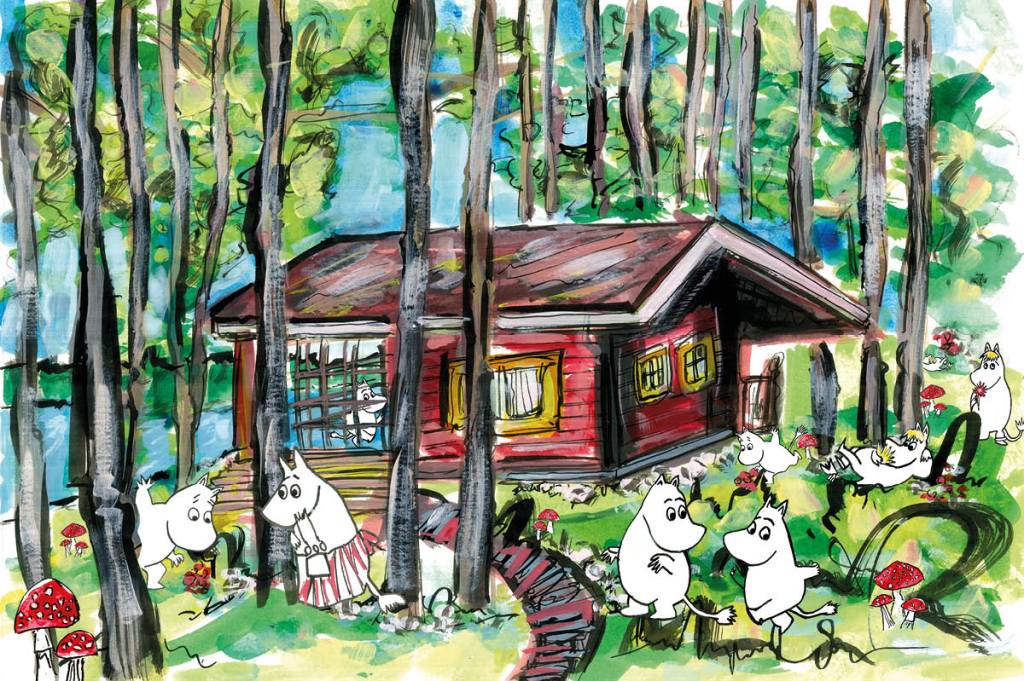

Moomins are synonymous with Finnish life, like saunas, porridge and mökki (summer cottages) culture. The large-snouted white fairytale creatures feature in the Moomin books, which are published in nearly sixty languages. Moomin World, a theme park 100 miles from Helsinki, crawls with tourists come summer — some feat, in a country with roughly twenty-one inhabitants per square kilometer. Moomin merch is ubiquitous too; fans are cult-like in their collection of rare mugs and first editions. Every day, Tove Jansson’s iconography is inked into skin. And it’d got under mine, in a way.

In my twenties, a boyfriend’s collection of paraphernalia from a Finnish former partner quelled any curiosity about Jansson’s imaginary oafs (and Finland). I couldn’t have imagined someday I’d dive headfirst into the subculture, spellbound in the forest, forty-five minutes outside Helsinki.

When I roll up at Hawkhill Cottage Resort next to Nuuksio National Park, owner Annu Huotari wastes no time leading me up a steep hillside.

“The sauna, the forest, the lake. Silence, doing nothing. After two days, I think you will get it. This is mökki life.”

I know she’s alluding to the lofty plans I’d floated over email. I’d suggested every leisure pursuit available, in an apparent effort to avoid sliding into existentialism, brought on by slow living. Horse riding, paddleboarding, and a “sisu” exercise class had made my list. The latter, I was later amused to discover, translates to “stoic determination.” Perhaps indulgent melancholy was preferable.

We pass a wall of equipment laid out for people to borrow, from snowshoes to paddleboards and fishing rods. A whimsical sign points the way to Taidepolku Art Trail, and I duly wind through birch trees, regretting my choice of city boots as I navigate the spongy, rock-strewn forest floor.

Picture frames are hung on tree trunks, a moss-covered troll plays a guitar knowingly painted with a rainbow swirl. “Everyone is welcome here,” Annu nods, a beaded rainbow lanyard swinging from her neck. She translates a sign I couldn’t read. “It says, ‘This is the home of the cone animals. Make your own.’” She sticks four twigs into a pinecone, conjuring a little hedgehog out of nowhere. “These were all the toys our grandparents had. Finnish people grow up listening to the stories. Grandparents love to remind you they had nothing. They skied ten kilometers to school in the dark, in the snow.”

We come to a clearing, where scarlet lingonberries grow as if scattered atop the acid green moss covering flat bedrock in every direction. Thousands of fragrant pine trees shoot upward, tall and arrow-straight, filtering the light just so. Every now and again, the red top of a fly agaric mushroom stands out like a police siren, warning of the poison within.

Wind rustles the tree leaves, birds chirp. Annu hands me a bowl and says we won’t stop picking blueberries until it’s half full (not all the way full, as her ancestors insisted). She fills a basket with orange chanterelles, stooping to grab heather flowers and goat weed salad leaves. We snap the stems, a carrot-like smell affirming they aren’t poisonous. My hands are stained red, but I don’t care.

“The best things are the simple things. My grandma was picking mushrooms, berries and wild herbs, and now we will do the same.”

“These mushrooms you can use for coloring,” she gestures. “In Finland, everything is possible.”

“Any animals we should be watching out for?” I wonder.

“The bear is the king of the forest. But I have never seen one. When the Vikings came, we went to the forest and they didn’t find us. For Finns it’s always been a safe place. Many of us still feel this.”

Day-to-day stresses dissolve with each step, a notion so seemingly obvious it feels unnecessary to say so aloud.

“We take everything from the woods. We are forest people. We have found how to cope, through nature.”

Annu leads me to her open-air banquet hall, Korpela Laavu. Her colleague is smoking something delicious for a small group arriving later. Guests reach this magical setting via the art trail, and it’s what dinner party dreams are made of, pinecones scattered on tables, lamps swinging from the rafters, smoke swirling from an outdoor kitchen.

“Have you read the Moomins?”

I think of stickers slapped on Thermos flasks and lunch boxes, vomited out by some gargantuan entertainment conglomerate. And a certain collection of figurines once stashed in an upstairs loft.

“No. Never,” I smile to myself, not sharing the joke.

“So this is the time. You could try the audiobooks. Sit in the cabin and listen.”

We head back to the resort’s original cabin, Villa Armas. Built by Annu’s father, it was once the house she lived in.

“For your forest foot bath,” she says, filling a metal bowl with leaves and placing it in the cabin’s private sauna. “With some dried roses from my Grandma’s garden.” I love her immediately.

One in four Finns owns a mökki. The nation’s perennial top spot on the World Happiness Index starts to make sense. Annu rents out eight in total, each more luxurious than the last, and all with saunas. But I rather love mine, the coziest and most authentic. I have a go at chopping wood (disastrous) to heat the sauna, while Annu slides a beautiful piece of trout into a smoking box.

Cooking everything outdoors, she adds nothing but two cubes of sugar and some handpicked juniper. I fry up the mushrooms with homemade nettle salt. Dessert is toasted oats with apple slices cooked in butter, a vanilla sauce poured over and dotted with our precious berries. We drink raspberry leaf tea.

“This is as Finnish as it gets,” Annu advises. “Sauna, jump in the lake. Do as you feel. Everyone is different.”

“Any neighbors?” I consider going full Finn, braving the lake naked.

“We have three ravens that come to watch you. You might see a robin. You are getting it now.”

I swelter at 176°F, then splash in the eerily still water. Collapsing into bed, I peel a leaf from my foot, then sleep through The Moomins and the Great Flood.

A new day, a longer hike. Annu leads me to the painstakingly drained and restored Haukansuo bogland, squelchy underfoot and buzzing with life. She explains that bogs are crucial for protecting biodiversity, Hawkhill’s alone sinking around 16,500 tons of carbon per year. We stop for lady’s mantle tea and home-baked apple muffins.

Hawkhill has doubled down on regenerative practices, from buying used furniture to using only electric company cars. Annu’s team builds bug hotels, birdhouses and deadwood fences to support local wildlife, while restoring meadows and flower beds. They’re gunning for CO2 negative operations by 2030, working to compensate for all historical company emissions since 1963. I daydream of staying on, helping the cause.

“November is a special time here. A special time in the Moomins, too. Come back.” This time we end up laughing over my former aversion to the brand. Annu dreams of marketing a profound, indulgently melancholic “November” experience. “There would be one light, shining out in the darkness. You hear nothing. The lake is not frozen yet. Soak in cold water. Hot sauna. Beer and sausages. Nothing else needs to be done, because it’s November.”

We arrive at a stream that eventually leads down to Lake Poikkipuoliainen, in south Finland. Stopping to look, it occurs to me that I’ve not seen another soul in days. There’s no noise but for trickling water. I haven’t checked social media once, barely looked at a screen. I feel good.

Next morning, I enter the forest alone for the first time. I tune in to the trees, the birds, and the leaves rustling in the wind. And to the silence. There’s a timelessness here, a sense that the forest has always been here and always will be. I start to jog, listening to The Moomins and the Great Flood again.

Immediately I’m struck by its layers of complexity; clearly I haven’t given the little beasts enough credit. They’re multifaceted, allegorical, philosophical, even — like the forests that cover three-quarters of this mythical country. Moomins are deeply connected to nature; great long paragraphs describe Moominmama, Moominpapa and Moomintroll’s navigation of their folkloric surroundings.

It must have been late in the afternoon one day at the end of August when Moomintroll and his mother arrived at the deepest part of the great forest. It was completely quiet, and so dim between the trees that it was as though twilight had already fallen.

The vivid descriptions match the scene around me — even the time of year — powerful music accompanying the words. I stop every mile or so to take in this bizarrely immersive experience, finishing a chapter on a deck chair outside the cabin.

I’m Googling different Moomin books when Annu comes to say goodbye, hands full of my clothes that have blown off the balcony. Plus other things. “I don’t know if you will like it, but I’ve brought you something.”

Two brown paper bags, tied with white string. Inside the first, more of that wondrous foot bath mixture. “To take the forest home with you.” The second is heavier. I guess what it might be, from the look on Annu’s face.

Indeed, it’s my first foray into Moomin minutiae. Annu has chosen a mug depicting a dark November scene. Conversation turns to moonlit forest walks, lake swims. “Woolen socks, the fireplace and Karhu beer are waiting for you.”

Bound for the airport, the smell of pine wafting through the car windows and woodsmoke on my clothes, another quote rings in my head. “The world is full of great and wonderful things for those who are ready for them.” You can probably guess where I read it.

Amy was a guest of Hawkhill Cottage Resort. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply