By now, you’ve probably heard about Amazon’s new mega-series, aka “Jeff Bezos’s answer to Game of Thrones.” There is probably no property more beloved in fantasy circles than JRR Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, superbly filmed by Peter Jackson at the beginning of the millennium. But Hollywood — and its latest cousin, streaming television — finds itself unable to let go where there is the prospect of a hit. So first we had the endlessly protracted and deeply boring Hobbit series, and now we have Amazon’s new venture into Tolkien’s universe, the grandiosely titled Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power.

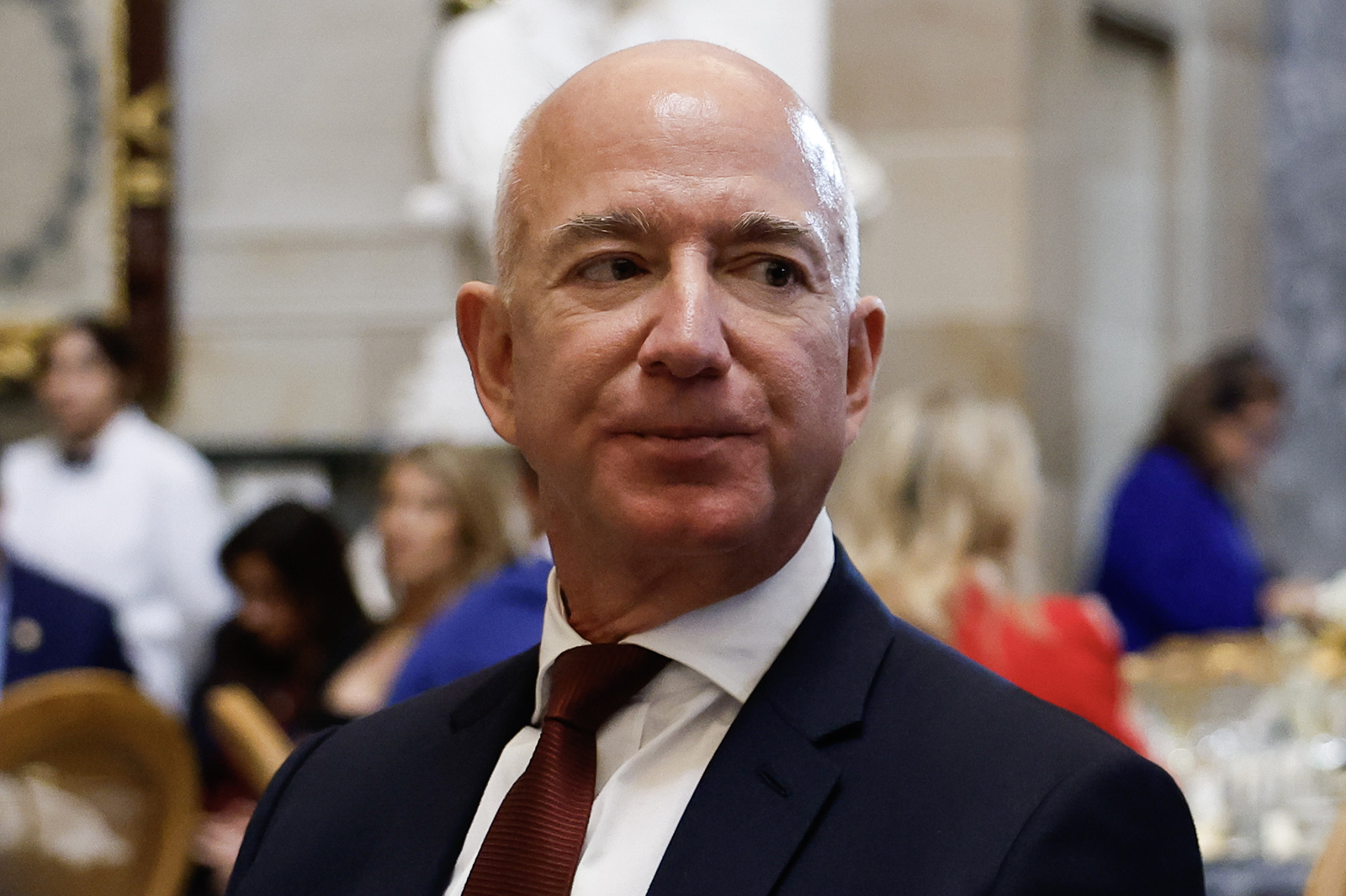

Budgeted at a staggering $465 million, and without any A-list cast members (though featuring such distinguished British character actors as Lenny Henry, Charles Edwards and Peter Mullan), it is clear that this is an attempt not just to create a series that will rival the Jackson trilogy and Game of Thrones, but to surpass them. After the relative failure of Amazon’s much-hyped Robert Jordan adaptation The Wheel of Time, the pressure is on to produce a hit that will not only establish the service as a competitor to the beleaguered Netflix and emergent Disney+, but will drive revenue (Amazon Prime, coincidentally or not, recently announced its first price increase for an annual subscription since 2018, up to $139 a year).

For those millions of Tolkien aficionados who are committed to seeing their beloved universe brought to life once again, this will be a price worth paying for the show alone. For others, who may have enjoyed both Tolkien’s original books and the first Lord of the Rings trilogy, it might be a harder sell. The first teaser trailer for the show was greeted with a mixture of disappointment and ridicule — “where’s the money gone” was a phrase used more than once. And although subsequent marketing material has been more sure-footed, it is difficult to escape the sense that an awful lot of cash and effort has gone into a show that will ultimately represent an expensive exercise in marginalia.

A phrase often used about Tolkien’s posthumously published work, which began with the appearance of The Silmarillion in 1977, four years after his death in 1973, is “fragmentary material.” This is a polite way of saying that the twenty-odd books that have appeared over the past few decades, mostly edited and compiled by Tolkien’s son (and literary executor) Christopher, are less a coherent expression of the author’s wishes and more a gussied-up extrapolation of old notebooks and half-finished scraps. It would not have come as much of a surprise to find Tolkien’s school essays reverently edited and sold as “the origins of Lord of the Rings.”

Which is more or less what The Rings of Power has done. While similar accusations can be leveled at HBO’s Game of Thrones preview series House of the Dragon, at least that was made with the involvement of the books’ creator, George RR Martin, and serves the tacit purpose of erasing memories of the dire final series of Thrones. There is no doubt that the new Lord of the Rings show is going to attract a vast amount of interest and attention, thanks in part to its unlimited marketing budget. But you have to ask whether this exercise in artistic necrophilia represents anything other than one of the world’s wealthiest men demanding a resolution to his childhood fantasies.

Tolkien, a notably modest and retiring man, would, one fears, have turned in his grave to see what his legacy has become.