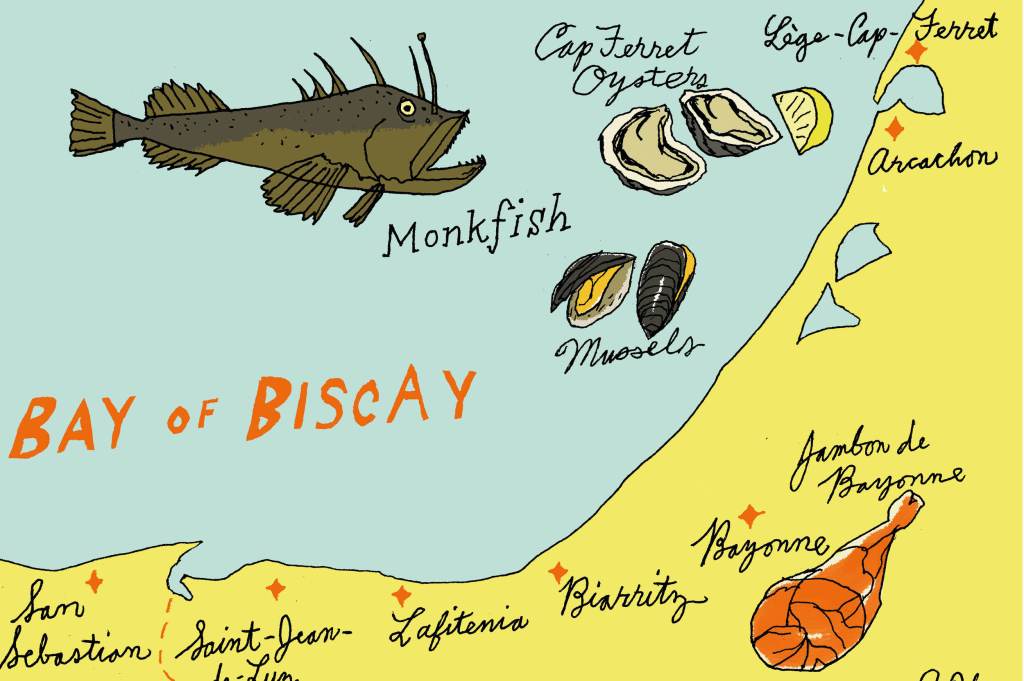

If I’d known what a whole monkfish looks like, I would never have ordered it. It was only weeks later that I saw a picture of the horrid creature: small, wicked eyes, prehistoric head, skin like rusty medieval armor and a gaping mouth overflowing with jagged teeth. Truly the stuff of nightmares.

We’d popped over the border from France into San Sebastián, Spain, for a bite of dinner, selecting a spot a stone’s throw from the Baroque exuberance of Santa Maria del Coro. The daily special was monkfish, and for some reason — perhaps an excess of sun that day — the image that came to mind was, inaccurately, that of the innocent red mullet. The daily special in a fishing town is bound to be fresh, so it seemed fair to give it a try.

The monkfish arrived at the table in fillet form with only one suspiciously shaped bone, meek as its cowled namesake, giving no hint of a misspent youth as terror of the seas. Tenderly bathed in lemon and olive oil, it was delicious, sweet and nutty, justifying its moniker of “poor man’s lobster.”

I am very glad I had that experience, for now that I have seen the true face of the monkfish, I will certainly never order it again. The memory of that one, delightful fillet will remain forever unspoiled.

Climb into your convertible in San Sebastián and follow the coastline north into France, keeping the rocky outcroppings, turquoise waters and small curved beaches of the Côte Basque to your left. In half an hour you’ll come upon the Viper’s Nest, as English sailors used to call the fishing town of Saint-Jean-de-Luz. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Saint-Jean-de-Luz waxed fat and rich thanks both to its whaling trade and its Basque corsairs, who made a handsome living through seizing unwary English ships (in other words, piracy). Today its chief interests are tuna fisheries and upper-crust vacationers: little has changed.

Just outside of town is the stony beach of Lafitenia, where the transparent water glows blue and gold, and surfers ride the waves beyond the point. They serve an excellent hamburger nearby — not exactly the dish for which one travels to France, admittedly, but there are times when a hamburger fits the bill materially, philosophically and spiritually. This burger was enormous, served quite rare in the French style, on a brioche bun. It had everything you can imagine on it, down to a fried egg and a seasoning of coarse sand. At that time and in that place, nothing could have tasted better.

Next stop, Biarritz, “the queen of beaches, and the beach of kings.” Palm trees wave their feathery arms, impossibly scenic chunks of rock dot the waterfront; tourists huff and puff their way up the steep slope from the waterfront into town.

It was here that the crowned heads of Europe took their vacations in the nineteenth century. Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III, took such a fancy to the locale that she had a palace built right on the beach. Today, her villa has been turned into the swanky Hôtel du Palais, where Emmanuel Macron hosted the G7 summit in 2019.

You can park and take the walkway that juts over the sea to the emblem of Biarritz, the spectacular Rocher de la Vierge. It is a wave-battered rock that looks like the hull of a ship, at the top of which stands a statue of the Blessed Virgin. One dark night in 1864, a crew of Biarritz whalers was caught near the shore in a terrible storm. Fearing for their lives, they prayed to the Blessed Virgin for help. A mysterious light appeared above the water, enabling them to steer between the rocks into the safety of the harbor. The statue was placed upon the rock in 1865 as a sign of thanksgiving. Napoleon III, who took a great interest in Biarritz for his wife’s sake, had the first walkway, just over 240 feet long, built out from the mainland over the sea to the rock.

On the road again, heading north; time to put the top back up on the convertible, for this is a major highway now. You pass Bayonne, the home of the ham: jambon de Bayonne is a much-loved cured ham that is not too salty, with a delicate flavor and a somewhat chewy texture. The rules guiding its production are terribly strict, as is the case with every traditional foodstuff in France.

The rocky shoreline of the Côte Basque is left behind. We’re now rolling up the magnificent Côte d’Argent, 150 miles of continuous beach, interrupted only by the occasional waterway. Beloved by surfers for the steady rollers crashing in from the open Atlantic, and by bathers for its fine, endless sands, this section of the coast was dubbed the Silver Coast by poet Maurice Martin for its “foam flashing like precious metal.”

Eventually we’ll hit Arcachon Bay, southwest of Bordeaux, where everyone must stop to try the shellfish. Cap-Ferret is the destination for oyster lovers. Fishing villages made up of tiny, colorful homes are squeezed along the shore next to the oyster banks, and children on holiday attempt to sell seashells for the outrageous price of one euro each.

The cabanes à huîtres are tasting huts run by the oyster farmers. There you can enjoy a selection of French oysters, sometimes only a few minutes out of the ocean, with a glass of local white wine such as Entre-Deux-Mers. Don’t expect seafood sauce or Tabasco; you’re expected to appreciate the oyster itself, with nothing more than a squeeze of lemon and the briny flavor of seawater. Though we found them cheap on the lemon and generous on the brine, the oysters, particularly those from the bay itself, were delightful.

The French love their oysters, and those from Arcachon are considered among the best produced nationally. They are not available in supermarkets but must be purchased through fishmongers or directly from the oyster farms. The bay’s wild mussels are newer to the market. It is forbidden to farm mussels, as they are considered competitors to the oysters, but wild mussels and other shellfish may be caught and sold.

We sampled the native mussels “au Roquefort” at a restaurant on the bay. They came in massive quantity, in enormous black cooking pots. They were small but flavorful, and a large spoon was provided to eat up the leftover sauce: crème fraiche, shallots, white wine and feisty blue cheese. They made a rich and satisfying meal.

We’d recommend them any time, any way — but best enjoyed, we concluded, at a table on the waterfront with a warm, salty breeze swirling around the shoulders, flags flapping on the pier, while one’s fellow diners chatter away in French and the sun sinks slowly into the sea. Perhaps not the easiest list of ingredients to assemble, but it’s the perfect recipe for feeling like the world’s your oyster.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2023 World edition.