On February 1, 2024, Sotheby’s auction house announced a new fee structure that came as something of a surprise to the art world. For decades, Sotheby’s and its competitors have been one-upping each other with respect to the fees charged to buyers and sellers. While these fees have unquestionably increased the profitability of the auction houses themselves, in their complexity they have often bewildered auction participants and market observers alike. In theory at least, that may be about to change.

Beginning this spring, Sotheby’s new fees will be both lower and potentially easier for all parties to understand. They apply to sellers consigning lots for auction after April 15, and to buyers beginning on May 20. While the fee calculations will be standardized across Sotheby’s global salerooms and apply to sales of fine and decorative art, the new rates will not apply to certain types of auctions, such as of cars, real estate or wine and spirits. Overall, whether the auction is held in New York, London or Zurich, both buyers and sellers should see their fees drop, relative to those they would have incurred previously.

There is much to unpack in Sotheby’s thinking about its latest move. The stated desire to pivot away from private sales, for example, is interesting since such transactions have been an important part of its revenue stream. Yet perhaps most interesting of all in the immediate term is the potential impact on the art market of Sotheby’s decision to reduce and simplify its “buyer’s premium.”

As Mari-Claudia Jiménez, Sotheby’s chairman and president for the Americas and head of global business development, explains, the buyer’s premium “is essentially a commission equal to a portion of the overall price that buyers at auction pay when they place a winning bid.” Auction houses usually calculate this fee as a percentage of the “hammer price,” as the winning bid is often referred to. “For instance, under the revised buyer’s premium structure that we will implement in May this year,” Jiménez notes, “if a lot sells for $500,000, the buyer’s all-in purchase price before any applicable taxes due is $600,000 — which is the hammer price plus the 20 percent buyer’s premium.”

“The buyer’s premium portion of the sale price is recouped by Sotheby’s, or any auction house, as a service fee for our ability to successfully bring together a buyer and a seller,” explains Jiménez, “and generally covers the research, expertise, global marketing and other costs associated with conducting auctions.”

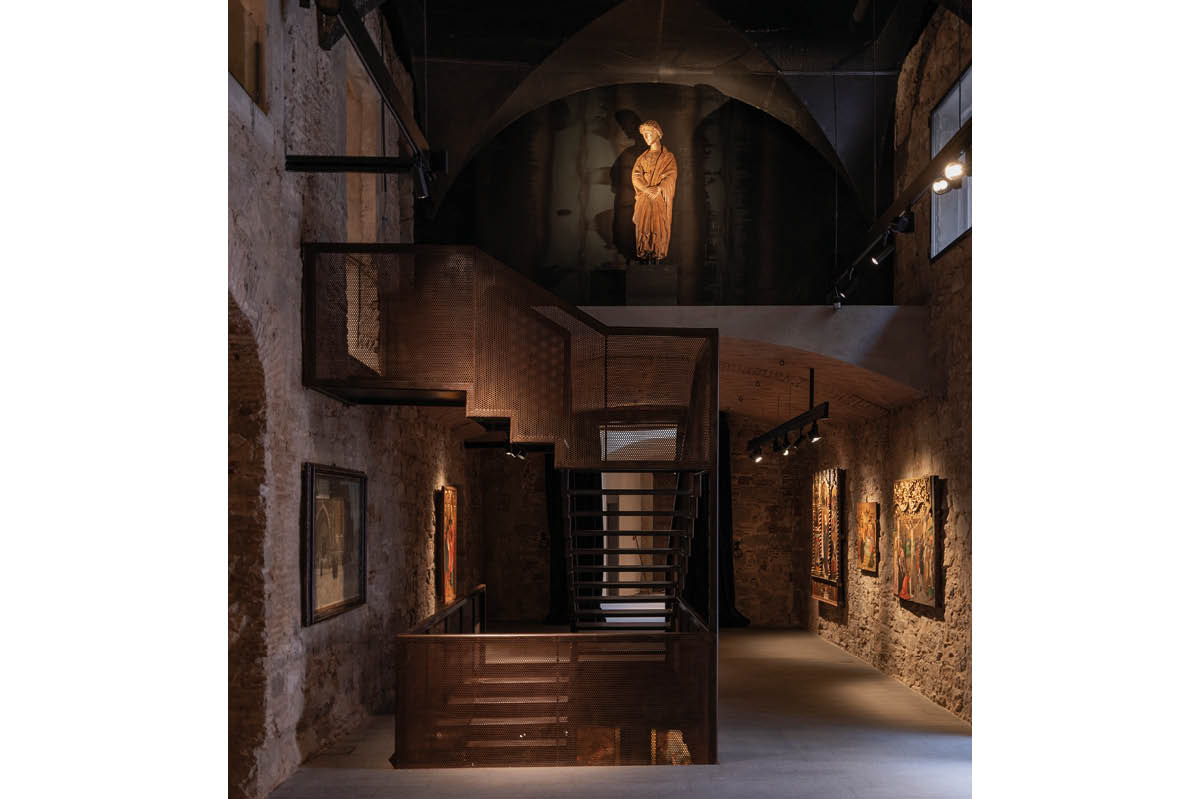

In an increasingly sophisticated and international art market, such services are relied upon by both buyers and sellers. Sending an important painting on an international tour to attract potential bidders, identifying where an ancient sculpture came from or obtaining an expert opinion as to whether a drawing is by a particular artist are typical auction-house activities that all carry significant costs.

Sotheby’s decision to reduce and simplify the calculation of its buyer’s premium involves a major change to its existing system of tiered fee assessment, as Jiménez observes. “Our current rates, which will be replaced by the new model in May, are broken down into three percentage tiers that apply globally, with the only difference across selling locations being the conversion rate for the value bands. With the new model, we are simplifying the structure to eliminate an entire tier and make the percentages easier to calculate. Under the new model, buyers will pay 20 percent of the hammer price up to $6 million, and 10 percent on the portion of the hammer price exceeding $6 million.”

Sotheby’s goal, says Jiménez, was to maintain an overall equilibrium throughout the international locations where it conducts business. “In standardizing the buyer’s premium structure for sales globally,” she says, “we create a level playing field for bidders around the world. Our sales are more global than they ever have been, with bidders participating in sales in their own regions and beyond, so it is important for us that our rate be consistent and not favor one region over another.”

You might question whether the change could have an impact on where buyers choose to engage with the auction market, even if the fees are globally applied, should buyers choose one market over another to chase more favorable currency rates. However, Jiménez does not believe that this will be the case. “The buyer’s premium rate is consistent around the world,” she observes, “adjusted for local currency exchange rates, so I do not think the rate will have any effect on the region where sellers and buyers opt to transact. Collectors are driven by passion and will participate in a sale where there is a work they are interested in acquiring, regardless of location.”

Understanding the passion that underlies art collecting was part of why Sotheby’s adopted the buyer’s premium in the first place. Collectors who really want to acquire a particular work, the thinking goes, will be willing to pay a commission to an auction house above and beyond the hammer price to obtain it. However, in order to truly understand the significance of the buyer’s premium and its impact on the art market, you need to understand the past history and current positioning of Sotheby’s and Christie’s, the two biggest players in the auction world.

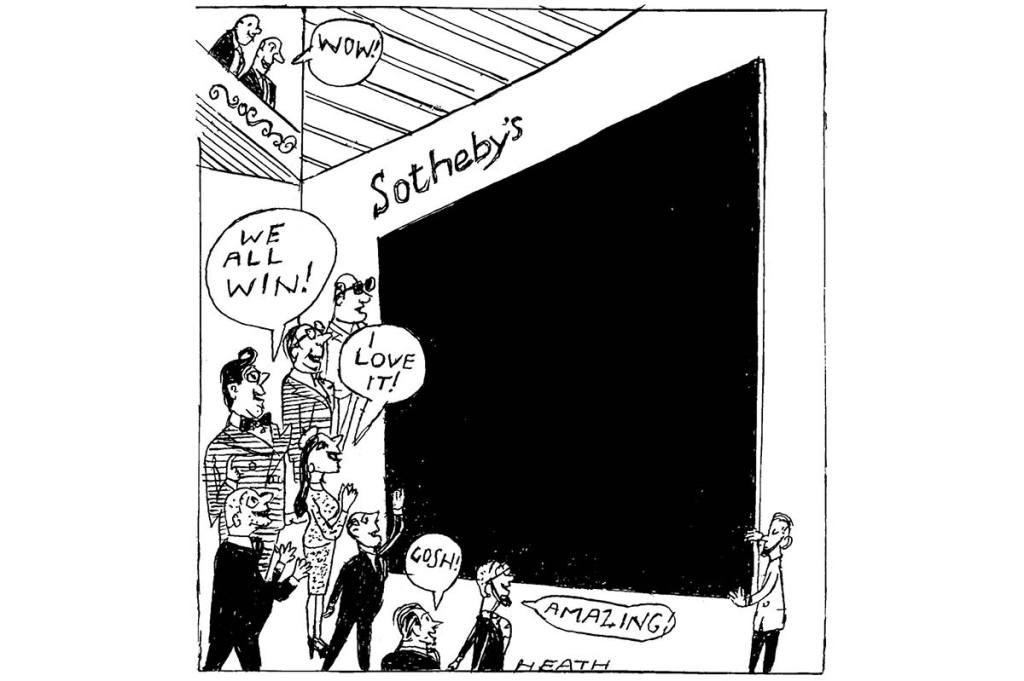

Not long after Sotheby’s and Christie’s became publicly traded corporations back in the 1970s, following centuries of being privately held, both companies began charging buyer’s premiums to increase profitability for their shareholders. Although the buyer’s premium already existed in other types of auctions such as real estate, it had never been applied in art auctions. Naturally enough, at first the buyer’s premium was highly criticized.

Some art-market experts predicted that the buyer’s premium would put off potential bidders, such as smaller nonprofit institutions or individual collectors without large sums at their disposal. Art dealers, meanwhile, complained that the buyer’s premium would dramatically eat into their profits, since dealers often purchase a work at auction and then turn round and sell it for a higher price, pocketing the difference. Despite such criticisms, with the implementation of the buyer’s premium, profits at both Sotheby’s and Christie’s began to grow exponentially, and other auction houses followed their lead by charging their own buyer’s premiums.

Eventually the buyer’s premium became common across the art auction industry, and today you would be hard-pressed to find an auction house that does not impose one. What’s more, over the years whenever Sotheby’s would raise its buyer’s premium or add additional fees, Christie’s quickly moved to do the same, and vice versa. This, in turn, would cause a domino effect among the midsized and smaller auction houses, which raised their own buyer’s premiums in response. As time went on, auction houses adopted increasingly complicated formulae for calculating buyer’s premiums, again often following the lead of the industry’s two largest competitors.

Jiménez admits that since it was introduced in the 1970s, the buyer’s premium has shifted costs that used to be borne by the seller, or by the auction house itself, almost exclusively onto the buyer. Hence the seemingly neverending upward trend in buyer’s premiums, as auction houses have sought new ways to cover their costs while increasing profits. Sotheby’s is clearly hoping that its decision to reduce and simplify its buyer’s premium will ultimately benefit all parties, by subtly encouraging bidders to bid higher than they might have previously, thanks to the reduced premium, thereby potentially increasing returns for the seller — and by extension for the auction house itself.

“With the overall reduction in our buyer’s premium — an average reduction of about 26 percent — and simplified rates, we anticipate more bidding activity at auction,” Jiménez says, “which will deliver higher hammer prices for sellers. What’s good for the buyer is good for the seller.”

While existing buyers will no doubt appreciate being charged lower commissions when they do business with Sotheby’s, the primary motivation behind the reduction and simplification of the buyer’s premium appears calculated to attract more potential buyers. For beyond whatever practical impact Sotheby’s decision may have in reducing barriers to entry among existing buyers, the change more importantly reduces perceived barriers to entry among those who have never participated in an art auction before. With a clearer, simplified buyer’s premium, more potential buyers may be willing not only to enter the art auction marketplace, but to spend more once they get there.

Sotheby’s is clearly betting that it can increase its profits through achieving higher sales figures resulting from lowered commission rates, rather than through the imposition of another round of fee hikes. This is quite a sea change from the periodic tit-for-tat commission increases that have characterized the art auction market for decades. And the strategy may well have to do with the fact that the playing field between Sotheby’s and Christie’s has altered significantly in recent years.

As of today, the world’s two largest auction houses are no longer listed on the New York Stock Exchange: Christie’s went private in 1998 and Sotheby’s in 2019. Both voluntarily make certain aspects of their balance sheets available, but as privately held corporations are not required to disclose their books to the same extent as are publicly traded firms. Thus far, Christie’s has not announced whether it will make any changes to its fee structure based on Sotheby’s move, but it’s not unreasonable to assume that it will be forced to do so to stay competitive.

It isn’t clear how the smaller auction houses, which have often tried to keep pace with the industry giants, will choose to respond. Can they afford to make a significant reduction in their fees? Will there be contraction and consolidation, or will some of them exit the market entirely? Will a new swath of bidders, attracted to art auctions for the first time, eventually find their way to these other auctioneers, if competition at the highest levels proves too difficult to enter, even with the reduction in buyer’s premiums? Will dealers find themselves further priced out of the auction marketplace by this projected increase in new bidders with greater purchasing power? It’s simply too early to tell what Sotheby’s move will mean for the art market as a whole.

That said, it’s important to keep in mind that no matter how much we may love it, art is ultimately a luxury good, not a necessity. While a potential seller may feel compelled to consign a work of art for auction given certain circumstances — such as when faced with the three “D’s” (death, debt, divorce) — a potential buyer does not need to purchase a work of art. The challenge for any art auctioneer is to persuade potential buyers that, all things being equal, they would enjoy owning a work of art more than they would enjoy owning something else. Time will tell whether Sotheby’s latest gamble will persuade more potential buyers to agree with this assessment.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply