In 1876, writing to his friend Gertrude Tennant, Gustave Flaubert set down a principle that artists and writers should live by: Soyez réglé dans votre vie et ordinaire comme un bourgeois, afin d’être violent et original dans vos œuvres. (Be regular in your life and ordinary as a bourgeois, in order to be violent and original in your work.)

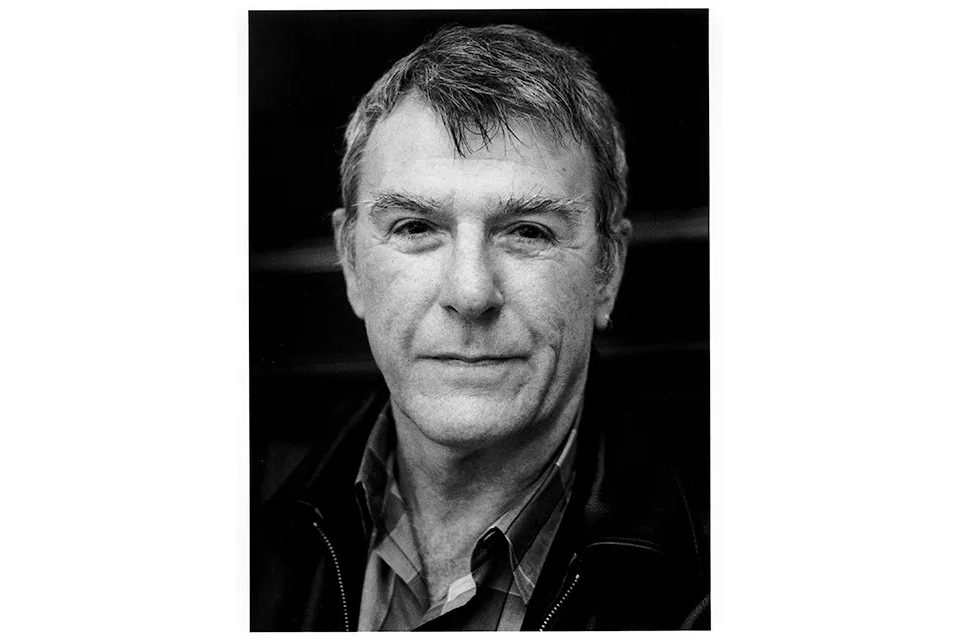

The life of the English poet Thom Gunn had its disciplined aspect (he managed to hold down a job at least), but, overall, it was so dedicated to debauchery and excess that it’s a wonder it lasted as long as it did. The story, told in detail by Michael Nott, makes even the least censorious reader sometimes wonder why this seemed like a good idea.

Gunn was born in Kent in 1929 to an upper-middle-class intellectual family. (At one point they sold their house in Frognal, London, to Penelope Fitzgerald’s father E.V. Knox.) His own father was an important journalist and newspaper executive. His parents divorced and remarried. When his stepfather in turn left his mother, she committed suicide. Gunn and his younger brother, both in their early teens, discovered her body.

Quite soon, Gunn said, AIDS stopped affecting him because almost everybody he knew had died of it

At the University of Cambridge, Gunn fell in love with a number of men, including a visiting American called Mike Kitay. When Mike returned to America, Thom went with him. At first, in the mid-1950s, they were discreet. Mike was serving in the military and came under investigation; Thom was by then a published poet, often grouped with others of a brilliant generation such as Ted Hughes. What he found most appealing in San Francisco was the nascent gay leather scene, obsessed with James Dean and Marlon Brando, acting out taciturn manliness, often venturing into recreational whips and chains.

This was a time of sexual promiscuity, and in less than a decade Mike and Thom’s relationship had become sexless. Mike fell in love serially, with individuals; Thom was more of a guy for “tricks” and “trade,” in the terms of the day — casual pick-ups and sex with strangers in bars and clubs. The names of these places are wonderfully period now — the Ramrod, Boot Camp, the Why Not?, the Hole in the Wall (from which Thom was eventually barred for bad behavior). Some of his new acquaintances stuck, and quite soon his house became home to a number of men, almost all of whom had butched their names down to monosyllables. It’s sometimes hard to work out who was having sex with whom in the “family,” but I expect it was the same at the time:

Although Don spent most of his visit in bed, Thom was still grateful for his company. Mike and Bob had rented a cabin for the summer on the Russian River; Bill and Jim hid themselves away to smoke PCP.

The distinguished poetic career continued, with an evidently successful teaching job at a university. The poetry started to cover Thom’s weekend excesses more overtly, but the two worlds he inhabited only occasionally overlapped. I kept wondering what a visiting academic friend, Tony Tanner, made of a friend called Clint Cline hanging around for sex and drugs. Sometimes the overlap threatened disaster. On a visit to London, Thom’s publisher Charles Monteith took him to the Travellers for lunch. He found he’d risked expulsion from the club after his guest appeared wearing full leather fetish gear.

San Francisco was at the center of hedonistic discovery, continuing despite the casualties. When HIV struck in 1981, Thom’s circle was at the center of the catastrophe, too. He knew some of the very first recorded victims. His sexual practices, though liberally bestowed on half the neighborhood for decades, were not those which most efficiently transmitted the virus. Gunn was clear. He remained an observer, as dozens of his closest friends died in rapid succession, recording it in his much-admired collection The Man With Night Sweats. Quite soon, he said, HIV stopped affecting him because almost everybody he knew had died of it.

On he went. By the late 1990s, to the rest of the gay community he was a perfect museum piece, his wardrobe straight out of 1960s Tom of Finland drawings. As people who once had huge sexual success find, it is traumatic when it deserts them in time. But Thom had a solution: “He developed other ways of finding sex: namely by offering guys drugs to get them to go home with him.”

It must have occurred even to Gunn that this was not a very good idea and the men attracted by an offer of this sort from a pensioner might not be the best company in other respects. “A strange night,” Thom writes in his diary. “I end up smoking crack with someone called Allen on the street.” Other boys are commended because they are really good at injecting Thom with amphetamines. The pleasures are quite hard to understand. Nott writes:

The highlight of Thom’s summer was ‘an exquisite holiday,’ a four-day trip to Los Angeles with Robert Gallegos, now a good friend. They stayed at Coral Sands, a famously cruisy motel where ‘everyone was on crystal.’ They pooled their speed and went to Long Beach to buy more. By the third day, Thom was ‘hallucinating magnolia bushes as Bosnian refugees with their luggage…’ It was all ‘drugs and brittle fun… swimming pools and frivolity’

Even the family of Bob and Bill and Mike and so on were getting fed up with the “frivolity.” In reality, this meant a parade of homeless drug addicts through Thom’s bedroom, putting up with the sex in exchange for a gram of speed and the chance to steal some stuff. Thom was quite a gruesome spectacle by now, his dedication to wearing leather at all times unaffected by age and decrepitude. Mike, still around in quite a saintly way, observing Thom’s breakfast ensemble, said cattily it was a wonder that he didn’t wear leather underwear.

It ended in a predictable way for a seventy-five-year-old promiscuous drug user with high blood pressure. A homeless man came home with him, injected himself and Thom with a cocktail of drugs, and scarpered, leaving a member of the family to discover Thom’s body on his bedroom floor. A cautionary tale, one might say, except that very few of us would ever possess anything like the energy to begin to emulate it.

The poetry certainly has merit. Gunn was dedicated to the Elizabethan lyric, and much of his best work is beautifully formal, whatever the subject. He was a good phrasemaker, though sometimes the gap between an educated English voice and the thing described is a little wide. It is curious that his leather-biker-fetish poem “On the Move” concludes in the schoolmasterly “One is always…” Free verse comes in, and syllabics, sometimes well handled, sometimes not. His best book is Moly, about magical transformations, myth, lyric and (largely allusively) the first ecstatic wave of Californian free love. The Man With Night Sweats was and is much praised for the gravity of its subject, but it must be said that some of its poetry, such as the extended “Lament” in rhyming couplets, is quite embarrassing.

This is a very thorough life, well documented and with a proper backing of interviews with people who knew Gunn over decades. I suspect more of the playmates of his later years might be tracked down, but I wouldn’t envy the biographer’s task of getting useful information out of them. Nott rightly draws attention to the fact that Gunn paid hardly any attention to women — like some homosexuals of his generation, half the human race meant so little to him that he didn’t even venture into routine misogyny.

Michael Nott’s Thom Gunn: A Cool Queer Life tells Gunn’s story in borderline-grueling detail. Sometimes I felt that the narrative had skimped on the lives of those close to him, so that occasionally one had to deduce that a housemate had come through an HIV diagnosis or developed a crack addiction since their previous appearance. But on the whole it will do very well. In the end, Gunn left a trace on the grass, like the snail in one of his best poems — but unlike Phil Monsky, the Speed Brothers Eric and Rick, Randy Glaser, Allan Noseworthy III, Clint Cline and a guy named Chuck, all lost to the streets, dead in what should have been their prime, abandoned in the memories of people themselves long forgotten.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply