Barbecue is a fact of life, especially in America. Long summer evenings and reliably good weather make it an easy choice — plus turning on the oven heats up the house to an intolerable level, so if you want a hot meal, outdoors it is. When I was a kid my mom wouldn’t turn on the oven for the entirety of July and August. It was burgers, salads or quick quesadillas on the grill every night of high summer.

Americans have been barbecuing pretty much since before the nation was a nation. The tradition came up from South and Latin America with the invading Spanish. Barbacoa they called it, and they’d use green wood so it cooked long and slow. Americans in the pre-Civil War South had big barbecues for the Fourth of July, just like we do today. Records from shortly after the Revolution detail large outdoor gatherings across the southern states; in 1808 residents of Oconee County, South Carolina “partook of an elegant barbecue” in an “agreeable and natural arbor” to commemorate the Fourth of July. All of America celebrates the Fourth this way, but for the particular flavors and traditions of traditional barbecue, the rest of America can thank the South.

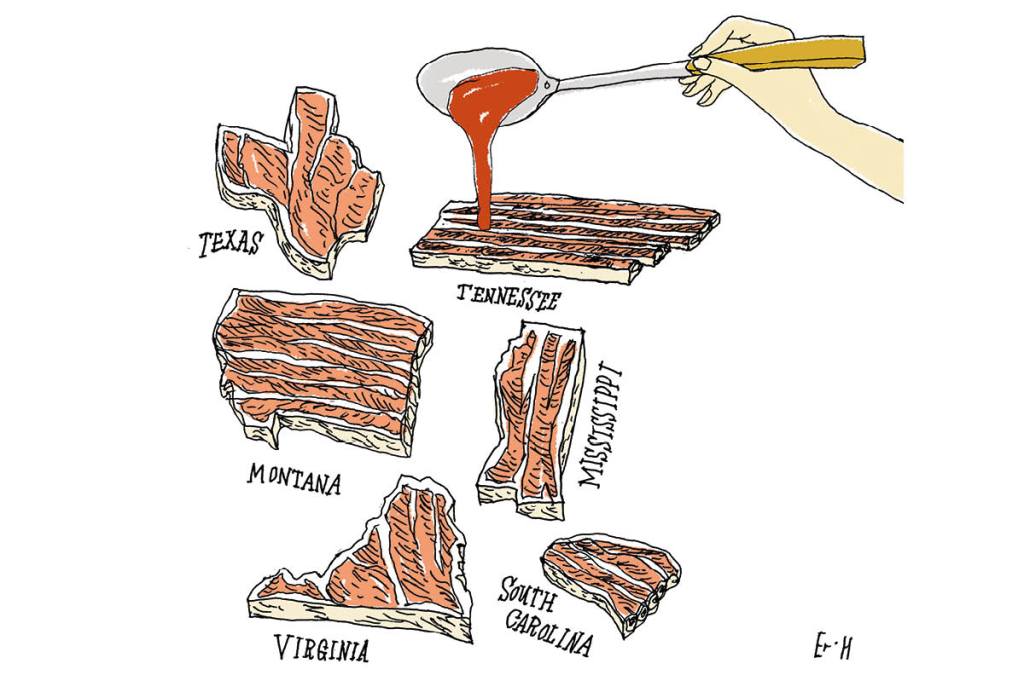

The development of barbecue in the US seems to have been a result of regional necessity, based on the kind of animals the land can support. In the South, barbecue isn’t barbecue if it isn’t pork. Pigs are easier to keep than cows and sheep — they don’t need thousands of acres to sustain them. If you have to, you can even set them loose to wander the woods where they will grow tough and lean. This necessitated the “slow-cook” process — it takes a hell of a long time to tenderize pork if it’s been running loose in the hills. In the South, pork has long been a point of pride. By the nineteenth century, the reputation of good southern pork had spread to the northern states. According to South Carolina barbecue expert Robert F. Moss, as tensions built between the North and South, the southerners refused to sell the northerners their meat. They kept sending their cotton, but not the pork.

The Europeans added sauce to the native barbecue tradition. Surprisingly, it was the British colonists who introduced this culinary revelation — basting meat in juices to keep it moist — although they probably got that idea from the French. In Virginia the British settlers used vinegar and in South Carolina the French and Germans brought their mustard to the table. But the classic sweet and spicy combination of today’s barbecue sauce can be traced back to Memphis, Tennessee, a busy meetingplace of cultures and flavors for the past several centuries. Memphis is ideally located as a river port. Molasses, spices, slaves and cotton came up the Mississippi into Memphis and were sold at the purpose-built market. Perhaps Memphis today can claim a place as one of the great port cities of the world, not unlike its namesake — if you care about barbecue and the blues, that is.

Once settlers started pushing west, they took barbecue with them, though the ingredients evolved with westward expansion. Leave it to Texas to do its own thing — they swapped pork for beef but kept the mustard. To be fair to Texas, you can’t grow much there except cattle so the transition to beef makes sense. The same is true for my home state, Montana. We got our cows from the great Texas cattle drives — Lonesome Dove style — and Montana has been a world-class producer of beef ever since.

In my childhood beef was a regular on the menu. Beef in tacos, beef burgers, beef in roasts, in great sizzling slabs, charcoal-crusted. Montana’s cuisine has also been influenced by the migration of Europeans in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The Poles brought kielbasa, and today my hometown of Great Falls produces the world’s best sausage — the Beer Baron, a smoked kielbasa made from both beef and pork. Long and fat and a rich red color, it’s best charred on the barbecue, emerging with beautiful black grill marks straight onto the bun, and best dressed in ketchup, hot mustard and sweet relish.

Montanans like their meat cooked to a cinder — or maybe that’s just my family. If the meat isn’t coming off in crusted black splinters, it’s not done yet. It’s cooked hot and fast. Huge tendrils of flame leap up from between the grills of the pot-bellied black kettle barbecue. Feed the flames with more gasoline — it’s not hot enough. In Montana, firing up the barbecue is a way to keep the bugs away; cooking on it is an added perk.

Whoever thinks America’s great addition to world cuisine is fast food clearly hasn’t had a steak straight off the open-flame grill. You can get the same burger from a McDonald’s almost anywhere in the world these days, but you can only get a Beer Baron grilled on an open fire in Montana.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2023 World edition.