Trivia time. Put down the magazine, look away from the page and name as many green liqueurs as you can.

Well? Did you get crème de menthe? Award yourself a point.

Absinthe? Sorry, no point; absinthe contains no sugar, and is therefore a flavored liquor, not a liqueur. Note the difference in spelling: liquor can serve as a base to which sweeteners and flavors are added to form liqueur, but technically the one is not the other, and the other is not the one.

What about Chartreuse? If you guessed it, well done: the Queen of Liqueurs claims the distinction of being the only naturally green-colored liqueur in existence. Its verdant hue is drawn from the chlorophyll in 130 varieties of herb and plant, macerated in alcohol in keeping with a 16th-century secret recipe belonging to the least-talkative monks in the world: the Carthusians of the Grande Chartreuse, whose silent, white-walled monastery is snugly hidden high in the French Alps.

You could spend a hundred years trying to reproduce Chartreuse without the recipe, and you would probably fail. Some Midas-like geniuses, like Shakespeare, can’t seem to help dripping brilliance like rainwater on everything they get near, and you’re left wondering if their biggest hits were deliberately planned and executed, or if, o felix culpa, they happened by mistake, the happy result of an enormously gifted personality with so magnificent an inner world that when it spills over into reality, he doesn’t even realize how incredible what he’s doing is until it’s done.

There’s no way Shakespeare developed his sonnets like an engineering project, though their engineering is flawless. I imagine he had to work at parts of them, but their fugal brilliance, plucking imagery and language and sound, like so many flowers casually encountered on a stroll and just sort of accidentally getting a single dazzling bouquet, can be only explained one way: the guy was a natural. It simply welled out of him. Chartreuse is like that: the golden-green liquid the monks bottle up and send out into the world beyond their walls is not exactly an accident, but certainly an afterthought, a casual byproduct of the genius and the rich inner life of the Grande Chartreuse, dripping down into casks from the higher plane on which they live, up there where the air is rarefied and only superhuman lungs can handle the oxygen levels.

But what a byproduct. You might fairly call it sweet, spicy, pungent, well rounded; when sipping it on ice, as the Carthusians recommend, you may detect, among other notes, lavender, citrus, oregano, peppermint, star anise, verbena, ginger, pine, fresh basil and chocolate. Mixing it brings out other tones. Lime juice, for instance, activates a whole new circuit of flavors, as in the popular Last Word cocktail, which combines gin, Chartreuse, maraschino liqueur and lime juice.

You can also add Chartreuse to Champagne, as the Plaza Hotel in New York City did in the Moët Imperial Gatsby. Soak one sugar cube in a quarter-ounce of green Chartreuse in the bottom of a flute; add five ounces of chilled Moët Imperial and one spiral lime twist. Sounds elegant, but perhaps a little too sweet.

However, never let it be said that I refused to hear both sides of the story. If the Plaza Hotel wants to prove me wrong, vouchers for a complimentary visit (or cases of Moët Imperial) can be sent to me c/o The Spectator, and I promise to bring my keenest analytic faculties to bear on the matter. (Freddy, any bubbly arriving by special messenger is for the Food & Drink section; don’t let the Books & Arts people get their paws on it.)

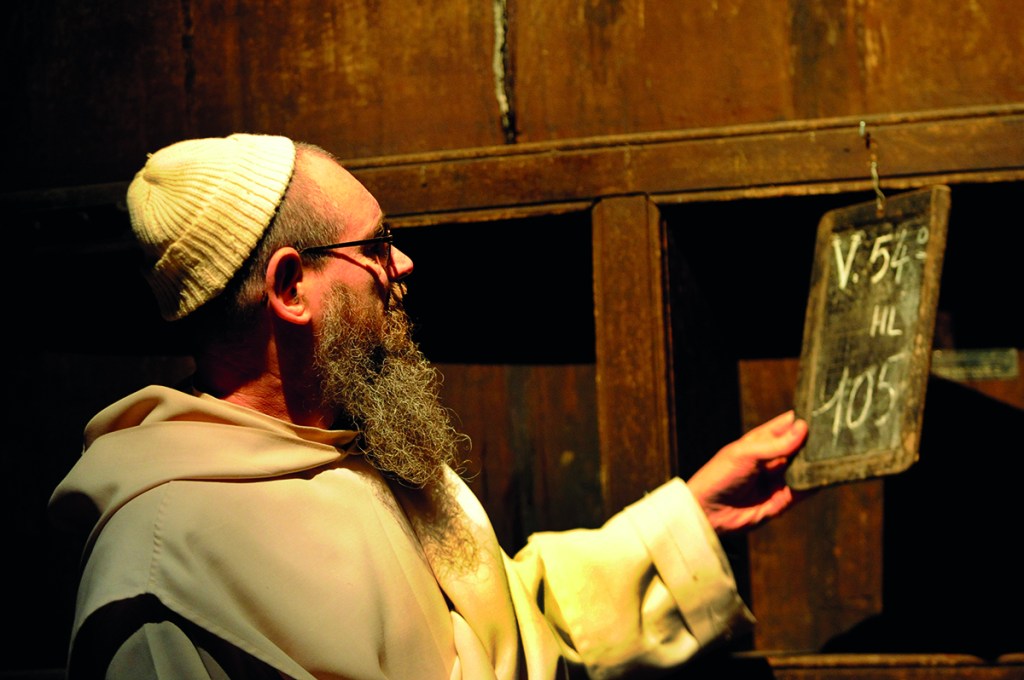

Champagne and The Great Gatsby might seem odd companions for a liqueur made by the most austere monks in the world. No socialites, they; no visitors may enter their Alpine refuge, and the road stops a good distance from the monastery, so that passing vehicles do not break the silence. A sign along the footpath warns the day-tripper who would approach the outer walls: ‘ZONE DE SILENCE’, with a picture of a monk in voluminous robes and a pointed hood. Even the airspace above the monastery is off-limits to low-flying aircraft. Silence is their treasure, and they guard it jealously.

As documented by the nearly wordless, critically acclaimed film Into Great Silence (2005), the monks almost never speak. They spend their days in prayer, manual labor and sacred study. They eat no meat; fish and eggs are their dietary highlights. They sleep only for three or four hours at a time, rising in the middle of the night for long stretches of prayer.

And they certainly don’t drink their own Chartreuse. They make it and sell it, as they have done for centuries, simply to cover the costs of their way of life.

Isolated as they are, the monks are nonetheless animated by an intensely social spirit, which is why I don’t think they’d mind people pouring Moët Imperial over Chartreuse-soaked sugar cubes (at least in moderation).

When they leap out of bed at 11:30 p.m. and prostrate themselves on the cold monastery floor, one of their nightly tasks is to present the needs of each human being to the Almighty — the Gatsbys, Nicks and Daisys just as much as the rest. The idea is that God will listen more carefully to these members of the spiritual special forces, who daily prove the sincerity of their hearts by loyally sticking to their arduous way of life, and pour down mercy of both the invisible and the visible varieties. If you’ve never tried Chartreuse, invest in a bottle and you’ll agree with me: it’s definitely a gift from heaven, courtesy of the sons of St Bruno.

It is a healing gift as well. Chartreuse started out as an ‘Elixir for a Long Life’, a 138-proof (69 percent alcohol) herbal tonic that is, still sold today as Elixir Vegetal de la Grande Chartreuse, and sometimes used — in France, at least — as a home remedy for minor ailments. A milder and sweeter Yellow Chartreuse, 80-proof (40 percent alcohol), which reportedly owes its color to saffron, is also on the market. But the most popular version remains the classic Green Chartreuse at 110-proof (55 percent alcohol).

This was the variety commended by Anthony Blanche at dinner with Charles in Brideshead Revisited: ‘Real g-g-green Chartreuse, made before the expulsion of the monks. There are five distinct tastes as it trickles over the tongue. It is like swallowing a sp-spectrum.’

The ‘expulsion’ that Anthony Blanche refers to occurred in 1903, when the Carthusians were forced into in exile by the violently anti-clerical French government. The government had deemed most contemplative orders useless and, green (or possibly chartreuse) with envy, proceeded to purloin their property.

The Chartreuse trademark was sold to a private company, which promptly went bankrupt. Honesty, it would appear, is the best policy, especially when it comes to dealings with the holier in our midst. Friends of the Carthusians bought back the trademark and returned it to the monks when they regained their monastery in 1940. I expect the world’s most laconic monks thanked them, but in as few words as possible. Speech may be silver, but silence is Chartreuse.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2021 US edition.