Asparagus inspires gentle thoughts, or so said Charles Lamb in an essay about grace before meals. Other vegetables had come to pall on him, but a noble affection for asparagus still lingered in his heart, a reminder of simpler and more innocent times. One can only surmise that he didn’t much care for the vegetable. Who feels melancholically virtuous when eating greens? People who don’t really like them, that’s who.

The rest of Lamb’s highly amusing spoof on cultural puritanism is devoted to arguing that feasting, jollity and profusion of edibles — particularly meat — are unspiritual and at odds with the praying of grace: “fit blessings to be contemplated at a distance with a becoming gratitude; but the moment of appetite (the judicious reader will apprehend me) is, perhaps, the least fit season for that exercise.”

The essay is worth dipping into, even though it does leave delicious asparagus damned with faint praise. Lamb is not the only one to view the green spears with a jaundiced eye, of course, and there’s no use arguing about taste. Even so, can he have tried it with a delicious mousseline? He wouldn’t have been able to say a puritan grace before that, for it’s truly delicious.

Everyone talks about asparagus and hollandaise sauce, but in my view mousseline, a more delicate spin on hollandaise, pairs better with the subtle flavor of really good asparagus. It’s also great fun to make. Ever since a high-school chemistry class in which we had to whip up our own mayonnaise by hand to demonstrate the principle of emulsification, I’ve loved recipes that require you to incorporate fats into egg yolks and produce an entirely different substance. Once you’ve got the technique figured out, a whole realm of delicious and impressive sauces are yours for the whisking.

Mayonnaise is one of the five mother sauces of French cuisine, codified in the nineteenth century by chef Auguste Escoffier (the others are béchamel, velouté, espagnole and tomate). As a mother sauce, mayonnaise rejoices in a large and delightful number of offspring; her most famous daughter is hollandaise.

Once you can make hollandaise, you can make all the other sauces based on the same technique: béarnaise, maltaise, bavaroise, mousseline and the rest. In its most basic form, hollandaise requires the cook to put anywhere from one to four egg yolks into a double boiler over simmering water. You whisk steadily so the egg yolks stay smooth and gradually thicken, turning silky and pale yellow in the process. If it’s too hot or if you don’t whisk them properly, they’ll turn into scrambled eggs, at which point it’s time to cut your losses and start over.

If you don’t succeed immediately, let Winston Churchill be your inspiration for perseverance and do not give up. Never, as he might have said, yield to the apparently overwhelming might of the temperamental yolk. Once you’ve recognized the precise turning point at which the yolk begins to thicken, victory is yours. Off goes the heat, and the butter and an acid ingredient — usually lemon juice — are whisked in, a little at a time so the egg yolk can coat each fat molecule and glue it to its neighbor in a sort of happy hollandish oneness.

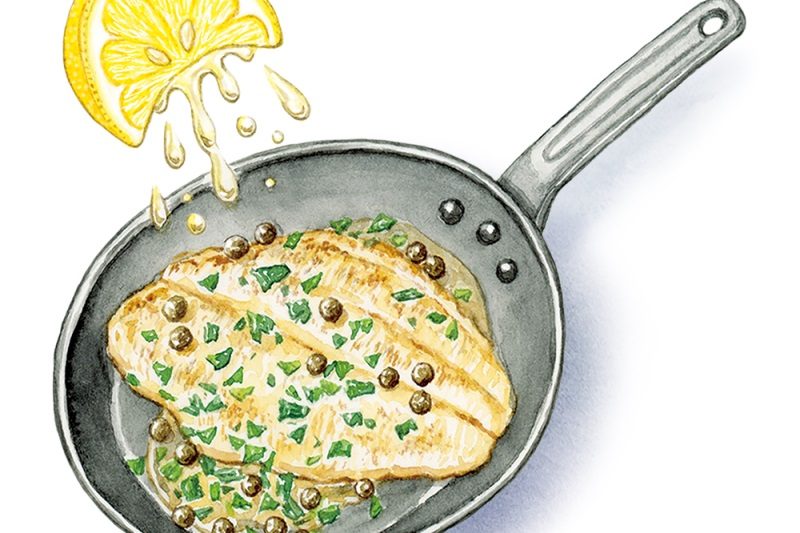

Béarnaise sauce simply exchanges the lemon juice for a pungent vinegar reduction, made by boiling down white-wine vinegar with shallots, chervil, tarragon and cracked peppercorns, and then straining the results. It is a personality-filled sauce that goes well with meat and fish. Sauce maltaise uses blood-orange juice and zest for the acid component, and is often served with fish, broccoli and asparagus, though in my opinion mousseline remains the superior choice.

Mousseline means muslin in French, and the sauce is supposed to be as light and airy as the fabric after which it is named. It follows the classic hollandaise recipe, but at the end whipped cream is carefully folded in, giving it a delicate, voluminous texture. Served alongside tender young spring asparagus, briefly blanched — the ancient Romans had a saying, “as quickly as it takes to boil asparagus” — it’s perfection.

May one, or may one not, eat asparagus with the fingers? The Romans come in handy again when discerning this point: when in Rome, do as the Romans. This is no fun for the manners police, who are never happier than when scandalizing the world with something that looks terribly rude but is in fact an insider status symbol — eating peaches with fork and knife, for instance, instead of biting into them like apples. (This is actually not at all a bad idea, considering the extremely high likelihood of peach juice dribbling down the chin and potentially staining a favorite blouse in cases where the apple-like approach is adopted.)

However, in defense of those who delight in obscure rules of politeness, etiquette experts say that asparagus served alone, without sauce, is technically a finger food. But they’re not really wholehearted about it. They add all manner of cautions about allowing vinaigrette or sauce to drip, the social ineptitude of lifting an overcooked and drooping stalk into the air, and what to do if you reach the end of the asparagus only to realize that the cook neglected to chop off the tough section in the kitchen (apparently, you’re supposed to chew it for a bit and then set the stringy remainder on the edge of your plate). Perhaps best to err on the knife-and-fork side, thus sparing oneself navigation through a veritable field of social landmines.

Asparagus is one of the first vegetables that can be harvested in the spring. Its name is derived from the Greek for “to spring up,” and it is a symbol of springtime and renewal. What more appropriate, or tastier, accompaniment could there be to the Easter lamb? Whatever gentle thoughts the Lamb named Charles may have held about the vegetable, mousseline sauce will lift it into the realm of delight. And in defiance of culinary puritanism, the feast-day grace can be proffered by fleshly body and spiritual soul as one — held together, thanks be to God, by food, glorious food.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2023 World edition.