“Am I gonna die today, Treen?”

I kissed his cheek.

“Darling, your oxygen, blood pressure and pulse are fine and you’re a good color. Since you woke up you’ve had a poached egg on toast, plain Greek yoghurt with berries, granola and maple syrup, a Snickers bar, a piece of fruit cake, a baked fresh mackerel with tomatoes and a Mini Magnum. It’s two o’clock — if you do die it’ll be from gluttony.”

This was early May. Jeremy, paralyzed from the chest down, was attached to three syringe drivers for pain control and had a urinary catheter in situ. A few weeks earlier he’d told me and the local doctor he wanted to die at home in our bedroom, with its spectacular views south towards the Massif des Maures. Dr. Biscarat agreed that Jeremy spending his last weeks up here with me, nestled into the cliff, surrounded by his books and with nightingale song drifting in the windows would be an undeniably better option than hospital — if palliative care could be arranged and I could cope. It could. I would.

Because the bedroom is so small, our double bed had been pushed against the clothes cupboard door to make way for the hospital bed. I wore the same two pairs of jeans and four T-shirts for weeks. There were only a few inches of clear space between the hospital bed and cave wall. Electric cables were taped to the floor. Caring for Jeremy in such a confined space was difficult. Our bed became a nest and office for me — and the nurses’ and carers’ work station. Apart from sprints to the kitchen, bathroom, washing line and bins, I spent twenty-four hours a day in that room for seven weeks. To reach and empty Jeremy’s catheter I had to crawl under the jutting rock wall. I did this several times a day. Once I forgot to close the catheter and when I next cradled Jeremy as he turned to be washed by the carer the bag leaked over my Ugg boots.

“Sorry sweetheart.”

More kisses. “Don’t worry. Not your fault. It’s me. I’m tired. They’re ancient anyway,” I said, mopping up to save the books on the floor beside the bed.

A lifetime ago in July 2014, the day before the Spectator summer party, Jeremy and I walked along the South Bank towards the Oxo Building. On the way we bought a copy of Philip Larkin’s Whitsun Weddings at a stall. Later, in the bar having a drink, we sat very near but not touching, Jeremy turning the pages while we read. When we’d finished he closed the volume and looked into my eyes with such intensity I had to look away. Then he said: “Is there a dealbreaker?”

“OK… please don’t shout at me…”

He laughed. “That’s easy.”

“I’m quite boring really compared to your other girlfriends. I’m wondering if that might be a dealbreaker. Or something else?”

“You’re not boring.” He held my hand. “My go. You’ll need to be forgiving.”

And so it began. Tentatively at first, as both of us were bruised by the past. But soon we began to fall or rather — paraphrasing Low Life — to double-somersault into love with a half-pike and a twist.

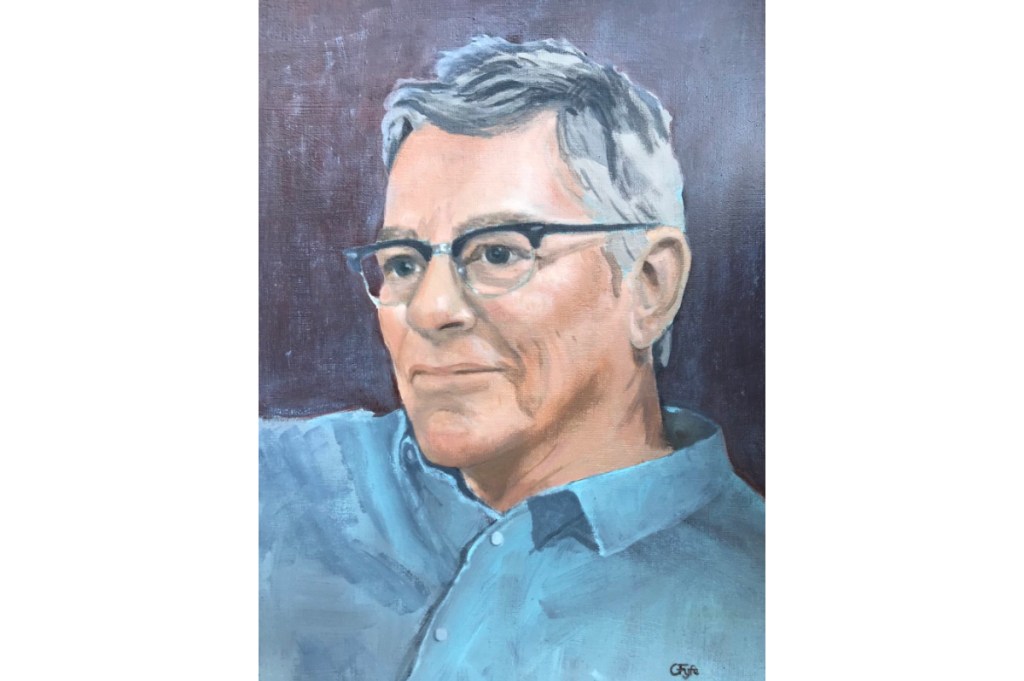

Later that year, for reasons too complicated to explain, I moved to France. It worked. Jeremy stayed in Devon writing, reading, looking after his mother and helping with his grandsons, but visited often. He’d had brachytherapy by then and was on hormone treatment so he wasn’t drinking much. Happy days they were. Always interesting, Jeremy was quietly spoken, modest, considerate, kind, passionate and loving. He was a great laugh and a terrific dancer. We had a blast. He encouraged me to paint and helped me write, things I’d wanted to do all my life. “This is your time,” he’d say.

One wet afternoon he told me he’d found two passages from Virginia Woolf he’d like to read to me. The first was from the memoir Moments of Being, describing a poignant visit back to Talland House in St. Ives, where Woolf spent idyllic childhood holidays. The second was from To the Lighthouse, about a character painting a seascape from the garden. My childhood home, a farmhouse in Scotland, lay derelict for years after we left when I was eleven, and as a teenager I’d often take a train and walk miles through the Renfrewshire countryside to visit. I’d climb through an unlocked window and wander from room to room leaving my beloved and long-dead father’s study till last. Both passages Jeremy chose carefully and read beautifully. Minutes later he was engrossed in his phone. I asked him what he was watching. “It’s the British Travelers’ bare-knuckle heavyweight boxing championships. Look,” he said. How could anyone fail to love Low Life?

A few years later, Jeremy’s grandsons moved to the other side of the country and in 2019 Jeremy’s mother died. He had to leave the house in Devon he’d lived in for thirty years, and in January 2020 found a cottage to rent in Wiltshire at a reasonable price. He planned on traveling back and forwards between England and France as he pleased. It seemed the perfect solution, but the cottage was cold and damp. He was lonely there. Later that month, following a travel jaunt to the Bahamas and a few days at the cottage, he came back to France. Permanently it turned out, thanks to Covid and his deteriorating health. We didn’t really discuss it. After a couple of months he told me the rest of his stuff was arriving in a van the following week. The delivery included a great northern diver and a buzzard in glass cases, and another 2,000 books. The cave house was already full, so most of the books and clothes had to be stored in the rough cave next door, which has a door but no glass in its small windows.

Jeremy was complicated. Periodically throughout his life he suffered from depression. His astonishing powers of observation and perspicacity, which helped him write some of the funniest and most beautiful sentences in the English language, occasionally tipped into periods of mild paranoia and despondency, after which he’d apologize and return to his cheerful, funny, fascinating, brilliant and brave self. He was easily bored, sometimes by me, and I did have to forgive his unkind words and hasty judgments now and again, but he never shouted at me. He was a star and I’m lucky to have shared my life with him for so long. We thought we’d have two years. We had almost nine. His last words were to me, the afternoon before he died: “We can all live happily ever after…”

The Spectator is holding a memorial service for Jeremy Clarke at St. Martin-in-the-Fields in London on Monday July 10. If you would like to attend go to spectator.co.uk/memorial for more information. You will also be able to watch the service live. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.