influence of Daoism on Coleridge. Sounds far-fetched? Not at all. She had evidence to suggest he’d read up on the subject.

Coleridge notoriously had terrible trouble maintaining relationships — witness his broken marriage and his difficult friendship with Wordsworth. By contrast, there was a warm atmosphere of untrammeled mutual intellectual sharing at the conference under the benign horn-rim-bespectacled stewardship of Professor Tim Fulford, the editor of the recent Cambridge Companion to Coleridge.

They were at least kind enough to laugh at my jokes when, as an outsider, I gave the final talk at the conference, though I remain painfully alert to the advice Coleridge offered in capital letters in the eleventh chapter of his Biographia Literaria: “NEVER PURSUE LITERATURE AS A TRADE.” I only hope that the paper I gave won’t prove as chimerical a promise, when it comes to actually finishing my book, as did Coleridge’s reference, at the end of the thirteenth chapter of the Biographia, to “the critical essay on the uses of the supernatural in poetry and the principles that regulate its introduction: which the reader will find prefixed to the poem of The Ancient Mariner.” No such essay was ever published, and no draft of it has ever been found.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.