Most readers will come to this column in February. “That’s the dead of winter,” you say (if you are in the Northern hemisphere, anyway). But I write at the absolute nadir of daylight.

For some years now, I have kept a daylight diary. I generally start in mid-October and go through the return of daylight-saving time in March. It takes that long to convince me that summer really is on its way back. When I started, I simply noted the time the sun rose, when it set and how much daylight we had that day. I eventually got a little more elaborate, noting the phases of the moon and such, and making very brief annotations about significant events. Every year (so far), it’s been a story with a happy ending. As I write, there are but nine hours and thirteen minutes of daylight in Connecticut. But let’s say you are joining me for a glass of wine on February 1. That day, there will be about ten hours and five minutes of daylight. Who says there is no such thing as progress?

I know what you’re thinking. “This has nothing to do with wine, your announced topic.” Sed contra, as St. Thomas was in the habit of objecting. Everything has something to do with wine. I just mentioned sharing a glass of the old fructum vitis, did I not? And, naturally, my purpose in nattering on about moving from the tenebrous slough of winter solstice to the frigid but (relatively) more illumined hours of February was to introduce a couple of objective correlatives of that hope-inspiring process.

First, as a sort of praeludium, let me mention an excellent Champagne whose acquaintance I recently made: the 2012 Clos des Monnaies from the storied house of Goutorbe-Bouillot in the Marne valley. The wine, equal parts Meunier and Chardonnay, comes from a diminutive clos of about three-quarters of an acre.

Regular readers will recall my recent column about Sherry. I mention there the solera system through which several vintages are blended to produce each year’s wine. Goutorbe-Bouillot deploys a similar technique, using 50 percent of past vintages in its annual amalgam. As one critic noted, “This intricate dance results in a wine that bears the imprints of bygone vintages, each contributing to a symphony of flavors and textures.” In the case of the 2012 Clos des Monnaies the result is rich, toasty-lemon effervescence, elegant, articulated, sumptuous. You should be able to find a bottle for about $120.

Second — and this brings me to the real motivation behind that contracting-darkness-gives-way-to-Spring motif with which I began — a friend recently shared a remarkable piece of correspondence from the great Burgundian winemaker and négociant Joseph Drouhin. Written in 1944 from recently liberated France, it is a response to a letter from my friend’s grandfather, who had been on a wine trip in France with his son in the late 1930s. They had ordered from Drouhin three cases each of the 1937 Romanée-Conti and Richebourg (I’d tell you how much that would cost today, but I cannot count that high).

They never got the wine because of the war. Moreover, Drouhin noted, the “Boches” had demanded that the French declare whatever property of American citizens they might hold. Drouhin declined to tell the Germans about the wine, which he had kept safe in his cellar. “Je suis heureux,” he wrote, “d’avoir pu vous les sauver.” The part of the story I do not know is whether they ever got the wine. I hope so.

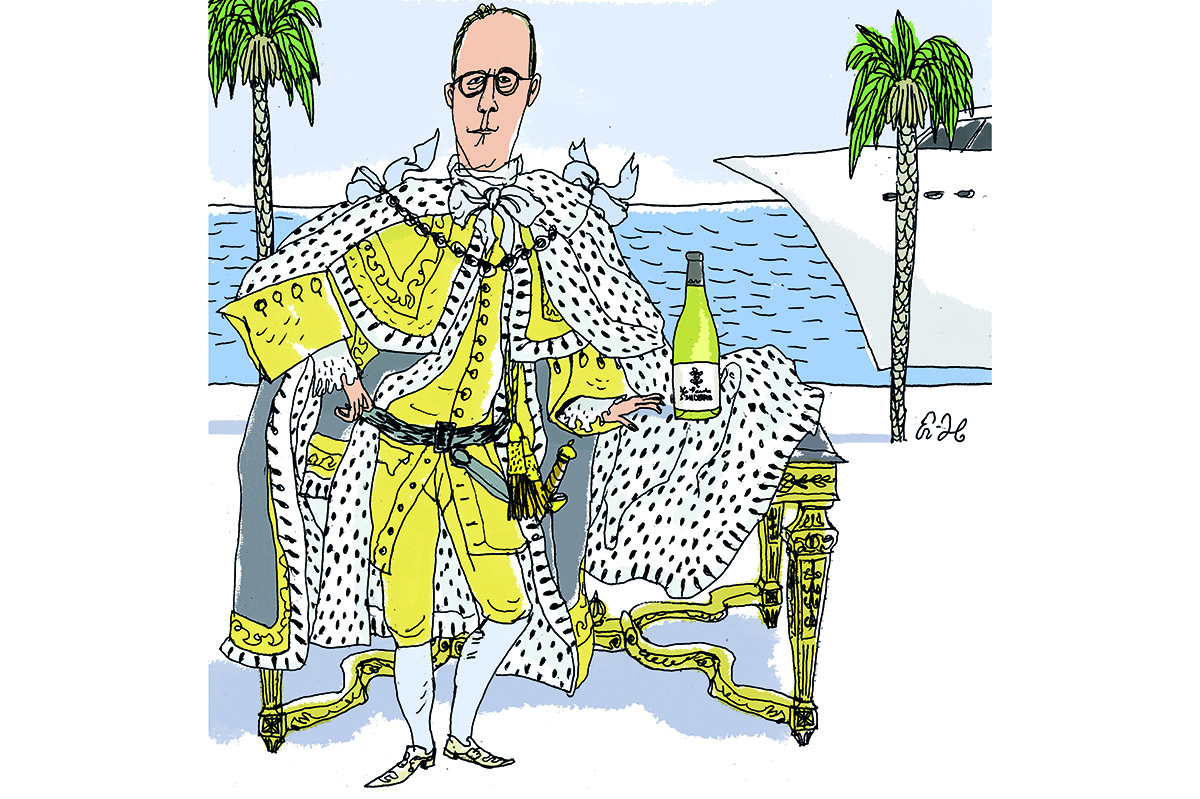

I will always think of that letter when I drink a wine from Joseph Drouhin, which is often. The venerable, still family-owned business dates back to 1880, when 22-year-old Joseph moved from Chablis to Beaune to start the business. The company has scores of properties throughout Burgundy and, as of 1988, in Willamette Valley, Oregon. The wines range from pleasantly potable to excellent to spectacular. I see from my dinner diary that they are frequent guests at Thanksgiving, Christmas and other festive occasions. One recent Thanksgiving featured a Drouhin Gevrey-Chambertin and Chassagne-Montrachet, both from 2014 and both $100. For some reason, we also had a 2014 Puligny-Montrachet from Drouhin that year — research no doubt — which we got for about $75.

The letter reveals an almost heroic character, and a grateful one, too. Drouhin notes in passing that he had been imprisoned for seven months and had happily, just before the liberation, escaped a second arrest, qui m’aurait été certainement fatale. He is also profuse with his thanks for America’s aid in ejecting “the Boche.” “Je tiens à vous dire toute la reconnaissance des Français pour ce que la grande nation américaine fait de nouveau pour venir à son secours — Nous ne l’oublierons jamais.”

I am not sure later generations share those sentiments. But it is edifying in this moment of darkness to believe that they might.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply