It’s four years since I gave up opera criticism. The pandemic had struck, I had hit a significant birthday, and notched up three decades at the coal face — a quarter of a century at the Telegraph, and an earlier stint at this address. There were other things I wanted to do and after reviewing something like 2,500 performances, I had said everything I wanted to say, several times over, and knew that it was time for other voices to be heard.

Truth be told, I was becoming a little jaded. My blind spots — opera seria, the final eight mediocrities of Richard Strauss, Rossini’s irritating comedies — were turning cancerous, and I was even tiring of masterpieces like Tosca and Die Zauberflöte: no reflection on them, simply the effect of over-familiarity. “Don’t you miss it?” friends still ask. Absolutely not. I happily fork out for the occasional ticket for “quality assured” performances with fabulous singers, and let everything else go their sweet way. To satisfy any spasm of nostalgia I also have recordings and memories.

Something strange has happened to my taste: I have developed a visceral allergy to Wagner’s music

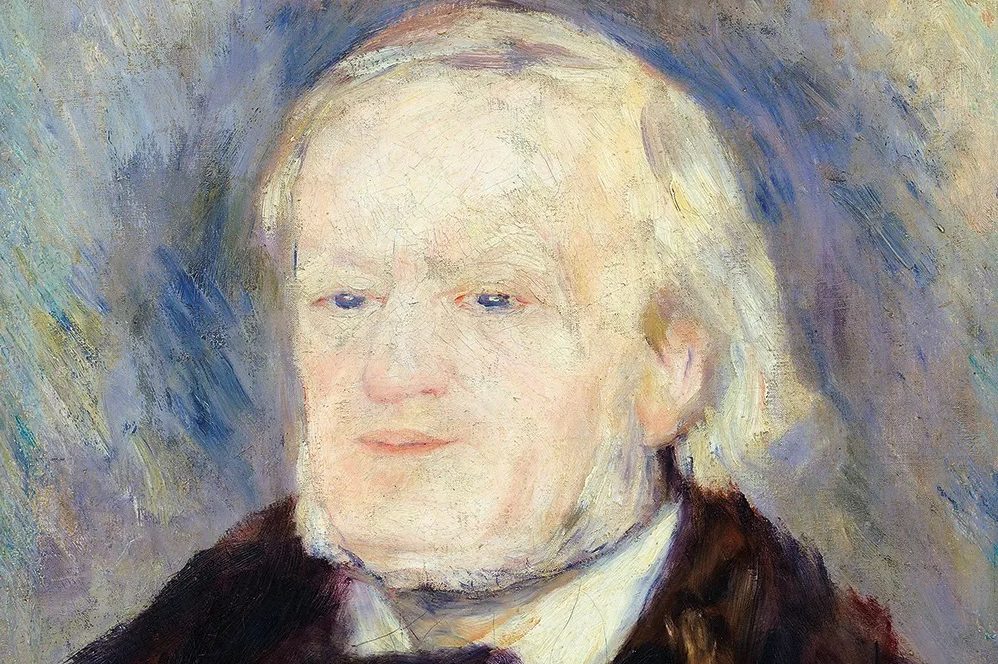

But something very strange has happened to my taste, something I didn’t expect and can’t quite account for: I have developed a violent and visceral allergy to Wagner’s music. I really can’t listen to it at all, and while it’s easy enough to avoid it on stage or in the concert hall, if it catches me by chance on the radio, it induces an almost nauseous repulsion and something weirdly like embarrassment. It is just too much.

This disenchantment shouldn’t happen. Once you have seen the Wagnerian light, it only gets more intensely fascinating, more alluringly elusive — or so we have been told by fine minds such as Michael Tanner and Roger Scruton (note, incidentally, their gender: women don’t feature much in this field). It comes with a lifetime sentence, causing a physical addiction that enters your bloodstream and changes (perhaps poisons?) your view of the world. It is as much religion as art, something you believe in inexhaustibly and indelibly.

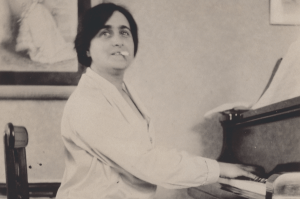

I was one such paid-up Wagnerite. Hearing Reginald Goodall conduct in the 1970s provided the primary infection. Since then I have made several pilgrimages to Bayreuth, sat through at least ten Ring cycles, and trawled the archives to worship the legendary interpretations of Frida Leider and Hans Knappertsbusch. I’ve thrilled to Nina Stemme’s Isolde, Waltraud Meier’s Kundry, Bryn Terfel’s Dutchman. I’ve marveled at Bernard Haitink’s Lohengrin and Christian Thielemann’s Tannhäuser. I’ve raved about Richard Jones’s production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and Stefan Herheim’s Parsifal. And above all there was a Parsifal in Munich in 2018, when a cast led by Stemme, Jonas Kaufmann, Christian Gerhaher and Rene Pape, conducted by Kirill Petrenko, collectively ascended into some transcendentally sublime zone and left me stunned. Perhaps this was the point, perversely, at which the worm turned: I had reached a climax and the gauge could go no higher.

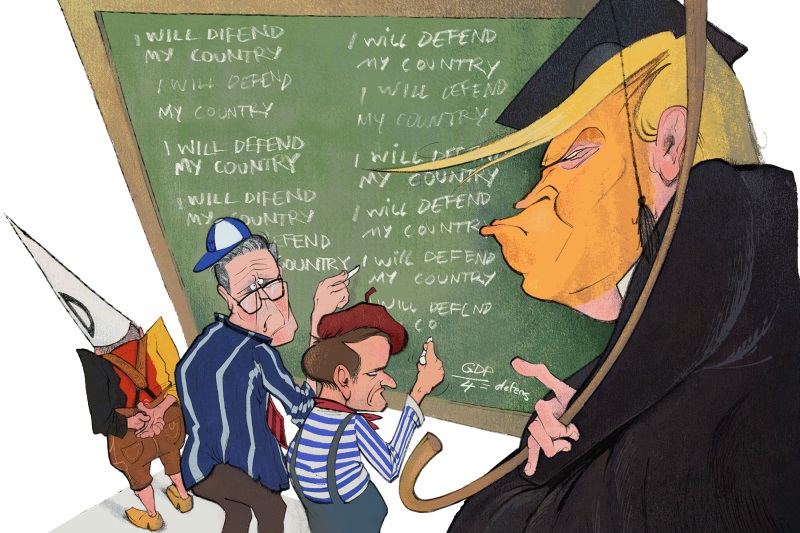

Nietzsche presents the classic example of a Wagnerian apostate: after a long period of infatuation, he decided that Parsifal was “all nerve, no muscle” and turned to the Mediterranean delights of Bizet’s Carmen instead. But complex personal and ideological considerations affected his argument, and my case carries a longer historical perspective and different symptoms. I don’t much mind Wagner’s everyday nastiness. Even his notorious antisemitism — which should be considered alongside his bristling contempt for the British and French — seems to me so crassly stupid that I can only ignore it and, pace commentators such as Barry Millington, I don’t feel it has much bearing on the operas. The real problem is I’m just not convinced that Wagner’s libretti merit the heavyweight intellectual attention they have enjoyed. They work through the common currency of German romanticism and are governed by Wagner’s innate sense of drama rather than metaphysics. In other words I have the temerity to think that they aren’t the philosophically sophisticated tracts that Scruton, in particular, wants them to be.

For me, the Ring is a ripping yarn, a superb feat of storytelling, working best at face value as a theatrical blockbuster (George Bernard Shaw noted how Götterdämmerung followed all the conventions of Meyerbeerian grand opera that Wagner professed to despise) rather than a critique of capitalism or a gloss on Schopenhauer. The second act of Tristan und Isolde offers a remarkably candid representation of the rhythms of intense sexual intercourse, but it communicates to me nothing of any profundity about the realities of human love. Through the allegorical mists of Parsifal, Spenglerian parables of European decadence and premonitions of Nazi racism have been spotted, but on a clear day, would an innocent eye see anything solid except pseudo-Arthurian hooey along Pre-Raphaelite lines?

Wagner is the most demanding and commanding of composers: he is no good at being quiet or — for all the pious talk about “Mitleid” in Parsifal — sympathetic. He doesn’t trade in nuance or irony. His music is immersive, to use a fashionable term, and the trouble with immersion is that it leaves one in danger of being stifled or drowned. There is no room for modesty in the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk (as there is even in Mahler’s giant symphonies), and although Meistersinger does contain flat-footed comedy of sorts, it lacks wit. Perhaps I’ve been corrupted by the restless anxieties of the TikTok era, but I’ve come to resent the stately pace of the Wagnerian chronometer — how did I ever endure the slow-and-grim first act of Lohengrin, I ask myself now — and my impatience has led me to marvel even more at the mercurial ease with which Debussy, deeply indebted to the model of Parsifal though he is, makes melody out of ordinary speech in Pelléas at Mélisande.

Wagner is the most demanding and commanding of composers: he is no good at being quiet or sympathetic

In my current frame of mind, it seems to me that the best of Wagner’s music lies in his depictions of the natural world — the sunny woodland interludes of Siegfried, for instance — where he seems to relax and become more human. Pontificating old men with beards bring out the worst in him: two of his most egregious failures of artistic tact are the finger-wagging Marke in Tristan and the sermonizing Gurnemanz in Parsifal. Let’s be frank about it: they are bum-numbingly boring, and there I sat, listening to their dreary blather, thinking it was my fault and that if I only waited, their wisdom would be revealed. Finally, I got fed up and left.

I suppose this might be just a phase and my former reverence will return: I’ve been through ups and downs with other composers, as I guess we all have. Wagner won’t go out of fashion, of course, and his influence has been so pervasive that it’s become impossible to imagine how western culture would look without him. But that’s part of the problem — he blocks the road, even though plenty of anti-Wagnerians have attempted to blast their way through the barriers.

I’m not anti-Wagnerian — he is indisputably a major genius, even though he’s not engaging little old me at the moment. Yet I realize I’ve been cowed over the years into buying into the view that Wagner’s operas rank as the summit of the art form rather than an episode in its ongoing history embodying one limited set of aesthetic possibilities.

Well, that’s all over. Having long been awed by the grandeur of what Wagner achieved, I’ve become aware of what he didn’t, and I’m having such a nice time with Haydn, Wolf, Poulenc and Ligeti, friendly fellows without any of his ambition to blow your mind or change the world.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply