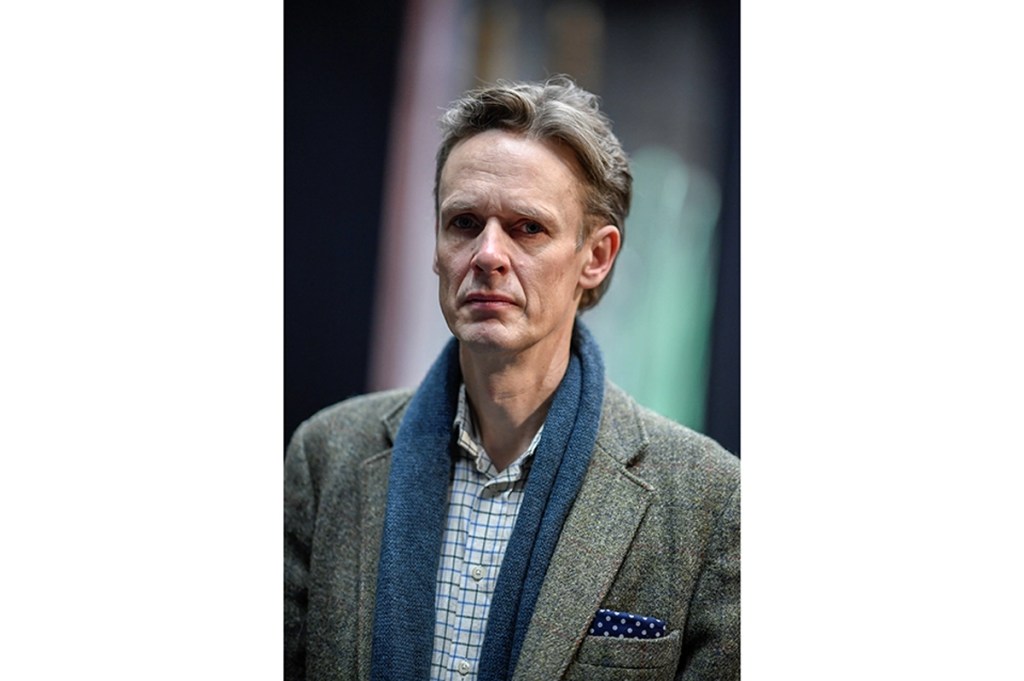

The professional performer is the tree in the philosopher’s human forest. If there’s no opportunity to sing or act or dance in front of an audience, are they still a performer at all? In the spring of 2020, when most of his colleagues shrugged and started making banana bread, the tenor Ian Bostridge took an altogether more existential approach to isolation, writing a series of lectures for the University of Chicago exploring the relationship between self and singer, silence and song. Now they form the basis of his latest book.

Song & Self is a slim volume. Early on, Bostridge invokes the essay’s origins in Montaigne — the idea of essayer (to try), the form as a space for experimentation and exploration, for provisional attempts rather than finished thoughts or arguments. It’s framed as an apologia; Bostridge’s writing is an “open-ended performance,” “improvisatory rather than systemically theorized.” The book comes to life when it does precisely that: shakes free of thesis and academic jargon and stops scaffolding itself with critical theory.

Bostridge has the ability to perch on his own shoulder as a performer and expose the process to us onlookers

Before he was a professional singer, Bostridge was a historian and Oxford research fellow. If you fancy an unexpected diversion from listening to his impressive and much-awarded recording catalog, you could read his monograph Witchcraft and its Transformations c.1650-c.1750. It’s as though, in lockdown, Bostridge reverted to this earlier self. While his previous A Singer’s Notebook and Schubert’s Winter Journey smuggle profundity in under the jumper and jeans of relaxed, readable prose, Song & Self wears its scholarship as a suit of armor — and not one that’s been oiled recently.

There’s quite a lot of problematizing, historicizing and “othering,” a healthy dollop of Fanon and Gramsci, and not much by way of translations (so best brush up your French and German before you start). Bostridge’s aim is to “examine performative constructions of identity in music through the lens of gender, politics or the ultimate paradoxical grounding and denial of identity: death.” But it’s definitely not a thesis, OK?

The thing is, when Bostridge forgets he’s an academic and just writes, it’s magic. His ability not only to sing this vast repertoire (the book roams from Monteverdi to Benjamin Britten, by way of Schumann and Ravel) but also to stand back from it and unpick the hows and whys of performance — translating his instinctive reactions and resistances into fully fleshed-out arguments, all rooted in a gloriously broad frame of cultural reference — is singular. His potted histories of French colonialism and the traditions of Japanese theater are interesting, but his ability to perch on his own shoulder as a performer and expose the process, the profession itself, to us onlookers is much more so.

How, he asks, does the role of the singer change from opera to song? If opera is acting, concealing self behind a character, then where does that leave the singer (not to mention the pianist) in the concert hall, caught somewhere between ventriloquist and dummy? And then there’s the question of interpretation, which we tend to take for granted in classical music, because the alternative could set the whole lot toppling down on us. Bostridge risks poking at the foundations of what he describes as the “part shamanic, part scientific quest for the ‘right’ performance,” and the dust cloud he sends up suggests he’s found the right spot.

He admits the tensions within his project in his final and most ambitious essay, “Meditations on Death.” “As so often in the song repertoire,” he writes, “formal analysis… tells us one thing, performance another.” It’s performance’s perspective that’s often absent elsewhere, and this that Bostridge does so well. There’s a bracing plunge into the conflicts of Britten’s “The Holy Sonnets of John Donne” that mines “Thou hast made me, And shall thy worke decay?” for fragments of concealed meaning, playing text and music off against each other thrillingly, as well as a passing glance at the postlude of Schumann’s cycle Frauenliebe und Leben that will send you straight back to listen (and think) again.

Monteverdi’s opera-in-miniature Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda gives up some of its strange and sensual secrets (even if things do get a bit heavy-handed when it comes to “challenging the trope of heteronormativity”), while Bostridge’s own experience of performing Ravel’s Chansons madécasses, with their complicated layers of colonial history and racial perspective, throws uneasy personal light on a cycle no program note can ever fully hope — or perhaps want — to contextualize. Best of all is the writing on Britten – a composer whose musical language Bostridge has such an affinity for, both on and off stage.

Song & Self is at its best when it tinkers around inside the engine, lends the reader some critical tools and invites one to have a go too. Who wouldn’t rather join a master-craftsman in his workshop, shadow him at his art and eavesdrop on his inner monologue than hear it analyzed at arm’s length in the lecture hall?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.