A commercial publisher bringing out a book of old academic essays on Austrian writers, some completely unknown to English readers, might need an explanation. In this case the author is W.G. Sebald, who produced a series of cogitative books that made his name in the 1990s. Before he acquired the worldwide authority of The Emigrants, The Rings of Saturn and Austerlitz, Sebald had a career in the academic proponency of German literature. Silent Catastrophes is the first English translation of two essay collections from 1985 and 1991, The Description of Misfortune and Strange Homeland. (“Uncanny” would be a better translation than “strange,” but neither title goes easily into English.)

It is fair to warn fans of Sebald’s distinctive manner of lucidly depressed observation that much of this is in the familiar mandarin mock-philosophy style of 1980s literary criticism:

It is perhaps only now that we can grasp the full implications of his theory, in following, for example, Gregory Bateson’s theories on the subject of aesthetics-evolution-epistemology, according to which the successive loss of our ‘natural’ affinity with aesthetic structures is described as an epistemological ‘mistake’ whose consequences cannot yet be guessed at.

We can grasp the full implications, but at the same time the consequences cannot yet be guessed at. I don’t think we need bother.

The Austrian novel is one of the most interesting traditions in Europe. Sebald wasn’t part of it; he grew up in Bavaria, on the other side of the border, an early lesson in the temptations of exile that led him to East Anglia. These essays cover a good number of the most significant figures, including Franz Kafka, Joseph Roth and Thomas Bernhard, but by no means all. There is no discussion of any woman writer, nor of Robert Musil, the author of The Man Without Qualities; and the now fashionable Stefan Zweig is ignored. Sebald admired Musil, but, like many Germans with classical literary values, he may not have found Zweig worth his attention.

Significant developments since the essays were written have left some of Sebald’s comments behind. We might like to be reminded that Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle, a fairly obscure work in the 1980s, is now one of the best-known narratives in Austrian literature since Stanley Kubrick filmed it as Eyes Wide Shut. Sebald’s remarks on Peter Handke’s strenuous attempts from the start to insert his writings into a grandly canonic position as classics cast a certain light on his own ambitious career. It might be more interesting to contemplate the unfortunate public comments that did for Handke’s career. The twenty-first-century relationship between cancellation, approved behavior and canonic standing makes Sebald’s concerns look quaint.

Sebald is attracted by the less familiar works of celebrated writers – Leopold von Sacher-Masoch is here not for Venus in Furs but the sketches of Jewish life. And he wants to hold up unfinished works for our attention, including Hermann Broch’s Bergroman and Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Andreas. Both Hofmannsthal and another of Sebald’s writers, Peter Altenberg, are probably more familiar to us through composers who set their works to music – Richard Strauss in the case of Hofmannsthal’s librettos and Alban Berg’s celebrated Altenberglieder.

Sebald also likes renegade authors who fled Austria and changed their names – the nineteenth-century Karl Postl, who ran away to America and called himself Charles Sealsfield; and Jean Améry, born Hans Meyer, who renounced Austria after the Anschluss. The essays on all of these are not bad, exactly, but I would have welcomed a plainer account of the facts before plunging into exegesis through philosophical abstractions.

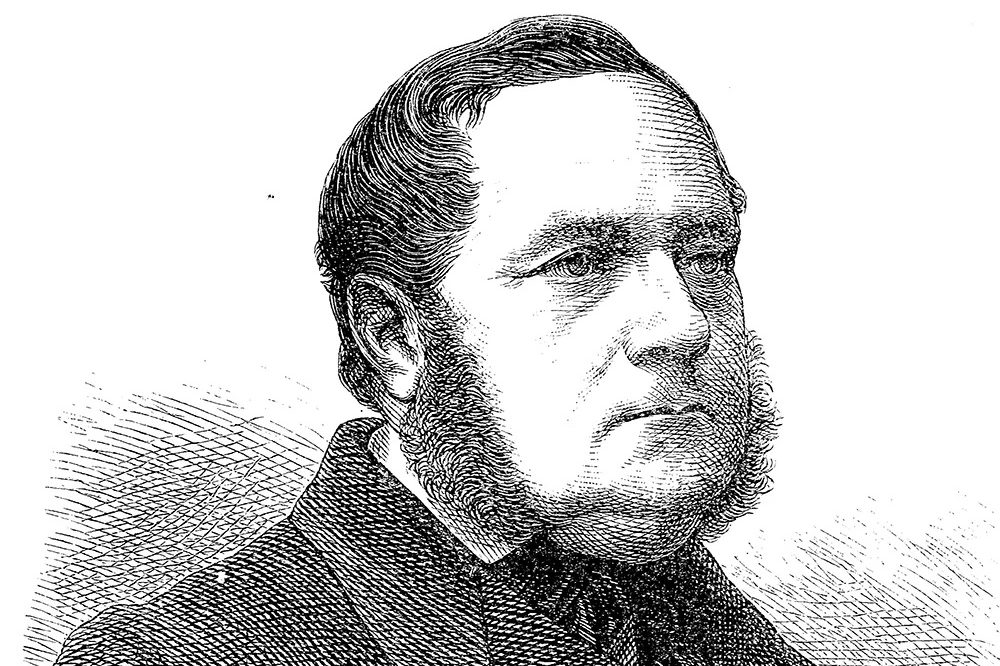

The nineteenth-century novelist Adalbert Stifter comes up repeatedly and now obsesses me. He wrote German of an astonishingly pure beauty – Sebald responds to authors, such as Roth, who write with classical elegance. Stifter’s stories have a geometrical rigor (“Der Fromme Spruch,” “The Pious Saying,” is a demented diagram in which all the characters are either called Dietwin or Gerlint). His major novels, Indian Summer and Witiko are so astonishingly dull that their technique demands to be examined. You have no idea how boring a novel can be until you reach the 400th page of Indian Summer. Such tediousness takes real dedication to craft.

Sebald supplies the (to me) new information that Stifter was grossly gluttonous, thinking nothing of polishing off two roast ducks at a go or, in convalescence, relying on “beef, baked kid, roast chicken, grouse, pigeon, veal, ham, liver with onions, roast pork, sardines, paprika chicken, baked lamb and partridge…” The list goes on. I wish I could be confident that Sebald saw how funny Stifter’s awful diet was; but at least he thought it worth recording.

Such illuminating insights are to be found here and Sebald was to become a keen observer of the individual. At this early stage of expression, however, they still have to be plucked from the academic mulch.

Leave a Reply