The internet has been good for cats. “Cute cat videos” dominated early YouTube and continue to be default Instagram Reels and YouTube Short recommendations. Some influencer cats — like Grumpy Cat and Karl Lagerfeld’s heir Choupette — hog the headlines, control tens of millions of dollars in social media and advertising contracts and out-earn many famous human influencers. There are cats significantly richer than you, whose selfies pay their owner’s mortgage. Taylor Swift’s cat Olivia Benson has a net worth of $97 million, which makes her only the third wealthiest pet in the world.

It seems odd. But then again, cats have worked for and been worshipped by humans for thousands of years, be they the feline goddesses Bastet, Sekhmet and Mafdet, or your humble farm cat, destroying rats, mice and gophers in exchange for goodies and rubs behind their ears and under their chins. One genetic assessment of close to a thousand domestic cats and their wild progenitors indicate that cats were first domesticated in the Near East, most likely in an agricultural development in the Fertile Crescent. Another DNA analysis indicates that populations of Felis silvestris lybica in the Near East (during the Neolithic period about 9,000 years ago) and Egypt (during the Classical period, around 12,000 years ago) contributed to the gene pool of the modern housecat at different times.

And to this day, away from viral TikToks and influencer contracts, there are many hard-working, normal cats who keep the economy going. For many vintners, cats have become their favorite unsung but essential partners in pest control and free PR.

A lovely midnight-black cat, Pete was long past his hunting days.

“By the end of his life, he was deaf, blind and arthritic and had not caught a mouse for a few years,” says Allyson Bycraft, associate winemaker at Babcock Winery & Vineyards in Lompoc, California. But his being there was enough. Placing domestic predators in farms and rural homesteads creates a “landscape of fear,” where rodents know not to snack on juicy grapes, even if the predator is not capable of catching them.

“Just his presence and smell was enough to keep the varmints at bay,” Bycraft says. But within a month of his death in 2016, at twenty years old, “We were overrun by mice.”

Brian O’Donnell — proprietor and winemaker at Belle Pente Vineyards in Carlton, Oregon — had the same experience. “When we found ourselves ‘cat-less’ several years ago, we noticed a dramatic increase in mouse activity in our office and winery, [but] we got some cats again, and the populations in and around the office, barns and winery returned to essentially zero.”

Belle Pente currently deploys two teams of two: Mork and Mindy handle the action around the winery; Cougar and Chippie combat vineyard pests. Though they only stray 250 meters or so from home base, a kitty outpost further afield would put them at risk from other predators, like coyotes.

Winegrowers face a seemingly endless list of foes. Mice, gophers, voles and moles can reproduce prolifically on a diet of vines and cover crops and cause havoc for a working vineyard, just as bats and snakes can in storage facilities, and all of them make other issues worse, from fungi on partly eaten produce to insect infestations. Alongside unexpected climatic events, heading to work amid the vines often entails suiting up for at least one Biblical plague. But cats help avoid less appealing alternatives.

“Using cats means we don’t have to use poisons or other methods to protect our vines and our winery,” says Kathleen Inman, owner and winemaker at Sonoma’s Inman Family Wines. Along with greeting guests and cheering staff, Inman says the three cats they’ve had over the years have become an essential component of their “integrated pest control.” Inman’s current head kitty, Vini — a watchful gray and white, green-eyed hunter — destroys gophers and snakes in the vines and mice around the cellar.

In turn, just as cats help the winemakers, vineyards can be perfect homes for cats who wouldn’t be happy in a studio apartment. Feral cats, for instance, are not fully domestic, don’t bond with humans as easily and are often too aggressive to live indoors. Homing them at all involves a month of semi-confinement until they bond with at least one person there, and with the place itself. But once they settle in, they can make perfect partners for a vineyard. This was the case for a five-month-old pair of black cats, who made their home at Babcock after the vineyard worked with the Santa Barbara nonprofit Catalyst for Cats (dedicated to helping feral cats find safe spaces). Felix checks the tasting room when Bycraft opens, and Reggie follows her to the warehouse, “clearing out any troublemakers.” Bycraft hasn’t had a mice problem since.

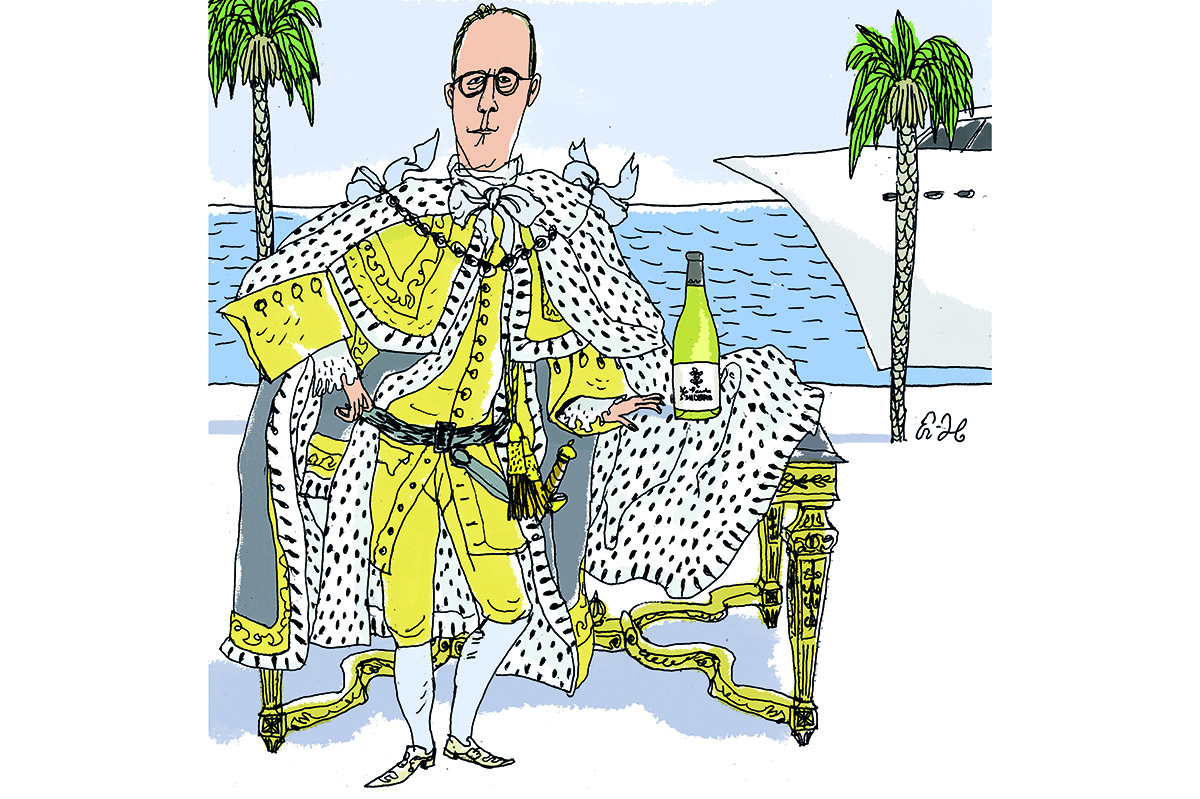

“One thing I’ve learned working with so many animals is that each animal is an individual,” says William Allen, who cofounded Two Shepherds Wine in Windsor, California with his life and business partner Karen Daenen. They had bought what he characterizes as a “dilapidated” farm teeming with mice and rats in 2008 and have spent the years since mending all the farm buildings, planting a small vineyard and transforming the infrastructure. Without cats, they say, it wouldn’t have been feasible. Allen’s appreciation for the cats is such that he has named lines of wine for them and featured their likenesses on bottles.

Like the team at Babcock, Allen and Daenen got all three of their cats as kittens, though only two actually earn their keep by hunting. Wiley, their “ten-pound panther,” regularly kills ferocious wild rabbits and as a kitten would bring live rodents to the house, then “went through a stage of bring- ing us gopher heads from the vineyard.” He only comes inside when the weather is particularly inhospitable. By contrast, Carignan is more a hybrid inside-outside cat, “a good hunter, but Carignan also likes to chill with us,” Allen says. “Now Max, on the other hand, is a complete lover, and definitely not a hunter.”

Though they don’t rake in the millions of professional influencer pets, vineyard cats are beloved among vineyard visitors, but it’s sometimes strikingly obvious that they aren’t fully domesticated. Benny — a large, long-haired, yellow-eyed black beauty, and current CMO (chief mouse officer) at Gary Farrell Vineyards & Winery in the Russian River Valley — is very social with guests, but his show-and-tell can be somewhat confrontational.

“He is a voracious hunter, and he is not shy about it,” notes Theresa Heredia, winemaker at Gary Farrell. “Once, he killed a vole and brought it out in front of our customer-seating area and happily crunched through the bones in front of them. But at the same time, he is such a sweet cat. He’ll come running across vineyards and fields when I call him and bound into my arms like a long-lost lover.”

“One night about five years ago, we had a dinner and we were outside saying goodnight, and there was this little cat running around and coming up and loving on us,” recalls Maeve Pesquera, senior vice president of Daou Vineyards in Paso Robles.

“It’s very unusual to see cats up here” — their tasting room is 2,200 feet above sea level, with coyotes, wild boar, mountain lions, bears and foxes skulking about — “but she stuck around. We found out she was staying safe at night by sneaking into our belltower, which is why we named her Bell.”

“We were all completely in love with her, and posting photos of her on social media,” Pesquera explains, pointing to Bell’s Instagram account, which recounts some of her more palatable adventures.

“And then our neighbor called and said he wanted our cat back. Everyone was sobbing. George [Daou, the co-proprietor] happened to be there and he was so confused. He was like, ‘What can I do? I’ll buy you another cat. I’ll buy you two cats!’ But we wanted Bell.”

To keep the peace, they returned Bell to their neighbor, whom they were on good terms with. But Bell wasn’t having it — she kept on escaping and returning to the vine- yard — despite almost losing her life to a hungry hawk.

“A hawk just swooped over and picked Bell up by the neck,” Pesquera recalls. “Everyone in the tasting room came running out, screaming. We must have spooked the hawk because it dropped Bell after like twelve feet. But she just shook herself off and looked at us, like, ‘Who cares? Relax, people.’”

Now, Pesquera explains, they have an excellent co-parenting relationship with their neighbor. And Bell more than earns her keep.

“By night, she is a fierce huntress,” Pesquera says. “By day she is a princess queen who loves to be adored and petted. Visitors come into our tasting room and take pictures with her and feed her prosciutto.”

Unlike other domesticated animals, when cats decided to co-exist with humans, they didn’t change their inherent spirit or personality. They know they’re lions. But they also know they deserve every last scrap of that prosciutto, so keep it coming.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply