Every time I write about electric cars, there is an explosion of hostile comments online in which readers angrily denounce electric vehicles and the people who drive them. Much of this animus rests on a plausible yet mistaken assumption — that EV owners are all passionate environmentalists, sanctimoniously swanning around in their zero–emission vehicles while disdaining the ghastly, planet-killing masses burning dinosaur juice.

Let me disabuse you of this. That stereotype was perhaps partly fair when applied to the Toyota Prius — although even then I suspect it concerned only a minority of owners. In the case of fully electric cars, however, I would be willing to bet there is no correlation between tree-hugging beliefs and EV ownership — if anything, the correlation runs in reverse. The modal electric car buyer does not give a damn about the planet: they are buying electric cars because they like technology, or because they like cars, or both. You may imagine they are eyeing your tailpipe with disapproval — in truth the typical electric car driver doesn’t care what car you drive: they are too busy enjoying their own car, and for entirely selfish reasons. This is as it should be.

There is an Aesop fable called “The Farmer and His Sons” in which a dying landowner tells his sons not to divide the family land, since a treasure lies hidden somewhere beneath it. After his death, they dig over every inch of the land in search of the promised riches, but come up empty–handed. Only when the resulting crops grow abundantly do they realize they have been tricked into doing the right thing for the wrong reason. All the while they had been greedily searching for treasure, they were inadvertently plowing the land.

A certain section of the environmental movement is obsessed with obtaining environmental ends by signaling self-sacrifice and general hair-shirtedness. That may be necessary at times, but (as Aesop’s farmer knew) it’s best not to appeal to sacrifice and self-denial until you have exhausted the possibilities of self-interest first. It is the consequences of a behavior that matter, not the motivation.

And nearly all technological change is driven in its earliest stages not by high-minded purpose but by the selfish pursuit of novelty. (If you sell products on their environmental credentials, it may backfire, since people assume there are trade-offs, and infer that any detergent that is “kind to the planet” is correspondingly worse at cleaning your clothes.)

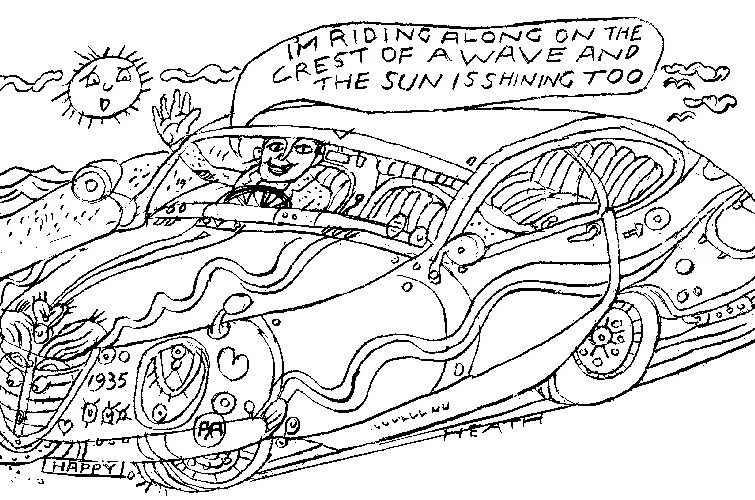

So if you want to sell electric cars, don’t try to appeal to George Monbiot — try to appeal to the inner child, to the simple fact that they are fun.

Recently I was lent a Microlino to drive — a tiny Swiss two-seater electric car modeled completely on the Isetta bubble-car of the 1950s, with the same potty single door opening at the front. It has a range of seventy miles and a top speed of 56mph. My verdict? Well, first of all, as a city car it is quite superb. It is also spectacularly fun — not only for the driver but for spectators. In fact, so much happiness did it bring to people on the street that I felt compelled to drive it around gratuitously out of a sense of pure altruism. It is insanely cute. You would attract less attention in a Lamborghini.

I had always grudgingly accepted my friend Stephen Bayley’s argument against electric cars — that there was an aesthetic quality to gasoline cars which EVs could never match. Having driven the Microlino, I’m not so sure. In its miniaturized form, an electric car can be truly delightful. Indeed, Stirling Moss’s last ever car was a Renault Twizy.

Besides, if there is one old technology worthy of preserving for aesthetic reasons, it is not the internal combustion engine. It is the steam locomotive.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply