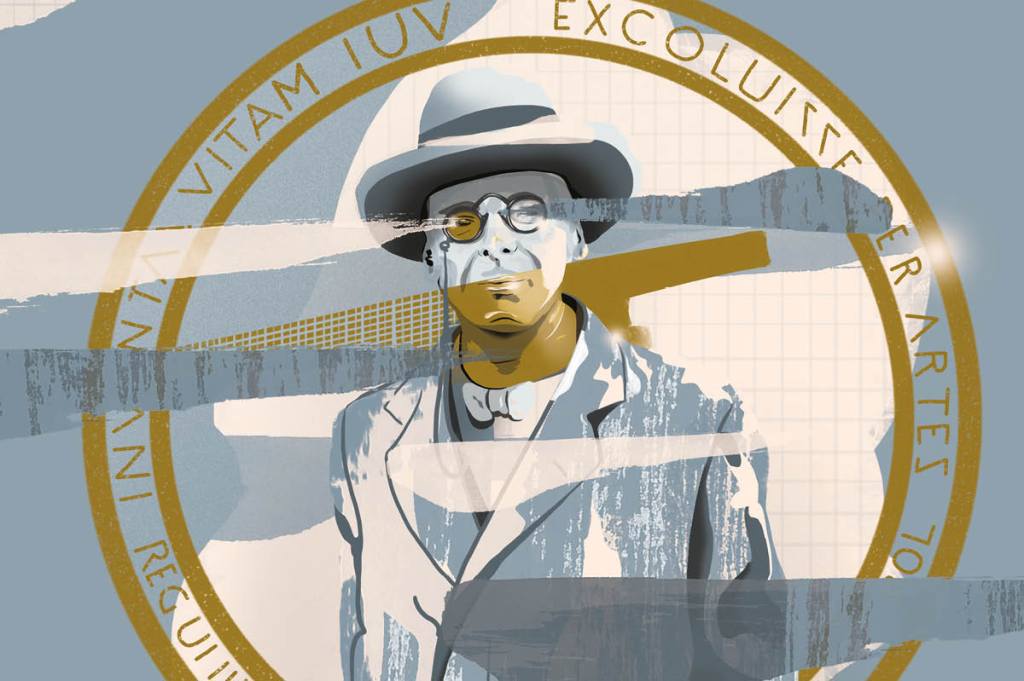

The 1923 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to William Butler Yeats “for his always inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation.” Informed of the prize late on the night of November 14 by the editor of the Irish Times, the fifty-eight-year-old Yeats and his wife George sat up taking telephone calls and telegrams for a couple of hours. Then, according to Yeats’s sister Lily, the couple went down to the kitchen and cooked some sausages before going to bed.

The next day, the Yeatses went out and began spending some of the check Yeats would receive in December. He wrote his close friend Augusta, Lady Gregory, that they purchased “book cases, stair carpets, a carpet for the study, plates dishes, knives & forks & something I have always longed for a sufficient reference library… As I look at the long rows of substantial backs I am conscious of growing learned minute by minute.”

Told earlier in the year that his name was under consideration by the Swedish Academy, which awards the prize, Yeats had said he was certain that Thomas Mann (who won the Nobel in 1929) would be named Laureate in Literature. However, in the immediate aftermath of World War One, the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, and the establishment in December 1922 of the Irish Free State, his prize quickly made political sense to the newly minted Senator Yeats. As his biographer Roy Foster put it, “An Irish winner of the prize, a year after Ireland gained its independence, had a symbolic value in the world’s eyes, and [Yeats] was careful to point this out. His reply to the many letters of congratulation was consistent: ‘I consider that this honour has come to me less as an individual than as a representative of Irish literature, it is part of Europe’s welcome to the Free State.’”

Yeats was awarded the Nobel because he was a voice of independence for a small, long-oppressed nation. By 1923, though, Yeats was no longer the last Romantic nor a nationalistically political poet — the would-be nationalist versus the artist had long been a vexed tension for him — nor was he any longer concerned with creating and promulgating an Irish mythology and literature, as he’d been during the days of the Celtic Twilight. He was immersed in the research that became A Vision (1925) and in writing his own memoirs, those mutable, demi-autobiographical accounts that contradict themselves from volume to volume and sometimes page to page.

Yeats was well on the way to becoming the Great Late Yeats, hieratic and constantly self-reflective, high and solitary and stern but just self-deprecating enough to retain some powerful humanity in his increasingly spare High Modern poems. However, he made the choice to look back at a narrow slice of his long career, and perform a particular past version of himself, as he accepted the prize. Yeats’s book about the trip, which includes his Nobel lecture, is the grandly titled The Bounty of Sweden: A Meditation, and a Lecture Delivered Before the Royal Swedish Academy and Certain Notes, first published in 1925 in a limited edition by his sisters Lily and Lolly at their Cuala Press. His actual lecture doesn’t begin until the thirty-third page; personal memories of the lead-up to the award and his time in Stockholm come first. Yeats also emphatically discounts both his early lyric poetry and his own process of composition, claiming that when his imagination is stirred he begins “talking to myself,” speaking dramatically “much as I have seen a mad old woman do on the Dublin quays,” and only occasionally writing out “what I have said in verse, and generally, for no better reason, than because I remember I have written no verse for a long time.”

Yeats’s Nobel lecture, “The Irish Dramatic Movement,” continues the denial of his poetry, insisting that he’s received the prize for his theater work. “If I had been a lyric poet only, if I had not become through this theatre, the representative of a public movement, I doubt if the English Committees would have placed my name upon that list, from which the Swedish Academy selects its prize winner.”

At the best of times, it is difficult to argue with Yeats; when he’s been named Laureate in Literature and is telling the world why that is, protesting seems futile — even if he’s revising his own career and opinions as he speaks. His pronouncements drop like stones. The modern literature of Ireland began in 1891 with the fall of Parnell. When he met Lady Gregory in 1896, only then did a national theater, formerly just a romantic notion he’d had, become possible. He commends both her plays and those of John Millington Synge, which were more popular at the time, and have continued to be, than Yeats’s own. However, Yeats also insists on his own role in making both these friends recognize and begin to use their own literary creativity.

Concluding his lecture with the wish that Synge, then long dead, and Gregory stood beside him, Yeats turned, oddly and paradoxically, for his final thought to admire the spectacle of the Swedish court and the “intellect of its country,” and speak of Ireland’s comparative impoverishment. A dramatic movement is both symbolic and commendable in execution, but Yeats suddenly wonders if it can fill “a need of the race no institution created by English or American democracy can satisfy.” That use of the word “race” rather than, say, “nation” to apply to the Irish is jarring, a disquieting reminder of the pseudo-neoclassical fascism of Mussolini that briefly intrigued Yeats and other intellectuals and artists — most regrettably, and over the long term, Ezra Pound — in the early 1920s.

The Yeats who accepted the Nobel prize was a very performative version of himself, a not-quite sixty-year-old smiling public man emphasizing certain things about “William Butler Yeats,” and eliding many more. He placed his own artistic accomplishments and those of his friends in the Irish Literary Revival, especially those who with him founded the Irish Literary Theatre, at the heart of recent past history in a remarkably powerful way for something so potentially self-aggrandizing.

In a foretaste of that famous, or infamous, line in “The Man and The Echo” (1938) “Did that play of mine [Cathleen ni Houlihan] send out / Certain men the English shot?” Yeats said in his lecture, “Indeed the young Ministers and party politicians of the Free State have had I think some of their education from our plays… we have come through war and civil war and audiences grow thin when there is firing in the streets. We have however survived so much that I believe in our luck, and think that I have a right to say my lecture ends in the middle or even perhaps at the beginning of the story.”

Those poems of wartime included in Michael Robartes and the Dancer (1921) were likely the leading reason Yeats received the prize, but by 1923 he was already far past those poems, many composed in the previous decade. And so is Ireland not the land of an Easter Rising by then, nor of civil war, but a forming state seeking self-identification beyond stereotype and the centuries-long imposition of another culture.

Robartes includes the poems “Easter, 1916” — written in the fall of its title year, but unpublished until 1920 — and its lesser-known (and lesser) companions “Sixteen Dead Men” and “The Rose Tree”; “On A Political Prisoner” (for the Irish politicians Constance Markievicz and Maud Gonne, who were both prisoners at Holloway in 1918); “The Second Coming”; and “A Meditation In Time of War.” By 1922, Yeats was writing the personal mythmaking poems of The Tower, and by 1923 he was experimenting with short, powerful detonations, in the Modern style he’d been honing and perfecting, a million miles from the Nineties. “Leda And the Swan,” the poem he’d been working on when he received news of the Nobel, might be a sonnet, but compare it to “When You Are Old” (1891) and the difference is astounding.

In 1932, reading his poems for a BBC radio broadcast, Yeats began with “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” (1888), which he’d written when he was twenty-three. He prefaced his reading with “if you know anything about me, you will expect me to begin with it. It is the only poem of mine which is very widely known.” Most of his ten BBC broadcasts in the 1930s included this poem. The Nobel was firmly in his past, and his days of public performance were no longer political or dramatic but far more relaxed with the accumulation of yet more laurels. His new poems surging with a power of which he was immensely proud, Yeats no longer deprecated the earlier work of his pen.

Far from it: even on his deathbed in Roquebrune in January 1939, while Yeats was revising “Under Ben Bulben,” the poem containing his epitaph, he asked that a lyric poem be the last one printed in his final vol- ume of poems. It is called “Politics” and isn’t about politics at all. It feels rather like a positive version of Yeats’s musing on his prize medal’s engraving. Taking his epigraph — “In our time the destiny of man presents its meanings in political terms” — from fellow laureate Thomas Mann, and then flipping it on its head, Yeats embraces the rhyme and rhythm and lyric beauty for which he not only had won his Nobel, but for which he was, and is, loved.

How can I, that girl standing there, My attention fix On Roman or on Russian Or on Spanish politics, Yet here’s a travelled man that knows What he talks about, And there’s a politician That has both read and thought, And maybe what they say is true Of war and war’s alarms, But O that I were young again And held her in my arms.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2023 World edition.