I know straight away, from the look on my friend Alice’s face, whether it’s a “bad caretaker” day. Five years ago Alice had a fall and she can’t now do stairs, so she lives just on the second floor of her maisonette in north London. When I drop round, the carer is usually in the kitchen and Alice in her bedroom/sitting room next door. If it’s a bad carer day, she’ll look towards the kitchen, do a thumbs-down sign, purse her lips and shake her head, then she’ll wriggle her shoulders — hoity toity — to indicate that she feels bossed about.

Alice is entirely dependent on the care company the council employs and appeasement is all she has

I suppose infirm eighty-eight-year-olds often need to be bossed about in a way. There are hundreds of thousands of people, taken care of at home like Alice, and they need to be dressed, fed, heaved on and off the portable potty chair. But Alice isn’t making up the bad carer days. She’s a beady old woman who doesn’t complain lightly, and if she’s nervous of a caretaker, it means she has reason to be. On “bad caretaker” days her hair is unbrushed and knotted and when she asks for tea, she’s told no, so as to minimize potty trips. She’s often had cheese sandwiches for both lunch and dinner, I notice and she stays all day in her nightie. I had thought a reluctant caretaker might be particularly grateful for visitors, but it’s the surly ones who want me out quickest and glare until I leave.

I find it fascinating and alarming that without ever having planned it as a strategy, on a bad caretaker day, Alice and I will both talk as loudly as we can about how fabulous the caretakers are and how lucky she is to have them, in the hope they’re listening. We have never discussed doing this because we can’t. Alice is stone deaf and we interact via mime and amiable miscommunication. For years, for instance, she’s been enquiring kindly about my progress on the piano as a result of my attempts to mime typing. But even when you’re eighty-eight and often confused about which century we’re in, the survival instinct is keen. Alice knows full well she is in a hostage situation. She’s entirely dependent on the care company the council employs and appeasement is all she has. I remember behaving the same way around a hostile live-in nanny.

I visit because I like Alice and because it’s easy. She lives just round the corner. But I’ve also found myself taking mental notes for my own old age and for all the future old. I remember my now influential friend James Forsyth, once the political editor at The Spectator, talking optimistically about a return to the days when families tucked their octogenarians into spare rooms or attics, or annexes if they were country folk and flush. I seem to remember that he thought this way of living might somehow return if the incentives were only right. It seems implausible.

Alice lives in the past, mostly the 1980s, but she’s a picture of the future too. Her children don’t help to care for her, in part because they don’t live anywhere near. They can’t afford to live in the part of London where they grew up, and besides they’re pensioners themselves. Alice’s daughter lives several hundred miles away with no car and bad legs and Alice’s favorite, her handsome, feckless son, seems to finds that the less he sees her, the less his conscience is troubled. When you’re not living anywhere near your own lonely old and when like Alice they’re unable to call or talk on the phone, it’s easy to persuade yourself that they’re best left undisturbed. I shall wait till my son settles, then buy a ground-floor flat round the corner from him and halloo as he passes on his way to work. It’s only recently occurred to me, I’m afraid, the burden I might have placed on him by not having more children. This too is the future. The ranks of the elderly are growing. Fewer children are being born. The great gray bulge is coming, with ever fewer young people to support them.

By her own admission, Alice loved her daughter less than she did the feckless son. Do you have a duty to care for a mother who didn’t care for you? Perhaps those of us still bobbing about in the wake turbulence of the established church might at least recognize the obligation to honor our parents. But will a generation of children taught to despise past generations really put themselves out for their demented, cantankerous elderly people? They’ve been told that their first duty is to their own mental health and… it’s “a lot,” as they say. When Alice has had a bad night and she’s disorientated, she sometimes has a rant about immigration and how London has changed. There’s not much to be done about this. The elderly brain loses the ability to inhibit and we’re all shot through with fear and spite. Will a generation steeped in progressive ethics understand when their oldies go on like this? Will the caretakers?

Alice is one of the very luckiest eightysomethings. She lives in her own house and has avoided the living hell of most council-run care homes and geriatric wards so far. She has no chronic pain. It struck me the last time I visited that this is as good as it gets. Alice is living the dream. It’s a worrying thought.

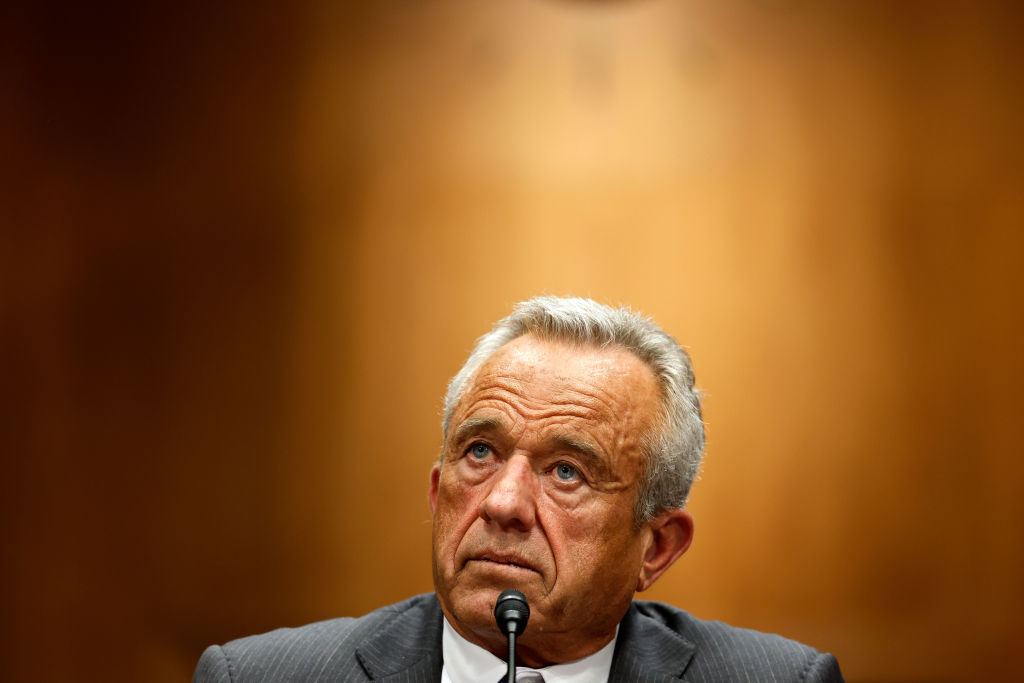

But there is a bright side, which is Kay. Kay is in her early twenties and she’s from Nigeria, and she arrived in 2023 when caretakers were suddenly allowed in under the skilled worker scheme. For the last year Kay has been Alice’s semi-regular caretaker and she’s a godsend. When Kay has been round, Alice’s hair is brushed and gleaming and put up in a series of eccentric accessories; she has tea and she smiles. “Kay gives me a kiss,” she tells me, delighted.

Alice’s life has value when Kay’s been around — it’s important that anyone too ardent about euthanasia understands this. Kay says it’s important to honor the old and that she treats Alice the same way she would treat her own grandmother. If there were more caretakers like Kay, it would all be almost bearable.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply