The best teacher I ever had in graduate school — or anywhere else, for that matter — was also the most dedicated. Most semesters he would offer a not-for-credit seminar one evening a week at his house. There, some half-a-dozen fledgling philosophy students would congregate, bottle of German wine in hand, to parse slowly through one text: Heidegger on Nietzsche, say, or Bishop Tempier’s condemnation of 219 propositions in 1277, a once-famous event that signaled the eclipse of the Aristotelian world view in favor of the Christian. We devoted one full semester to De li non aliud, “Concerning the Not-Other” (i.e., God) by the mystically inclined Renaissance philosopher, churchman and diplomat Nicholas of Cusa (1400-1464). (That “li” — “the,” more or less — will be of interest to Latinists, since it is a late gift to the language.)

Cusanus (to given him his Latin moniker) is not exactly a household name. Still, a couple of his phrases have secured a place in the lexicon of higher chit-chat: “the coincidence of opposites” was one of his, as was “learned ignorance.” Cusanus is not for sissies. A typical sentence: “The Absolute Maximum, with which the Minimum coincides, is understood incomprehensibly.” Indeed, or as Francisco said in another context, “For this relief much thanks.”

In case you suspect you have wandered into the wrong column, I hasten to remind you of my sly introduction of the phrase “German wine” in the third sentence. We students showed up with German wine in homage to our teacher, who was German. In the natural course of things, these weekly academic sessions became mini tutorials in German wine as well. We all learned that German wine was typically low in alcohol (about 7.5-8 percent, usually a bit more for Kabinetts) and that the favored (by far) grape was Riesling.

“Kabinett” on a label usually meant semi-dry table wine. “Qualitätswein mit Prädikat” (QmP) was a badge of honor for better wines, as was an asterisk or gold capsule. Qualitätswein bestimmter Anbaugebiete, or QbA, was a step down.

We learned that “Spätlese” meant “late-harvest”: sweeter, more complex wines. “Auslese” meant later and sweeter still, and “Berenauslese,” “Trockenbeerenauslese” and “Eiswein” (from frozen grapes) meant very late and usually very expensive dessert wines that, like Sauternes and Tokaji, had a close working relationship with Botrytis cinerea, the fungus that either ruins or perfects certain grape harvests.

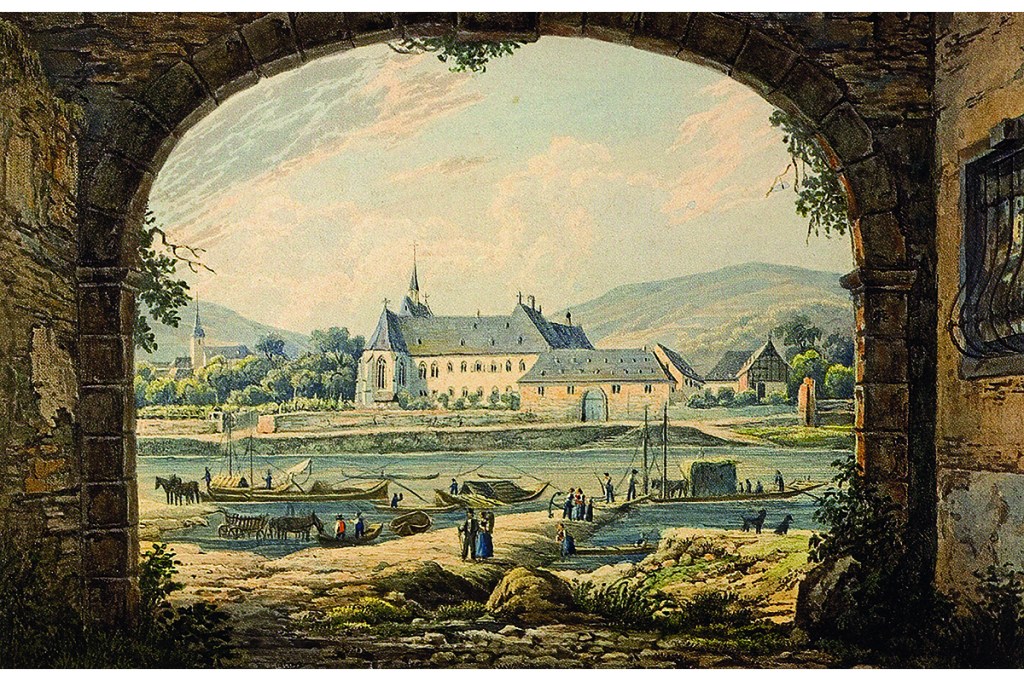

OK, but why drag in Nicholas of Cusa? I was waiting for you to ask. One of the things I remember from that seminar was our teacher’s remark that one of Cusanus’ worldly, practical actions was to endow an old folks home in his native town of Kues with vineyards. That was in 1458. The vineyards were the hospital’s primary asset. They still are. Situated midway down the snake-like Mosel River, the area is now home to some of the very best German wine.

The Cusanusstift owns about forty-four acres of steep, slate soil vineyards across from the towns of Wehlen and Brauneberger in an area with the romantic name of Sonnenuhr, “sundial.” Their motto is “Wein trinken und Gutes tun”: “Drink wine and do good.” What’s not to like?

I have been trying to sample wines from this renowned Weingut for years. Finally, I discovered that the Winchester, Virginia, importers Kysela Père et Fils carry some of the Cusanus wines. Through the intercession of friends, I was able to get several bottles of Cusanusstift Spätlese as well a generic Riesling, a Kabinett and a Spätlese from a hip neighboring vineyard called Bastgen, a nineteenth-century property owned since 1993 by the husband-and-wife team of Armin Vogel and Mona Bastgen.

All the wines were from the 2021 vintage, a year that started cold, whose middle was very wet, but whose finish was long, dry and warm. Harvesting went on until late October or even early November. It was a classic German year: difficult but rewarding. (As Spinoza observed at the end of the Ethics: Omnia praeclara tam difficilia quam rara sunt: “All things excellent are as difficult as they are rare.”)

A group of us serious thinkers gathered one late January afternoon at Gotham Restaurant, my other office, and sampled two St. Nikolaus Wehlener Sonnenuhr Spätleses, one with the coveted asterisk, and a St. Nikolaus Brauneberger Juffer-Sonnenuhr Spätlese, all about $32, a steal. We also tasted those three Bastgen wines, which ranged from $23 for the generic Riesling to $34 for the Spätlese. All were elegant and well-made, and the Spätleses from the Cusanusstift had a meditative, sunny and fortifying depth. I hope those pensioners on the Mosel are allowed to drink some of the wine that supports them.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.