‘Nothing will ever be the same again.’ You hear a lot of that glibly categorical punditry around the COVID-19 outbreak. Already, the progress of a mindless virus through the human population is being touted as the herald of the reorganization of the world’s economic system and the end of neoliberalism, the harbinger of a world in which nurses and shelf-stackers are valued more highly than investment bankers. Well, we’ll see. There are, as has been often said, two great things of which we can always be certain: death and taxes. The former is currently enjoying a bit of a moment. But the latter, sooner or later, is going to make the sort of roaring comeback not seen since First Blood Part II.

It’s worth thinking, at the social level, what all this will mean for our ways of interacting, our modes of feeling, our methods of doing business. In the first place, it’s very unusual for modern families in the West to spend all day, every day, at home together. Anecdotal evidence from China suggests that we can all look forward to a surge in post-lockdown divorce cases as ill-matched couples, freed from each other’s company, rush to make sure that there’s no danger of that happening again. We’ll have to wait nine months or so to see whether better-matched couples have responded to confinement in a different way. When partnerships are tested, some will likely break and some grow stronger.

Another bromide is that ‘we’re all in this together’. This is true in a trivial sense and not true in a deeper one. The trivial sense: the virus can infect anybody, regardless of wealth or rank or geography or political alignment. Sen. Rand Paul — to say nothing of the UK prime minister — public-spiritedly reminded us of this point by contracting COVID-19. Those screeching and whooping on social media along the lines of the old political sectarianisms — MAGA-swarming the ‘Democrat hoax’ about the virus, or baiting liberals about their love of open borders — are starting to look like the generals who relied on cavalry charges in an era of barbed wire and the Maxim gun. They’re clinging to the old ways because it’s comforting perhaps. But those old ways, at least for now, belong to a vanished age — the age of six weeks ago.

That said, social distancing and lockdown do not affect people equally. The effects stratify by class, race, professional sector and age. For childless white-collar freelancers of an antisocial bent, six months confined to quarters won’t represent too much of a gear-change at all. But families whose breadwinners work in the hospitality industry or the performing arts, in trampoline parks or in now-shuttered factories making nonessential widgets, have seen their incomes go to zero. Those who work in hospitals risk infection and death and will likely spend the next months separated from their families. Moneyed middle-class parents may be tearing their hair out at the disagreeable novelty of having to clean their own houses and look after their own kids; the cleaners and nannies who used to perform those roles have rather more to worry about.

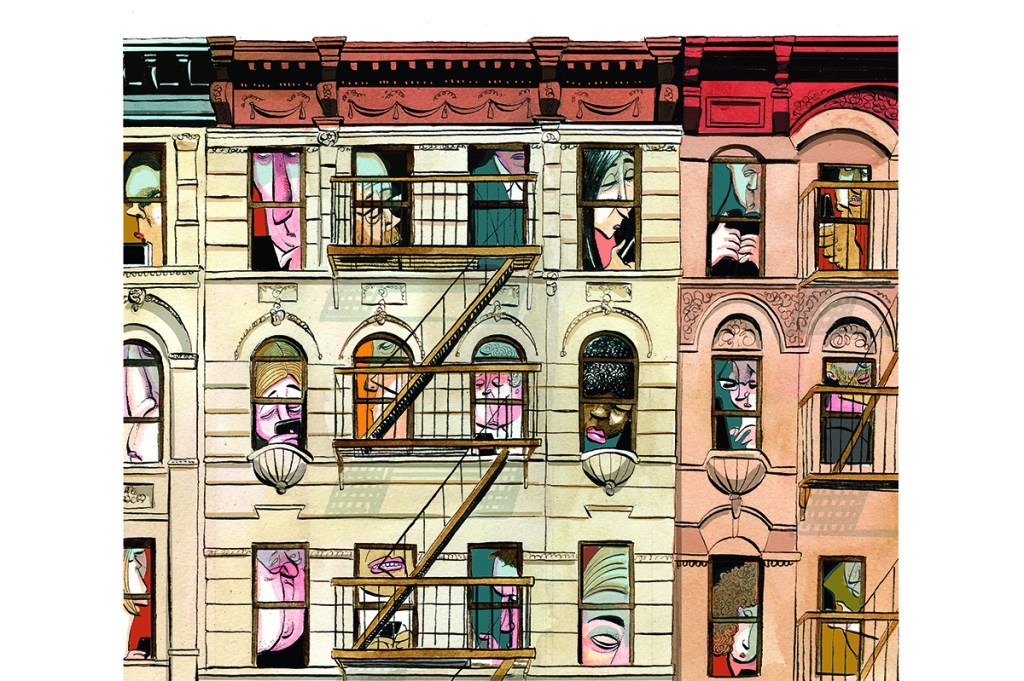

Those with bigger incomes who don’t live week to week can afford a big raid on Whole Foods or Costco to tide them over. Others can’t. Those who live in comfortable-sized houses with their own gardens and their own virus-free front doors are in a different situation to those in one-room apartments on high floors of shared blocks. There’s justified anxiety about victims of domestic violence cooped up with their abusers (Seattle police have reported 22 percent more calls about domestic violence incidents compared with this time last year), about the mental health of those in isolation, about disabled people struggling without carers. Every one of the little silos of our social setup is challenged in its own way, from the inconvenient to the inconceivable.

And age, too. The elderly and infirm not only have greater cause to fear the virus itself: they have, potentially, a much harder time of confinement. Often they will be alone. They will have to do without their usual carers, or fear every time a carer comes to their home that they will bring COVID-19 with them. And while the middle-aged may — other circumstances aside — find it tolerable to put their social lives on hold, the young will take a different view. It doesn’t mean that much to me to forfeit the summer of my 47th year, but to forfeit the summer of your 17th year, for those in whom the ‘sap is rising’ rather than clotting in the ever woodier xylem, will feel like the end of the world. A friend of mine reports that her daughter is about to turn 13: ‘The poor kid will have to spend her first birthday as a teenager with her massively uncool and very boring parents.’

These experiences have drawn lines through our society that, I think, will last. They will be remembered. They will, in some way, fester. Not in the comparatively shallow way that we’ll argue actuarially over economic unfairnesses — arguments over those who fell through one or other of the governmental safety nets or profited from hastily put-together measures designed to help the less well off. More that the gaps and stitches in the social fabric have been exposed by this crisis: the profound ways in which we’re not in it together, or not in the same way. Perhaps that means, we could say optimistically, that we’ll start to mend those gaps and tighten those stitches, but I wouldn’t bet on that being as thorough as we might all hope, especially not if the federal bailouts find their way into the pockets of CEOs.

In some ways, though, this could be worse — at least in the developed world. Imagine a global lockdown in the pre-digital age. At least some of us can work from home. Money can still ping around the world, if there’s any left of it. So can information. And those of us who can’t work from home, or who are out of a job, are at least able to feel connected, to stay in touch with the news. Boredom is not a trivial thing to deal with; neither is loneliness.

And one thing that the global COVID-19 lockdown really has achieved is the alleviation of a minor public pathology. COVID-19 has killed Fomo, the ‘fear of missing out’. It has abolished, for the foreseeable future, the nagging anxiety that someone, somewhere, is having more fun than you; that while you’re rewatching Breaking Bad on Netflix there’s a wild party going on to which you weren’t invited. There are no parties. Since the pandemic started my wife has become addicted to following celebrities on Instagram — not for an insight into their glamorous lifestyles but the opposite. ‘It’s brilliant,’ she’ll yelp. ‘Look! Mark Wahlberg! He’s at home doing fuck all! And Michelle Pfeiffer — God, she’s beautiful! She’s at home doing fuck all too!’

Six weeks ago I had never even heard of Zoom or Houseparty. Now I conduct my entire social life on videoconferencing apps. Platforms originally designed for large- and medium-sized businesses to conduct bicoastal or international meetings are now where school-age children hang out for recess, where friends have a Friday-night drink together, where extended families have Sunday lunches, where pub quizzes take place and where recovering addicts gather to say the serenity prayer. (Scatter quotation marks through the preceding paragraph as you feel appropriate.)

The atomization of society that some predicted as a hallmark of the internet age is happening, and not happening. But in the present circumstances it’s doing both of those things faster. Digital media have given us the ability to be connected to each other in ways we never were before, and with an immediacy we’ve never had before. But at the same time they isolate us in myriad ways. There should be a German word — there probably is; if not Ben Schott will doubtless invent one — for the connected solitude that is a hallmark of our wired age, and the gentle tristesse and disorientation that attend it.

A quirk of this I sometimes return to is the way in which, a few years back, I rekindled friendships with people I never saw in real life — some on the other side of the world — through the online game World of Warcraft. I spent hours a day chatting and playing with these pals in a virtual realm, and it really didn’t matter all that much that for the purposes of our interactions they were epicene pointy-eared elves or paladins with giant war-axes and chromium-plated disco-tits. But there again, in meatspace I was basically eating instant ramen at 4:00 a.m. in a cloud of cigarette smoke in my solitary room, and when the computer went off I was at once alone.

And I think of Chris Ware’s magnificent graphic novel Building Stories, in which some of the most poignant scenes evoke the flipside of that connected/alone combination. A couple sitting at the kitchen table together, both lit by the glow of their laptops. Or a woman standing naked by a bed, looking sad, while her husband lies on the bed, oblivious to her presence, zoned in on the iPad that rests on his chest. Even in lockdown, this side of it applies. Will we watch a movie together at the end of the day? Or will we — as the kids would prefer — scatter to different parts of the house to play separately on our various gadgets?

When we emerge from all this we will have settled into new habits, new grooves. That will be structural. The discovery that many forms of work can be done from home will surely accelerate something that was already, albeit sluggishly, happening: businesses will find that paying exorbitant rent for office space is something that need no longer be taken as a given. Presenteeism will likely become a quaint anachronism, and the short-contract, remote-working, part-time economy will blossom like duckweed on a pond.

It will also be personal. We’ll rebound, I dare say. We’ll start to value facetime in a way we never properly did before FaceTime. We’ll house-party — not Houseparty — like it’s 1999. But we’ll be doing that, just slightly, against the pull of a new gravity: the realization that our links to each other are just that bit more digital than before, that families live in houses and the members of families live in rooms, and each of us is most securely connected to the world not by analogue conversation, but by the wireless router in the corner of the room: connected, and alone.