The medieval trope that Jews are inherently bloodthirsty has echoed down the ages. Forms of the blood libel have been disseminated ever since the myth emerged in England in the twelfth century with claims that Christian children were being ritually murdered by Jews in re-enactments of the crucifixion of Jesus. In the aftermath of October 7, Labour’s Rochdale by-election candidate Azhar Ali accused Israel of lowering its defenses so that it could justify the shedding of innocent Palestinian blood. Gigi Hadid, the American model, shared a video which alleged that Israel is harvesting the organs of Palestinians. The International Criminal Court’s pursuit of arrest warrants for Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the defense minister Yoav Gallant amid claims of genocide has been denounced by Israel’s UN ambassador Gilad Erdan and others as another manifestation of the ancient slander.

The original blood libel materialized after the First Crusade (1096-99), a turning point for Jews in Europe as a wave of religious frenzy swept communities away. Jews ritually murdered their own children in the Rhineland to prevent forced conversions. A Jewish account tells the story of Rachel of Mainz, who turned a knife on her four children before the crusaders could batter down her door. While earlier interreligious interaction was characterized by trade, the First Crusade transformed the Jews into a pressing danger.

It was said that Jews poisoned wells to spread the plague during the Black Death

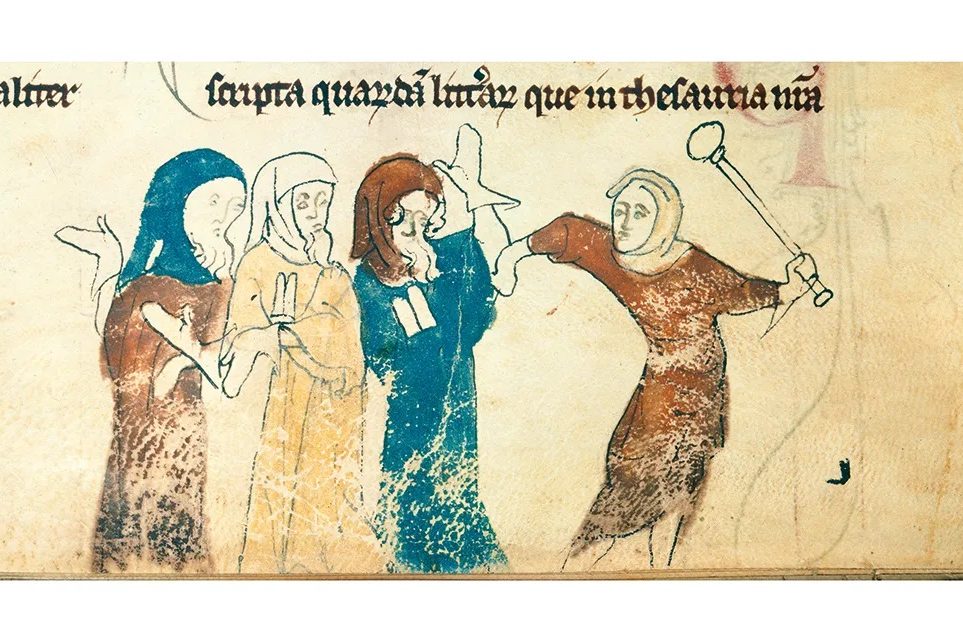

From the twelfth century on, European Christians made a range of outlandish allegations against their Jewish neighbors. As well as ritual murder and blood libel claims, Jews were accused of committing violence upon stolen consecrated hosts. It was said that Jews poisoned wells to spread the plague during the Black Death. Underpinning such charges was the belief that all Jews were “Christ-killers” and collectively responsible for deicide. The medieval Church may have condemned the blood libel and attacks on Jews, but this didn’t prevent pogroms and expulsions. Politics and finance played a significant role. The cult of the blood libel “martyr” Hugh of Lincoln (1246-55), the boy whose death was falsely attributed to Jews, flourished with royal approval from Edward I at the end of the thirteenth century in the context of the 1290 expulsion of the Jews from England, while Philip IV of France appropriated Jewish property and loans when he cast them out in 1306 amid money troubles.

There is a debate among historians over whether medieval Jew hatred contributed to modern forms of antisemitism (a word which emerged in the late nineteenth century) which culminated in the Holocaust. Hannah Arendt held that medieval and modern Jew hatred are fundamentally different because of the significant change in religious context. Others point to common and longstanding antisemitic stereotypes, such as physical deformity and usurious greed, as the key connection between the periods.

In How the West Became Antisemitic, Ivan G. Marcus argues that “a focus on stereotypes risks anachronism.” His riveting book, which concentrates on Ashkenaz (northern France, England and Germany), takes a structural approach to link medieval and modern antisemitism. Marcus thinks that medieval hatred has had long-lasting consequences through modern reinterpretations of “the binary of inverted hierarchy” (medieval Christians and Jews thought the other group should be subordinate), the idea of the Jew as an internal enemy, and the concept of Jewish identity as unchangeable. To reach this conclusion, he challenges the widely held view of the medieval Jew as a passive victim and the most interesting sections in his book examine how Jews actively asserted themselves in the face of what they considered Christian idolatry. This stirred up Christian opposition towards them and gave them a more defined presence in European society.

Jewish assertiveness took some surprising, and in some cases smelly, forms. Marcus sets out the evidence for Jews using flatulence as a means of disrespecting Christian symbols at the time of the First Crusade. He recounts the story of Asher and Meir, who turned their backs on the cross in Trier and farted before being put to the sword. Christian statues were placed in toilets. Synagogues were built higher than churches and Jewish worship wasn’t toned down. In business contracts with their Latin-reading contemporaries, Jews wrote offensive things about Christianity in Hebrew. A new eucharist-like ritual, in which youths ate cakes and eggs inscribed with passages from the Torah, was created by pietist Jews to discourage conversion. Through an adroit selection of sources, both Jewish and Christian, Marcus brings the subject matter to life.

Medieval Europe created what Marcus calls “the imagined Jew.” While Jews were assertive, there was a limit, and even after they had been expelled fantastical myths and deep-seated hatreds continued. Some of England’s greatest writers must share the blame. Chaucer recounts a blood libel in “The Prioress’s Tale;” Marlowe casts Barabas in The Jew of Malta as a pantomime international financier. Then there is the most famous Jew in literature, Shakespeare’s “dog Jew” Shylock. Marcus points out that Shylock’s “new and fantastic” views on Christians and interest make him the Bard of Avon’s own imagined Jew. The reader is left feeling disconcerted by widespread versions of the imagined Jew, with ancient hatreds still being reinterpreted into modern ones.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply