It is not hyperbole to call Stephen King the most influential horror writer alive. Across page and screen alike, nobody else can claim to have had such an expansive and lasting impact on popular culture. King’s name has become so commonplace that it’s easy to take it and him for granted, and to forget that behind the ultrafamiliar and now-ubiquitous branding there lies, in fact, a wild and strikingly original mind and a beating, bloody, passionate heart.

You Like It Darker, King’s latest offering, is a highly accomplished and masterful collection of twelve short (and not so short) stories, all blistering examples of King’s powers. Though some have seen the light of day elsewhere, most are published here for the first time. All are worth the purchase.

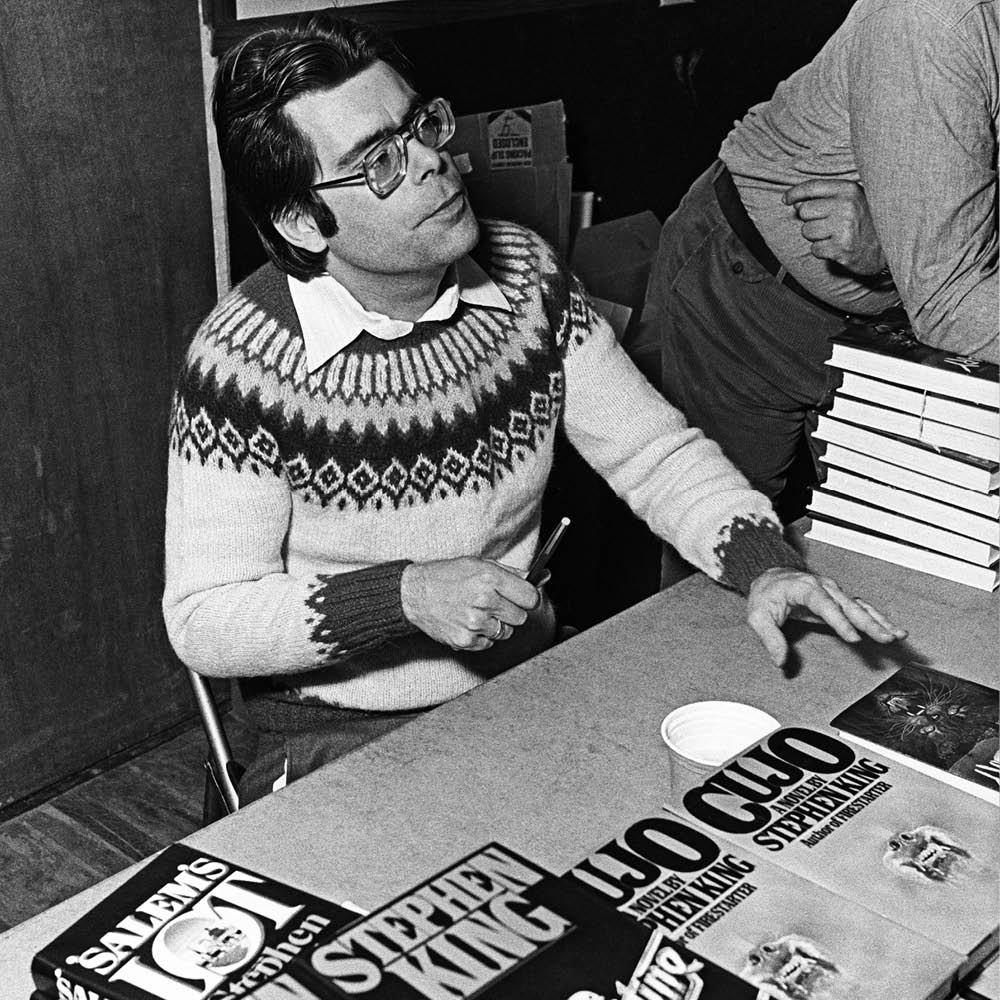

The book inevitably harks back to Carrie, King’s debut novel, published fifty years ago this spring. Carrie was an immediate hit, and its place in the canon was permanently secured by the seminal film adaptation that followed two years later. The notion of a “cultural canon” is important when discussing King: his work is astonishingly adaptable, and his cinematic offspring have consistently joined the ranks of the Objectively Great (The Shawshank Redemption, The Green Mile, Misery, Stand By Me, The Shining: the list goes on). The original film of Carrie is arrestingly good — and for a nearly half-century old movie, so redolent of its time, the immediacy it retains is invigorating.

Earlier this year the novel was re-released in a special anniversary edition, with a new introduction by Margaret Atwood, highlighting the book’s feminist values. The two volumes work well read together, though I hope they do not turn out to be the bookends of his career — his new book is titled after Leonard Cohen’s final studio album, You Want It Darker, released just sixteen days before Cohen’s death and widely considered to be a self-conscious conclusion to, and commentary on, his life’s work.

The inherently fragmentary nature of short story collections means that Darker chimes subtly with the epistolary style of Carrie, in which the narrative is pieced together using newspaper reports, witness interviews, and so forth (much as Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker did with Frankenstein and Dracula). The sum of its twelve tales ultimately pieces together something deeper than their individual plots. The exploration of and anxiety around writing and talent that defines the first, “Two Talented Bastids,” has obvious resonance; the addict cataloging his life’s strengths and failings in “Fifth Step” and the exploration of old age and mortality in “Willie the Weirdo,” “On Slide Inn Road,” “Laurie” and “Rattlesnakes” (a sequel to Cujo) do likewise.

Though I may be reading too much into it, I can’t help but see the hint of a breadcrumb trail in “Willie the Weirdo,” when King references the famously semi-autobiographical novel A Day No Pigs Would Die, written by and featuring Robert Peck. “Two Talented Bastids” discusses metafiction at some length — and the fictional author appears in his own work, where a favorite review of his debut novel is also quoted: “Not much happens in the first hundred or so pages of Mr. Carmody’s suspenseful yarn, but the reader is drawn on anyway, because there are violins.” This brilliant story opens the collection, and it is King at his best — utterly invigorating, finding the magic in the humdrum. There are most definitely violins.

King often writes about writers, and it is impossible not to see him in this collection. He is famously close to his family — he has collaborated professionally with both his sons and been married for fifty-three years — so it is no surprise to find story after story dwelling on the horrors of the elderly widower, lost and empty, or the intensifying pitch of loneliness in the old and childless.

Old age features constantly in these stories. Sometimes the old are evil, sometimes mad, often heroic — but for King they are always powerful. Always rich and complex and possessed of half-glimpsed secrets that the generation below them are too self-absorbed and pompous to notice, but which the generation below them feel inexplicably drawn toward. King leans heavily into the grotesque, inevitable indignities of age and infirmity, of its cruelty, but through it he finds something near to grace, to nobility.

Covid shows up in many of the stories — sometimes just as a passing reference, sometimes as a plot point. (When the pandemic began, many pointed out apparent similarities between its spread and the plot of King’s 1978 novel The Stand, although the author played it down.) King is admirable in his ability to write in an ever-developing present, and not merely to keep his peak years in aspic; his characters do not exist in a world without cell phones, social media or tablets. Though these nods occasionally stand out a little awkwardly (“we have Spotify” roar some torturers in “Finn”), for a man whose work covers seventy titles over half a century this demonstrates an impressive commitment to retaining a connection to the confusing world-as-is, not just the profitable world-as-was.

King has always been vocal about his politics, and at first glance the stories have a tendency to echo his positions — the aged writer in “Bastids” “didn’t vote for Trump the second time. Couldn’t bring himself to vote for Biden, but he had a bellyful of the Donald.” The regular appearance of this take, alongside some superfluous interposed modernisms (“you can google it”), can sometimes feel forced and unnecessary.

However, after an internal monologue in “Road,” in which a middle-aged son castigates his elderly father for the racism, homophobia and misogyny inherent in his generation, it is the problematic, repugnant old man who must risk himself to save his family, and the pompous, progressive son who fails when it really counts. King is not simplistic.

In 2021 he caused a stir by speaking publicly about being blocked on Twitter by J.K. Rowling for having disagreed with her position on trans issues (his third child, a Unitarian minister, currently identifies as gender-queer). The internet exploded at this, supporting him and attacking Rowling, prompting King to tweet: “My opinion is that Jo Rowling is wrong about trans women. Leave shitty and hateful out of it, please.” He later went into more detail, saying “she is welcome to her opinion. That’s the way that the world works. If she thinks that trans women are dangerous or that trans women are somehow not women… she has a right to her opinion.”

Though a decade or two ago this would have seemed an obvious position, today it is a brave one, and a bold statement. His embrace of the role of centrist-boomer-dad provoked outrage among some younger followers, and last year King was denounced for praising Rowling’s recent crime thriller, The Running Grave. “J.K. Rowling at her best,” he said, “recalling the sheer readability of the Harry Potter books, but much darker. This got me through a difficult time.” Despite the flak he received for daring to prioritize art over activism, King includes a respectful mention of her in You Like It Darker, with a wry and humble nod to the fact that her astonishing wealth and relatively recent success dwarf his own; there are very few writers for whom that is the case.

The key to unlocking this morality, which reads as hypocrisy to the childish, is that King worships story. He is a loyal lover of writers and of readers, and this is more important to him than anything so shallow as politics. In his afterword he writes that “horror stories are best appreciated by those who are compassionate and empathetic. A paradox, but a true one. I believe it is the unimaginative among us, those incapable of appreciating the dark side of make-believe, who have been responsible for most of the world’s woes.” I believe he is right.

If You Like It Darker is the goodbye that its title implies (and I cannot bring myself to believe it is, for a writer as prodigious as King can surely not just stop), then it is a worthy goodbye. Those who dislike King’s work will find plenty to dislike, but those who love it will find far more to love. The final page concludes: “Great thanks to you, dear readers, for allowing me to inhabit your imaginations and your nerve-endings. You like it darker? Fine. So do I, and that makes me your soul brother.”

Few could write this and really, truly mean it. King does. It is that heartfelt, Maine-bred authenticity that has always been at the core of his art and his success. Perhaps the best summing-up is, again, from the mouth of the aged author in “Two Talented Bastids.” “Butch was a fine artist, but he was also a good man. I think that’s more important.” Stephen King is both.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply