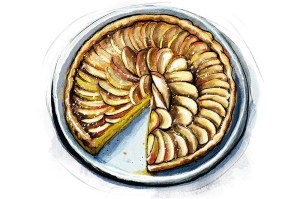

What do the works of Le Corbusier, driftwood on the beach and French cherry tart have in common? Well, all three are improved by being set on fire. That’s uncontroversial when it comes to two items on the list, but perhaps you’re inclined to quibble about the tart. Resist the temptation, messieurs-dames, for I have an irrefutable authority up my sleeve: Julia Child, the lady whose Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1961) was hailed by legendary restaurateur George Lang of Café des Artistes fame as the volume that ‘not only clarified what real French food is, but simply taught us to cook’.

Experimentation with Julia’s recipe for cherry tart flambée definitively proves that the only way to improve on your common cherry tart is to douse it in warm cognac and touch a match to it. And poof: what was once a quietly elegant dessert arrives at the table in a blue blaze of glory, the cynosure of all eyes, while the cook permits herself a restrained yet confident smile. Without disdaining the praise heaped upon her, she mustn’t give the game away by excessive modesty. For as anyone who’s flambéed knows, it’s as easy as falling off a log. The tricky part’s the tart.

I discovered the recipe as I flipped through Mastering the Art of French Cooking in search of cherry clafoutis. The clafoutis of my youth, I am persuaded, was a sort of cherry-studded coffee cake. But on searching for enlightenment via the internet, many hits seemed to locate the word ‘clafoutis’ in uncomfortably close proximity to the words ‘dense’ and ‘custard’.

You’ll understand my discomfort when I explain that not long ago I had a less-than-pleasant experience with a baked food in which dried fruit served as an aggregate in something its friends would have called custard and its enemies freshly poured concrete. Say it isn’t so, I begged Julia, hauling her 1961 classic off the shelf in desperation.

Unfortunately, she offered but cold comfort, for the clafoutis recipe was subtitled ‘Cherry Flan’ — distinctly custardy. (Forgive me, you connoisseurs who know your crème anglaise from your blancmange blindfolded; I know it’s not that simple, but I’ve been scarred.) Anyways, it didn’t matter in the end, because in seeking clafoutis I came across cherry tart flambée and knew my destiny.

The recipe looked easy. Naturally, I didn’t read it all the way through; only unadventurous, play-it-safe types do that. The first decision to be made was whether to use canned or fresh cherries, the author alleging either kind to be suitable. After trying both, I found canned sour cherries were best, lending depth and balance to the otherwise sweet flavor.

I also discovered that using canned, pre-pitted cherries saves you from having to remove the pits from a pint and a half of cherries using the metal icing tip from a cake-decorating kit, an improvised method which works surprisingly well but is somewhat time-consuming and leaves your hands looking a bit like Lady Macbeth’s. Then the cherries soak for half an hour in sugared kirsch or cognac. I used Napoleon brandy, with good results.

The tart shell was next, and if you thought Julia was going to authorize us to use a mass-produced frozen pie shell, think again. Nothing less than home-made pâte brisée would do for her, so I obediently shuffled off to some rather opaque instructions on page 633 which referred me to other instructions on page 17 about measuring flour and then some other ones on pages 140-145 about blending and forming the shell. There a useful sketch guided me in smearing small chunks of dough in six-inch streaks on the countertop, using the heel of my palm and feeling a bit self-conscious. The fine print advised me this was a solemn and important ritual known as fraisage. (The resultant texture was indeed ideal.)

A minor contretemps occurred next. The pastry was supposed to be refrigerated for two hours. I didn’t have two hours, and I considered it rather unsporting of Julia to conceal this information in pages 140-145, no fewer than two redirects away from the original recipe. On the bright side, this undeniable deviousness proved the authentically Gallic nature of the recipe, and I decided to simply pop the dough into the freezer for a while instead. It worked beautifully. Out came the pastry, 30 minutes later, good as gold, submitting with only minor protest to being rolled out and baked.

How charmingly ancien régime it feels to simmer cherries in red Bordeaux wine, a bit of freshly squeezed lemon juice and some sugar! At this stage it seemed only right to pour the cook a glass of wine too. One for the cherries, one for me. The first time I made it, I used a peppery little Cabernet, an Australian Yellow Tail, instead of the Bordeaux, which brought out the fruit flavors admirably. When I tested it with real Bordeaux, I thought it didn’t work as well, but then I didn’t buy the most expensive Bordeaux on the shelf.

If you’ve been soaking the cherries in cognac, they have to be drained before you add them to the boiling wine mixture and let them simmer for a few minutes. Then the cherries have to cool completely in the liquid. I was glad of the drink by the time I got to the next step, for, sure enough, in flew another curveball from Julia. This time she was casually calling for one and a half cups of cold crème pâtissière, which of course every well-prepared chef has tucked away in a corner of the refrigerator. Or, should you by misadventure happen to have just run out of crème pâtissière, frangipane will do.

***

A print and digital subscription to The Spectator is just $7.99 a month

***

Ah, right, frangipane. On examination of my pantry, it became apparent that, through some strange oversight, inventory on both crème pâtissière and frangipane was at zero. Absent a suitable battery of sous-chefs to whip up these household staples, it fell to me to remedy the situation. Julia’s frangipane required quantities of crushed macaroons or powdered almonds, and those were in short supply, so crème pâtissière it was.

Over to page 590 I went, wire whisk in hand. Many egg yolks, much boiling milk, more flour than you’d expect, and quite a bit of elbow grease later — hello everyone, meet crème pâtissière. It wasn’t cold, but with apologies to Julia, it was as close as we were going to get on my schedule. The final step was surprisingly anticlimactic: drain the cherries, fold them into the crème pâtissière with a bit more cognac (no temperance movement dish, this) and fill the tart shell. And voilà.

As St Lawrence, martyred by fire, is the patron saint of chefs — something to do with his merry repartee on the gridiron — how appropriate it would be to mark his August 10 feast with a fiery cherry dessert! Born on the loveliest of trees, the cherry is surely the joyfullest of fruits; and Lawrence’s joy was unparalleled. He would not have liked Le Corbusier. Before serving, sprinkle sugar over it and caramelize under your broiler. Pour a little warmed cognac over the tart and light it up. Enjoy in the dark, as the meteoric Tears of St Lawrence crisscross the August sky.

This article is in The Spectator’s August 2020 US edition.