South of France

Throughout the flat, post-Christmas limbo I lay languishing after another dollop of chemotherapy and read my Christmas present, Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, in the later Everyman translation by John E. Woods. Set alongside H.T. Lowe-Porter’s sturdier pre-war translation, the difference was more marginal than I’d been led to believe by John E. Woods’s online trumpeters, and in many cases the old workhorse H.T. Lowe-Porter’s choice of words was more graceful and economical. Or so it appeared to this particular unwashed, unshaven reader with food stains on his pajamas, drugged up to the gills on morphine, antibiotics and Domestos, or whatever it is the nurse dripped into the tube opening in my neck. But on every page there came a word, phrase or sentence in the new translation that was as deft and incisive as a through ball by Luka Modric struck with the outside of the boot, so I stuck with that.

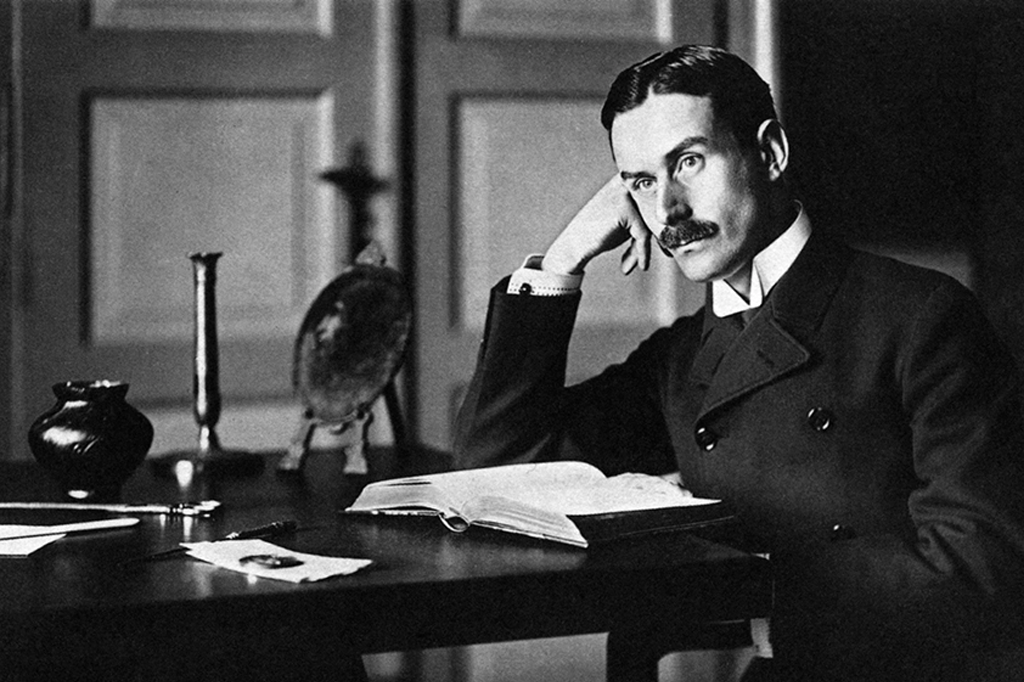

Thomas Mann: what a serious guy! And so far into the closet he had a grace and favor apartment at Cair Paravel. But I love that diabolical, Dionysian final 10 percent in him. The Magic Mountain is set in a Davos sanatorium before the Great War and through his characters Herr Mann says things like: disease takes one to an ecstatic anticipation of death. And: health makes people stupid. And: all disease is caused by the libido — it’s a form of immorality. Ideal reading, then, for we ecstatic diseased.

I hope I’m not boring you?

On New Year’s Eve Catriona flew up to Bonnie Scotland for a week to visit her three grown-up daughters and brand-new darling grandchild. Although alone suddenly, my febrile, diseased consciousness wasn’t aware of any longing for the company of other human beings. Thomas Mann and Kanda Bongo Man on Spotify, taken in combination lying down, provided more than adequate company and mental nourishment. I cried off putting in an appearance at neighbor Michael’s New Year’s Eve gastronomic shindig, claiming cryptically that my light was broken. From then on I anticipated with equanimity if not pleasure a week lived inside my own febrile, diseased imagination. I wouldn’t go as far as to agree with Thomas Mann’s suggestion that the healthy are stupid, but when you’re falling apart at the seams, and your mask has slipped, their insouciant vitality and cast-iron self-belief is a constant reproach.

On New Year’s Day afternoon came a knock on the door. I thought it was Fred the postman come for his Christmas box. But standing there was Professor Brian Cox. Every time I go down to Marseille for a shot of chemotherapy, I am examined by a junior doctor, who always asks, finally, casually, paying keen attention to my response: “Any hallucinations?” I tell him alas no, which isn’t quite true because I do occasionally notice small insects out of the corner of my eye which, on closer inspection, aren’t there. For a split second I thought: it’s started. Mine have begun with an imaginary celebrity astrophysicist standing at the door.

The professor was just back from a 100- date world tour. With him was his wife Gia and his son George, aged fourteen, all real enough. George was carrying a freezer bag containing Champagne and cake. The Coxes have a second home here in France’s Dixie, in fact in the next village, and here they were, down for the week. Unfortunately everyone they know is rotten with flu, and Catriona was away, which left a half-mad slippered pantaloon in a cave as their only point of contact and welcome.

I waved them in, put a match to the fire, and handed George my eighteen-inch Congolese panga with which to slice off the top of the first bottle, which we consider to be the only way to open Champagne. George had also bought a packet of Algerian war French military-issue cigarettes, circa 1960, bought from an antique shop. They were surprisingly mild and his father tried one, the first and only cigarette he had ever smoked in his life, he said afterwards.

Since I’ve been on morphine, alcohol has seemed superfluous. However, it was the Feast of Circumcision and I smartly extended my tumbler every time another bottle circulated, and soon I noticed the old familiar cellular alteration. I went upstairs and hauled down the massive Bluetooth speaker and George put on “Yeah” by LCD Soundsystem. Gawd. Pissed now, we danced in our chairs like 1960s stoners away with the fairies. I urged them to get up and dance on their feet but they refused, out of politeness to the cripple, I imagine.

They came again the next day. And the day after that. Thomas Mann’s diabolism in the mornings; Champagne, cake and French Algerian war fags with the professor and his family in the afternoons; nights dreaming I’m suspended over an abyss.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.