Book reviews should be like Car & Driver: flip over the page to a concrete, plainly written piece — no writerly words or literary drivel — by someone who’s test-driven the book and punched up a nuts-and-bolts guide. The reader should get a look under the hood: polished steel and chrome cylinders. Does it hum? Vroom, we’re off the races.

I say this because I’m reporting on a prototype I’m afraid of driving: an advance reader’s edition, uncorrected, not for sale or quotation. I can’t rev this baby for you, or even kick the tires, but here goes.

Let me give you the technical details: Abraham Riesman’s Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America is 356 pages of tightly packed, unauthorized biography; with eighty pages of notes to support its extensive reporting on Vince McMahon: the most influential pro-wrestling promoter of all time, P.T. Barnum with a steel chair and pugnacious strut. The body of the book — what we see before we go under the hood — is a straightforward account of McMahon’s rise from white-trash, sexually-abused juvenile delinquent (who mythologized his past) into what he himself describes as “the Walt Disney of pro wrestling.” Along the way, Riesman’s reporting challenges McMahon’s creation myth, in particular Vince Jr.’s romanticization of Vince Sr., the beloved promoter who sold him the WWF in 1982.

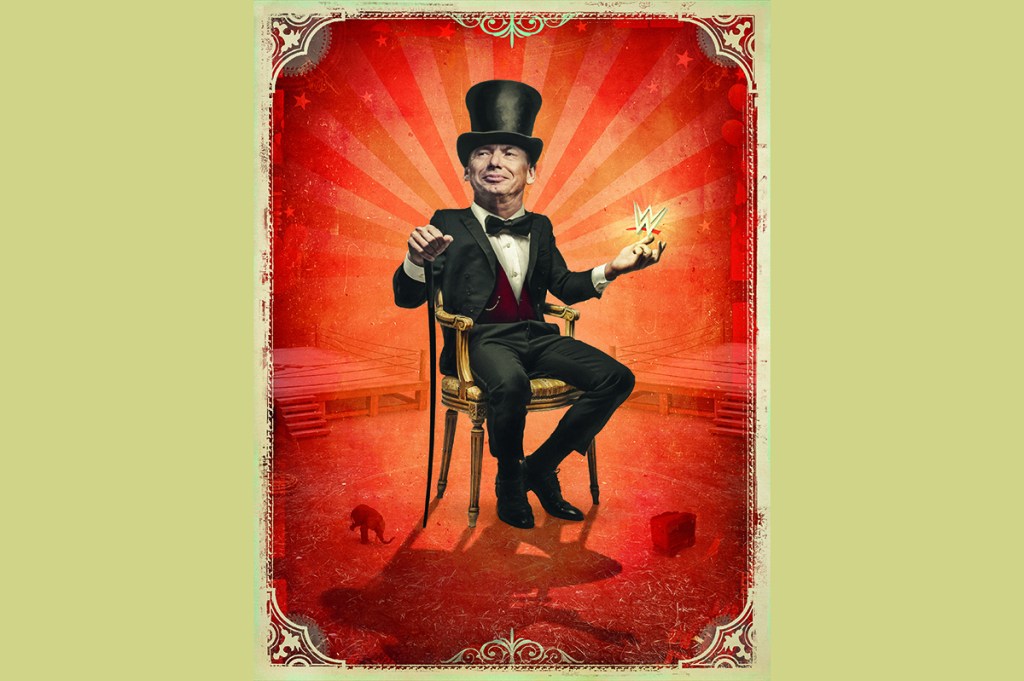

But this book is not just about Vince McMahon, ringmaster. It’s about his circus of abused elephants, magicians, bearded ladies who refuse to give up their spots (The Fabulous Moolah), musclemen dipped in bleach (Hulk Hogan), clowns, acrobats who fall to their deaths — the show must go on! — a “family business” turned into the bloodiest version of Succession; and how McMahon, like Barnum before him, gobbled up his competition, buried scandal after scandal and declared his version of wrestling “sports entertainment,” rechristening the outlandish ballyhoo of pro wrestling for consumption by a mass audience.

Ringmaster itself is written for a mass audience, a too-rare approach which should be applauded. It is a pro-wrestling bio written like a treatment for an episode of Dark Side of the Ring or an entry-level Netflix docuseries. Far too many pro-wrestling bios are written for “marks” (industry parlance for “hardcore fans”), but Riesman has written a book that treats its subject the way a scholar might, rather than a fan or insider. Riesman is not a wrestling reporter, or a retired wrestler or an aggrieved former employee. She is not a “mark” but a lapsed fan who long since stopped watching wrestling but understands that the WWF of the Eighties and Nineties shaped her in some way.

Not only doesn’t Riesman reflexively turn up her nose at pro wrestling, she correctly sees it as art, perhaps the most American art of all. A book on wrestling by someone skeptical about its artistic merits would be like a book on pumping iron by someone who hates the look of muscles. It’s even dedicated to Riesman’s mother, who custom-stitched her a tearaway T-shirt after they saw Hulk Hogan on TV — a cute reminder that we are all (as Riesman later suggests) children of Vince McMahon, and this is, after a fashion, a family story.

The book’s design resonates brilliantly with its subject. The cover is the color of blood on a wrestler’s forehead; its yellow WrestleMania font evokes the over the top propaganda of Hulkamania. In the foreground stands Vince McMahon (c. 1998) in a tailored Italian suit, with clenched fists and a ridiculous smirk on his face — the embodiment of what Riesman describes as pro wrestling’s uneasy marriage of camp and masculinity, and the sort of halfway jokey image you’d find illustrating a Vanity Fair article.

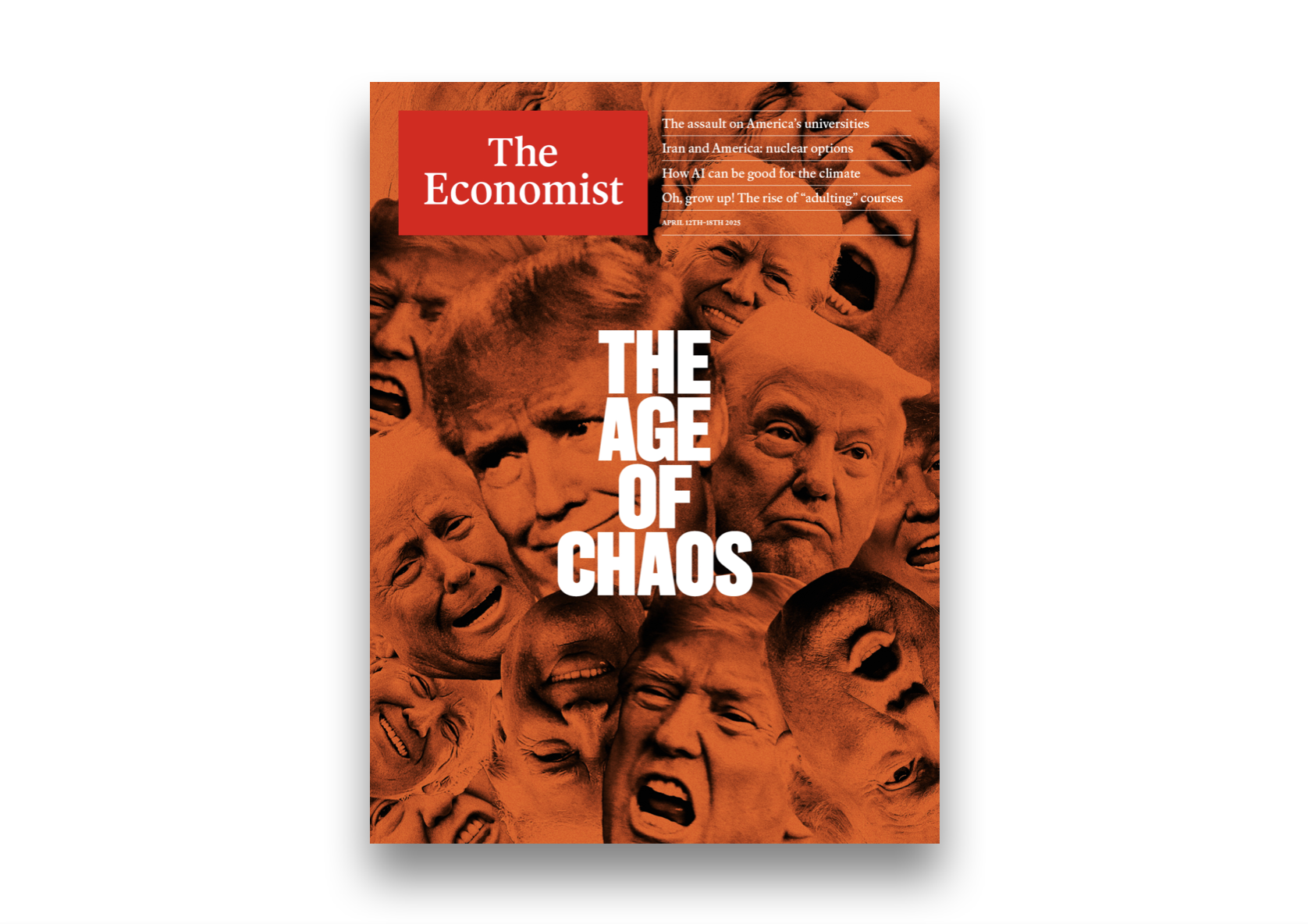

To some extent Ringmaster suggests that Vince McMahon’s smoke-and-mirrors artifice introduced the world to Trumpism. The “heat” that propels this angle is that Trumpism is a more politicized version of what Riesman calls “neokayfabe,” Vince McMahon’s corporatization of “kayfabe,” — the conceit that keeps the “secret” that pro wrestling is a staged spectacle and, of course, implicates the marks in the wink and the nod. Ringmaster argues that McMahon’s neokayfabe helped lay the groundwork for turning American politics into a bombastic, dangerously jingoistic spectacle of “alternative facts,” fueled by the type of war with the media that McMahon pioneered. Enter our first carny president: Donald Trump, as Riesman notes several times, a close personal friend of Ringmaster McMahon, wrestling’s Michelangelo, Medici, Machiavelli and Michael Bay, with basketball-sized biceps. Trump is a member of the WWE Hall of Fame: he’s been an investor in the enterprise, and in 2007 he and McMahon played “battling billionaires” backing wrestlers in a kayfabulous contest where they agreed the losing plutocrat would have his head shaved (it wasn’t Trump).

Every book about a cult subject like pro wrestling needs a mainstream hook. The only way to sell a pro wrestling book to a neo-liberal audience is to make it political, to go “beyond the mat,” to subvert the view that sees pro wrestling as white-trash entertainment like NASCAR or country music: not “American opera,” to quote music mogul Rick Rubin, a viewpoint I share, but a kind of carnival freakshow that’s not sport enough for sports fans, not theater enough for theatergoers, just “fake”; a word wrestlers from the kayfabe-era would have responded to with physical demonstrations of why it wasn’t fake. Wham! Right across the head. “Does that feel fake?” You make it political because you need to make it newsworthy.

Riesman’s reporting for this book is comprehensive. There’s research in Ringmaster accumulated from over 150 interviews, along with a family history of Vince McMahon that cuts deep into his DNA, a plethora of quotes from pro wrestling journalists like Dave Meltzer (who appears as often in this book as he does on TV during a McMahon-related scandal), interviews with wrestlers like Jake “the Snake” Roberts and Bret Hart — nobody from the McMahon family or the WWE, of course — and there’s lots of muscle behind the reporting. It is not Riesman’s soapbox or a revenge treatment of a subject who is now a #MeToo villain. It is not a moralistic book, though there’s some of that in the overture and the coda. Riesman views McMahon with equal amounts of reverence, disgust and dark humor, especially regarding WWE’s ridiculously violent and sexist “Attitude Era” (1997-2002). All this makes Riesman, whose previous foray into popular biography was a 2021 biography of Stan Lee, the perfect choice for writing a biography on a subject as completely absurd as Vince McMahon.

I marked up several pages with “LOL” and “WTF” and “Holy Shit!” and “USA! USA! USA!” as if I was at a WWE event, hysterically chanting at the cringe-camp spectacle before me. In other words, it’s a fun book.

Now for the main event: should you buy Ringmaster? If you’re vaguely interested in a ludicrously buff mogul who booked himself to beat God in a wrestling match, or just interested in a definitive book on America’s last truly riveting carny showman, this is a book that will force you to turn the page. But if you only view Vince McMahon as a Republican donor or just want to connect the dots between Trumpism and neokayfabe, it’s going to leave you feeling unsatisfied. Ringmaster certainly draws some lines between Trumpism and neokayfabe, as it should, but the gist of the book is a history of the revolutionary who is in the process of a hostile takeover of the company that ousted him last summer. The book almost needs another chapter. Riesman’s sequel could be titled Vengeance: How Vince McMahon Killed the Business. It’s a storyline that seems to have no end. The biggest tragedy of Ringmaster is that it was written before the final chapter in the story of Vince McMahon.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.