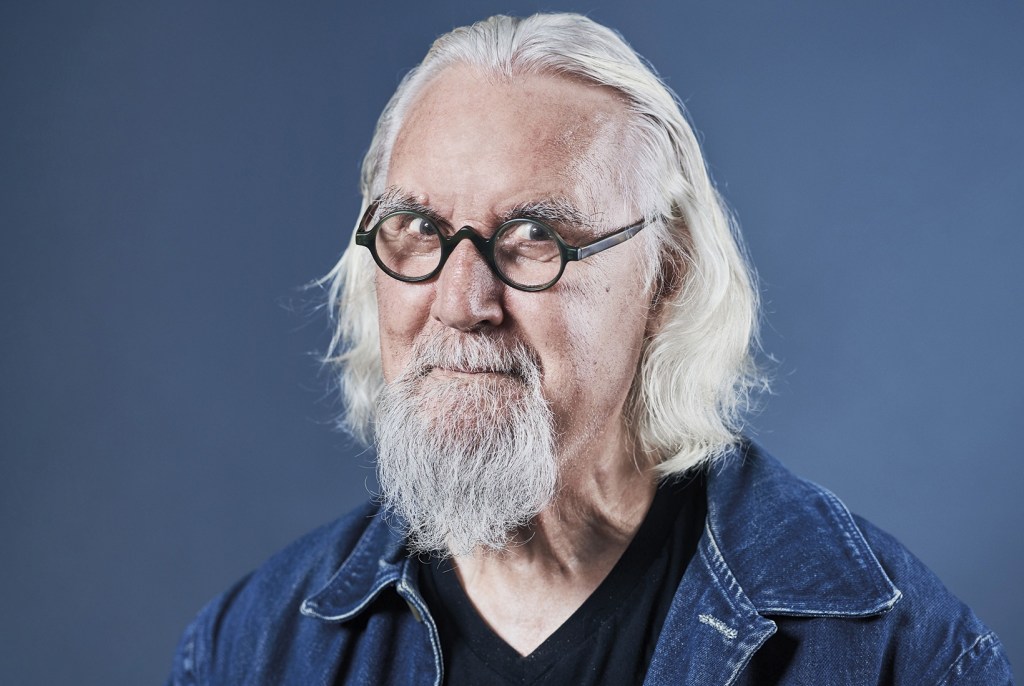

We are in a basement gallery in London’s West End, and Britain’s greatest comedian is doing what he does best — sharing his delight at the daft absurdities of daily life. He remembers seeing a little boy wading into the freezing waters at Aberdeen. ‘You make a certain noise when the wave comes up. It’s a noise that you can only repeat by shoving a hot potato up a donkey’s arse.’

He is making this empty gallery feel as though it’s full of people — and a bunch of strangers laugh like old friends. ‘A lot of my stuff doesn’t have punchlines’. He doesn’t need them. ‘It’s lovely just making a big picture, and saying, “I was there, and I’d like to invite you to share it with me.”’

Billy Connolly retired from stand-up in December 2018 and has no plans to return. The cruel culprit is Parkinson’s disease, which has inevitably restricted his spontaneous, stream-of-consciousness delivery. ‘I think differently — it’s hard to describe,’ he tells me. ‘I don’t think and move the way I used to, so I don’t want to do it in case it doesn’t work.’ In conversation he remains razor-sharp but live performance is another matter. Onstage he was running wild, never knowing where each joke would take him. ‘I didn’t compose it — it just happened. Ad lib on top of ad lib on top of ad lib and it became stories.’ Does he miss it? ‘No, I don’t miss it at all. I had plenty of it. I had my share.’

He’s here today to promote an exhibition of his drawings, paintings and sculptures that, like everything else, has now moved online. You’d never guess he made them. Onstage and in person, he’s ebullient, effervescent. These artworks are the complete opposite — enigmatic and discreet. Nobody is pretending he’ll be remembered as an artist rather than a comedian, but it’s heartening to see him feeling his way in a new genre, just as his mind and body are slowing down. ‘It’s exhilarating — I get frightened coming in here, coming down the stairs, knowing I’m going to be confronted by them on the wall.’

He never intended to exhibit them. ‘It was all done behind my back — my manager sent them to the gallery. I was terrified I’d be found pretentious. You know, you get the actor who’s retired and now paints a little, because nobody’ll fucking talk to him!’ Of course they’re a bit hit and miss, like the work of any fledgling artist, but they’re sincere and original, and who cares if they don’t set the art world alight? He’s been pleasing us for 50 years. He’s earned the right to please himself.

He’s always had a love of art. Growing up in Glasgow, he loved going to Kelvingrove with his sister to gaze at Salvador Dali’s ‘Christ of St John of the Cross’. ‘I used to visit it like a relative.’ He loved the building too. ‘We used to go for a slide. They had marble floors and you took your shoes off and slid in your socks.’ In his early days as a comic he was renowned for his outlandish, stylish costumes. He fronted a super TV show about the history of Scottish art. ‘It said so much about Scotland that had never been said before,’ he recalls. ‘There are great artists in Scotland, and they were always second in the queue behind England, behind London.’ His intimate, insightful TV travelogues include numerous encounters with artists — some well-known, some less so. He treats everyone the same. He collects the art he likes.

His life story is so familiar, it’s become a kind of fable: born in 1942 in Glasgow, raised by two fiery aunts when his mum went away; the camaraderie of the Clydeside shipyards, where he worked as a welder; his spectacular rise to stardom; his marriage to Pamela Stephenson…was it nature or nurture that shaped his talent, I wonder. Glasgow and the shipyards gave him something special — the oral tradition, the sectarian tension, the fierce and friendly humor — but a lot of folk grew up that way and only one of them became Billy Connolly.

‘I like Glasgow very much,’ he says. ‘It’s in a constant state of change.’ Only the people remain the same. ‘It’s a funny thing. Where I was born and spent the first four-and-half years of my life was hell. It was down at the docks. It was everything that was wrong with Glasgow. And now it’s an incredibly fashionable restaurant area, which is kinda strange but kinda nice…’

His childhood was a challenge — an absent mother, an abusive father, the teachers who tormented him. ‘I find it difficult to forgive them — to take a little boy’s life and fuck around with it like that. It’s unfair.’ Yet he emerged with a lust for life and a thirst for knowledge. ‘I hear people saying that football is the escape for the working class, or rock ’n’ roll is the escape for the working class. I was always thinking, “No it’s not — the library is the escape. That’s where the tunnel is.” You’ve access to the great brains of the world, and it’s free.’

His first foray into showbusiness was playing the banjo on the British folk circuit. ‘It was the life on the road I was aiming for — it wasn’t the fame. I wanted to be on the road like all the great guys: Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, Hank Williams…’ If he’d been a cool guitarist it might have been a different story. ‘The desire to be a banjo player made me stand out because nobody else wanted to be one. There used to be a joke — the one line you never hear when musicians meet: “She’s fucking the banjo player!”’

His comedy grew organically, out of the banter between the songs. ‘I was in Australia, and I packed the gear and went to the gig — and there was no banjo. I’d forgotten to pack it and I had to go on without it.’ It was the first time he’d performed without it. ‘I couldn’t reach for it and it scared me. And I went on and I did it and it was a huge success. Then I came back and I was in Forfar, in Scotland, and I had it at the side of the stage so I could see it.’ He didn’t need it. From then on, he gigged without it. He never looked back.

The other thing he ditched that night was the mike stand. He’d always painted amazingly vivid word pictures, but the mike stand had kept him rooted to the spot. Now he could roam around the stage, acting out his routines, interacting with his audience. ‘It made a huge difference,’ he says. ‘It suddenly let me off the leash. I became Billy Connolly. I started to do funny moves, funny walks.’ He became a brilliant mime, and also a fine actor — a parallel career that reached its peak with his starring role in Mrs Brown, opposite Judi Dench as Queen Victoria.

In the end, his comedy became entirely naturalistic — as natural as a group of mates laughing in the pub. ‘That’s been my driving force for years,’ he says. ‘I always said, “That’s what I want to be — somebody who’s funny, just for the sake of it, to make your friends laugh for no apparent reason at all.”’ There was no script. His only prop was a simple set list, which he left on a bar stool and sneaked a glance at when he stopped for a sip of water. ‘It wasn’t sections of an act, it was just one-liners.’

He’s still makes TV documentaries, with the same free-flowing, improvisational style of his stand-up. ‘Everything’s one take — nothing’s written,’ he says. ‘It’s a very live performance.’ He recently returned to Glasgow to make a film for the BBC about his roots. ‘Going to the shipyards and going to the pubs I used to go to was a joy to do,’ he says. ‘It wasn’t about how much I like Glasgow. It was about how well Glasgow knows me. There was a man crying. He came up and he went, “Billy! How great to see you!” And he gave me a cuddle.’

It happens to him a lot. Strangers feel they know him because he’s always revealed so much of himself, not just the fun times but the bad times too. ‘If you’re gonna be good you’re gonna have to talk about it, you’re gonna have to share it with people — even if it’s just a feeling you’re sharing with people, you’re gonna have to unleash it and say, “This is what I am.”’ His career has been a kind of autobiography, a life-enhancing story we’ve been following for half a century. And though the stand-up part is over, it’s good to know there are other chapters still to come.

The drawings, paintings and sculptures from Billy Connolly’s exhibition

Born on a Rainy Day are available to view and buy online at www.castlefineart.com. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.