In the mid-1950s, alongside his close friend and intimate confidant John Coltrane, the revered saxophonist Sonny Rollins completely revolutionized notions about how the tenor saxophone could function within modern jazz. In landmark albums like Freedom Suite, Way Out West and Tenor Madness, Rollins pushed the art of melodic improvisation to transcendent new heights, his charismatic sound, his snaking melodies and his rhythmic liquidity ringing the changes as surely as Louis Armstrong had done thirty years earlier.

And like Louis, and later Miles Davis, there came a point where Rollins wrestled free of the jazz aficionado’s gaze to become admired by a more general audience. He put in a cameo appearance on the Rolling Stones’ album Tattoo You in 1981 and has remained an essential point of departure for new stars of the instrument, like Shabaka Hutchings and also Kendrick Lamar’s saxophonist of choice, Kamasi Washington.

Now aged ninety-three and retired from performance since 2012 due to a lung condition, Rollins keeps a kindly, but definitely steely, eye on a musical scene he once dominated. When he donated his archive to the New York Public Library in 2017, his personal journals occupied what the editor of this new volume, Sam V.H. Reese, describes as “a hefty six boxes,” and The Notebooks of Sonny Rollins turns out to be a distillation of that material, presented as a bricolage of thoughts and ideas designed to coalesce into a mind-map of Rollins’s thinking from the late 1950s, when famously he vanished from the jazz scene for three years, to today.

Rollins kept returning to the possibility of documenting his thoughts about music and other spin-off ideas inside a book, which he variously considered titling Fantastic Saxophone, The Fraternity of Saxophone or The Saxophone Brotherhood, but it was a project that proved beyond him. Here are the workings-out for that never-completed book, scattered over 150 pages, sometimes with text arranged in dense clumps, others with aphoristic thoughts marooned in white space as though in a poem by e. e. cummings. Implicit in its publication is the admission that Rollins will now never complete his book as intended — but perhaps he was never temperamentally suited to taking a settled view on something as mercurial as improvised music, to fixing ideas between two covers.

The book opens in 1959, a year often celebrated as a milestone in the development of modern jazz — when Coltrane (Giant Steps), Miles Davis (Kind of Blue), Charles Mingus (Mingus Ah Um), Dave Brubeck (Time Out) and Ornette Coleman (The Shape of Jazz To Come) all delivered game-changing albums — artistic highs tempered by the miserably premature deaths of the tenor saxophonist Lester Young, a formative influence on the young Rollins, and of Billie Holiday. Rollins, though, was feeling burned out, and disappeared into the night following a highly successful European tour, during which he had been feted as the pre-eminent modern jazz hero. The three-year sabbatical that followed was, initially, about finding a way of reinventing his approach to the saxophone and toward improvisation; and it was during this period that his obsessive notetaking began, with topics including music, politics and spirituality. His performing career on hold, Rollins clearly needed another outlet for the thoughts that were crowding his brain.

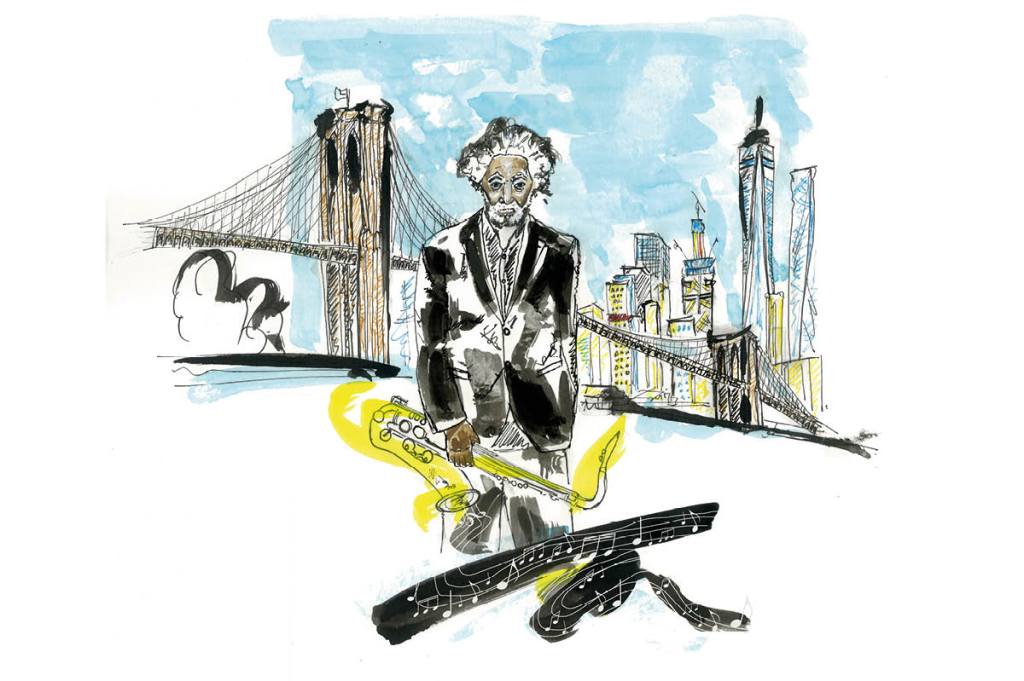

The mythology is even more dramatic because he quite literally disappeared into the night. Finding his apartment acoustically unsuitable to rituals of saxophone practice (and just think of the poor neighbors), he took to practicing underneath the main structure of the Williamsburg Bridge in New York City, hunkering down inside an alcove where he could be overheard but not easily seen and therefore disturbed. These practice sessions extended over many hours, and occasionally he put in all-nighters. Once he returned to active performance in 1961, the next year’s comeback album was inevitably called The Bridge. The mythomania surrounding him, those restless nocturnal wanderings, the lone genius finding his art again by improvising to the sound of the city, set concrete-hard. Unlike Coltrane, whose every album from Africa Brass to A Love Supreme and beyond marked the realization of yet another striking new way of conceptualizing improvisation, The Bridge proved disappointing to many. After three years of self-improvement, was this selection of largely standard tunes, climaxing with Cole Porter’s “You Do Something To Me,” really state-of-the-art material? Reese speculates that Rollins’s sabbatical has long been misunderstood. In fact, it was never about reaching into the cosmos to find fresh concepts destined to change eve- rything. On the contrary, as jazz was becoming increasingly conceptual, Rollins was concerned that too many musicians were neglecting the basics. His goal was not revolution — he was motivated to achieve complete technical “mastership.”

The extent to which Rollins obsessed over the tiniest of technical details on his saxophone runs through the book. One minuscule finger movement could be enough to alter the resonance of a particular note either radically or indeed so faintly you’d need the ears of a bat to perceive it — and Rollins was open to both. This extended to his pushing his instrument beyond where recognized technique could function, to a point where the instrument operated but only in theory. Experimenting with bouncing the same note between different octaves, he described “higher notes that I have not figured out yet,” then scheduled time to explore beyond where his instrument normally sounded. Perhaps he could locate those notes, perhaps he couldn’t, but it was the endeavor that mattered.

Early in the book another theme emerges: his regret at the lowly lot of the jazz musician. All these decades later, figures like Rollins and Coltrane have become icons, but back in the day “the working conditions of many great jazz musicians are very, very far… below par!” he mourns. Making transcendent art in nightclubs, which were operated largely by shady characters “closely associated with underworld elements,” created inescapable tensions between goals of artistic purity and the brutal economic truth that jazz clubs, for the mob, were all about making money, exercising control and selling drugs.

Rollins’s high ideals rubbed uncomfortably against reality. Jazz, he explains, is “the music of America created by Americans for the edification of all of mankind.” As with many musicians, including Duke Ellington and Miles Davis, the word “jazz” became a bugbear to him, a label used, often cynically, to hold the ambitions of black musicians at bay, to retain them as “entertainers” — to put clear boundaries between black culture and the great Western tradition of Bach and Beethoven.

Rollins is clear that “mustn’t we start speaking of MUSIC and not jazz.” This music was “All American.” And although it’s of black origin, care must be taken “not to synonymize Negro and Jazz and not depict Jazz as a Negro product.” As Rollins unpicks the techniques of Indian music, you realize how deeply he believed that jazz also needed to reach out beyond America itself.

Although in his introduction Reese provides a historical overview, the book might have benefited from more detailed annotation, a smattering of anchors and markers for the benefit of those less familiar with the Rollins story. Aidan Levy’s exhaustively detailed biography Saxophone Colossus: The Life and Music of Sonny Rollins, published last year, is the place to go for that backstory, from which Reese might have pulled details about the time Rollins spent studying with a guru in India, which would clarify how his jazz incorporated music from other cultures. Approaching the final pages, as Rollins introduces a character called Lucille, readers who don’t know that she was his wife and later manager, who died in 2004, might struggle to understand the significance of his musings about resuming performing afterward.

Another curious omission is any meaningful reference to Rollins’s struggles with drug addiction early in his career and his long road back from near self-destruction. His words are filled with the shame he feels over his tobacco habit: how tempting he finds smoking, how wretched cigarettes make him feel, how badly they affect the chemistry of his playing. “Nature take me back, I am yours,” he proclaims, in a line dropped into the middle of a discussion about saxophone technique, and his quest to become one with his saxophone is reflected in his concerns, environmental and cultural, for the planet. Corporate greed, rabid commercialism and ecological ruin disgust him, and the “problem with our system is that it best rewards the worst part of us,” he concludes.

He writes to Bill Clinton and Michelle Obama to garner their support for his Jazz Masters program, designed to proselytize the benefits of jazz’s “strength, beauty and moral spirituality.” His belief that music — improvised music in particular — is imbued with powers that can reconnect those who take it seriously with fundamental good is highly unfashionable these days, but there’s nothing wrong with that. Even if jazz has developed stylistically in ways Rollins might not have foreseen, its founding attitudes — toward musicians working collectively, toward keeping an open mind to the lessons of music from other cultures — are enduring. “Jazz music is not a fad,” he tells the former first lady. “It has no beginning and it has no endings” — an attitude mirrored in this enlightening book.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply