Were Pulitzer Prize-winning “author” John F. Kennedy — I mean Ted Sorensen — to write Profiles in Courage today, taking his subjects from the contemporary political world, his pickings would be mighty slim. I suppose he might produce one of those comically brief novelty books, à la Steve Miller’s Higher Poetics or Hot Stuff by Mamie Eisenhower.

For my part, I can’t think of a sharper modern political profile in courage than that cut by Tennessee Republican John J.“Jimmy” Duncan, Jr., who represented Knoxville in the US House of Representatives for thirty years before his retirement in 2019.

Jimmy — full disclosure: I am a friend and admirer — was one of the six brave and prescient House Republicans who resisted intense lobbying by George W. Bush and his lying courtiers and the braying of jingoes to vote against the US invasion of Iraq in October 2002.

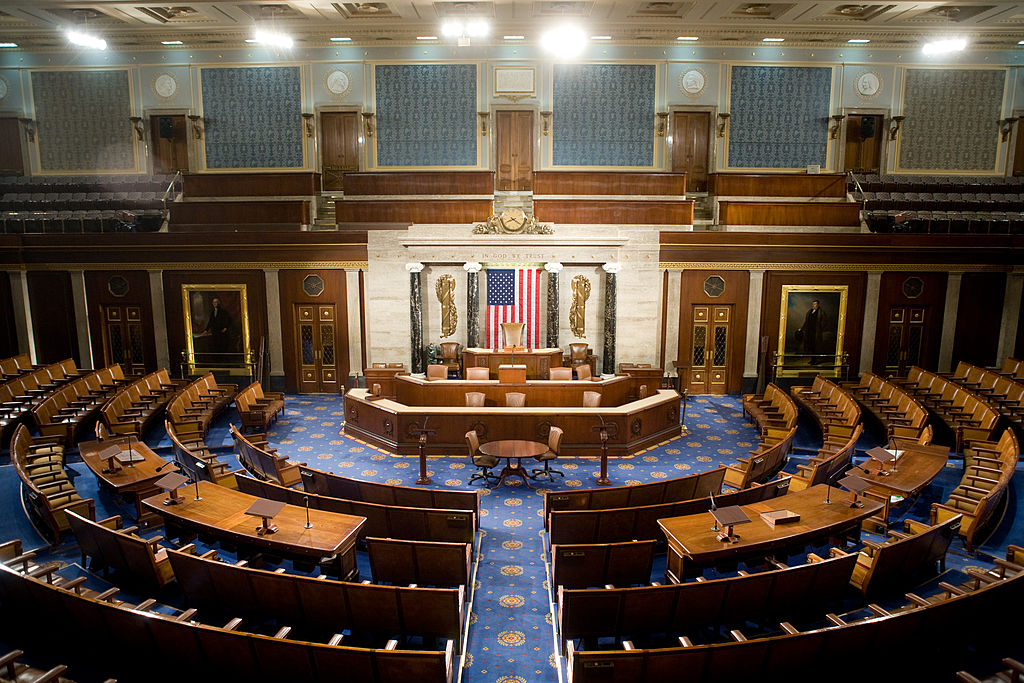

Given that the architects of this catastrophe paid no price whatsoever — that will have to wait for the afterlife — and the Republican politicians who gutlessly caved to Bush went right on being reelected, and the talking heads who squealed with delight over the rockets’ red glare experienced none of the discomforts of life during wartime, the least we can do for that noble sextet is to say their names: Jimmy Duncan, John Hostettler, Amory Houghton, Jim Leach, Connie Morella, Ron Paul.

Like Fighting Bob La Follette dissenting from that sanctimonious prig Woodrow Wilson’s “War to End All Wars,” they risked obloquy and worse for advancing two propositions. 1: The United States should not be the world’s policeman, and 2: Thou shalt not kill.

You might think Proposition Two would find favor among Decalogue devotees, but a church in Lenoir City, Tennessee, revoked Duncan’s invitation to deliver a lay sermon when its biggest contributor threatened to quit and take his pieces of silver with him if this peacenik in Republican clothing were permitted to profane the pulpit.

Jimmy Duncan has just published a charming memoir, From Batboy to Congressman, which is brought out, fittingly, by his hometown University of Tennessee Press. The book, organized as a series of vignettes, stories and character sketches, wonderfully demonstrates why this thoughtful and self-effacing man cruised to victory every biennium — even after he’d been sternly warned that his anti-Iraq War vote was a political suicide note.

Jimmy Duncan is a man who knows his place, which is one of the highest compliments I can give. That place is Knoxville in East Tennessee, the traditional Republican outpost of the Upper South, for which he has a fully requited love.

His father and congressional predecessor, John J. Duncan, Sr., served as the city’s mayor and was co-owner of the local minor league baseball team, the Knoxville Smokies. No childhood job is more desirable than that of batboy, a position young Jimmy filled for the Smokies for five and a half years. (He was picking up the lumber the night the legendarily bibulous smoke-thrower Steve Dalkowski struck out twenty-one and walked twenty-two.)

Fred Rooney, a former Democratic congressman from Pennsylvania, once told Jimmy, “Your dad was the only man I ever knew who never had an enemy in this town.” The son was similarly without foes. “I felt that I had to get along with those on the opposite side if I wanted to get things done for my constituents,” he writes. “Besides, it was just more pleasant to try to be kind to everyone.”

Mavericks can be prickly sorts, congenital argufiers and contumacious contrarians. Jimmy Duncan, while compiling a principled and party-line-defying voting record of fiscal parsimony, social conservatism, America First patriotism and powerful skepticism of the military-industrial complex, seems to have won friends on both sides of the aisle and in shunpikes far from any known aisle. His book includes affectionate recollections of Democrats Tip O’Neill, Bill Clinton and Bernie Sanders, as well as homefolks such as Archie Campbell (a cast member and the head writer of Hee-Haw who composed “Pffft! You Were Gone”) and a mélange of elderly dames named Hazel.

It’s nice to be important, but it’s more important to be nice. This would draw contemptuous snorts from purposeful striders down the corridors of power, but Jimmy Duncan practiced it every day. He was the kind of guy who chatted easily with the folks who served food in the House cafeteria. He genuinely likes people.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2021 World edition.