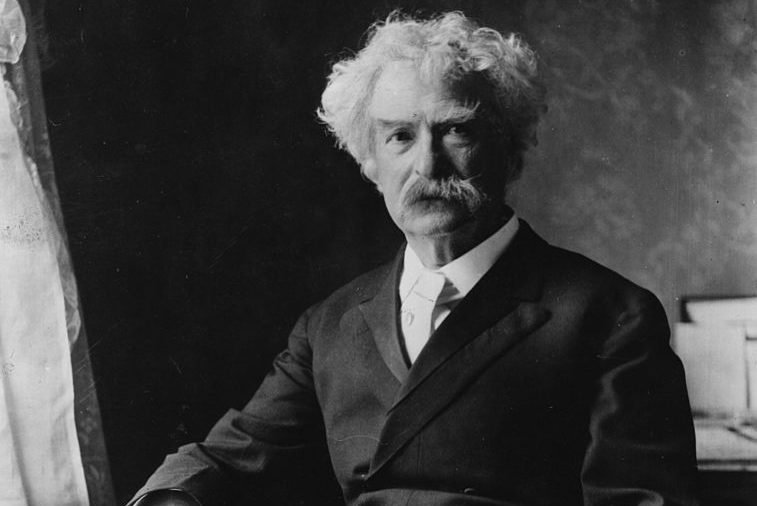

“Irreverence is the champion of liberty and its only sure defense,” wrote Mark Twain in an age before irreverence became a hanging, or at least exiling, offense.

Perhaps the more apt aphorism today belongs to Edward Abbey: “The distrust of wit is the beginning of tyranny.” (The distrust of half-wit, I suppose, is the beginning of a TV critic.)

Mark Twain would be hopelessly out of favor with both wings of the modern duopoly. Militaristic Republicans would scorn Twain for his skepticism of empire and mockery of world-saving cant. (He was a supporter of the Anti-Imperialist League and proposed that the stars and stripes be replaced by the skull and crossbones.) Welfare-state Democrats would choke on such bilious Twainisms as “a maxim of mine is that whenever a man preferred being fed by any other man to starving in independence he ought to be shot.”

Happily, Upstate New York registers as among the most politically tolerant sections of the country, so Twain and his works remain an uncanceled presence up here in God’s country. The Twain industry is centered in his boyhood home of Hannibal, Missouri, of course, but Upstate cities Elmira and Buffalo played significant roles in the life of the writer christened Samuel Clemens.

Folks leave cigars, not spittle, on Mark Twain’s grave in Elmira, hometown of his devoted wife Livy, not to mention the news-reading fabulist Brian Williams and designer of gangbanger garb Tommy Hilfiger. Twain wrote his tales of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn in Elmira — his octagonal writing hut is open for inspection on the attractive campus of Elmira College — but my subject is Buffalo, whose downtown public library boasts a Mark Twain Room whose star attraction is the original handwritten manuscript of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Twain/Clemens called the Queen City home from August 1869 till March 1871 because Jervis Langdon, his coal monopolist future father-in-law, set him up as part-owner and coeditor of the Buffalo Express.

Twain biographers typically dismiss these eighteen months as gelid and miserable, though they were nothing if not eventful: the author married Livy Langdon; was gifted a Second Empire-style mansion on Delaware Avenue, Buffalo’s “Millionaires Row,” by Livy’s father; enjoyed bestsellerdom with The Innocents Abroad; and roughed out the book that became Roughing It.

Buffalo was the place where Mark Twain “decided to stop writing for newspapers and start writing books,” says Tom Reigstad in his meticulously researched and richly informative Scribblin’ for a Livin’: Mark Twain’s Pivotal Period in Buffalo.

Fitfully active and not quite hail-fellow-well-met — a young city editor recalled his boss as “quiet, reserved and irritable” — Twain spun out a column for the Express consisting of one-liners, odd facts, and facetia. For example: “Brigham Young’s mother-in-law is dead”; “Mrs. Lucy Morehead Porter, of Covington, has been appointed Postmistress of Louisville, Ky”; “The river Nile is lower than it has been for 150 years. This news will be chiefly interesting to parties who remember the former occasion.”

He was no slave to veracity, as in his account of “John Wagner, the oldest man in Buffalo — 105 years,” who “recently walked a mile and a half in two weeks… He is to be married next week to a girl 102 years old, who still takes in washing. They have been engaged 89 years, but their parents persistently refused their consent until three days ago.” Wagner, Twain averred, “has never tasted a drop of liquor in his life, unless you count whiskey.”

At election time he twitted his coeditor in words that could be applied with equal justice to pretty much any political pontificator of our time. His thumbsucking colleague, said Twain, will “tell you about these candidates as serenely as if he had been acquainted with them a hundred years although, speaking confidentially, I doubt if he ever heard of any of them till to-day.”

Twain’s departure is often attributed to Buffalo’s snow-spangled winters, but the truth is less flaky. He later wrote a friend: “Our year and a half in Buffalo had so saturated us with horrors and distress that we became restless and wanted to change, either to a place with pleasanter associations or with none at all.”

During the couple’s brief stay on the western edge of New York State, father-in-law Jervis died painfully of stomach cancer; a close school friend of Livy’s, visiting from South Carolina, was taken ill with typhoid fever and died in their Delaware Avenue home; and their doomed first child Langdon was born sickly and struggling. Sickness and sadness and death drove the Clemens family out of paradise. I look at the early snow drifting against a backdrop of bare boughs and slate sky and think of Livy and her choleric husband.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2022 World edition.