Batavia, New York

On a brutally hot and wasp-swarming late summer mid-afternoon I walk our town’s old cemetery, as is my wont — hey, if I’m gonna live here for eternity I may as well get to know the neighbors. Walt Whitman swooned over one of this boneyard’s residents, and I have come to read the relevant passages to the boy who rests under the sod.

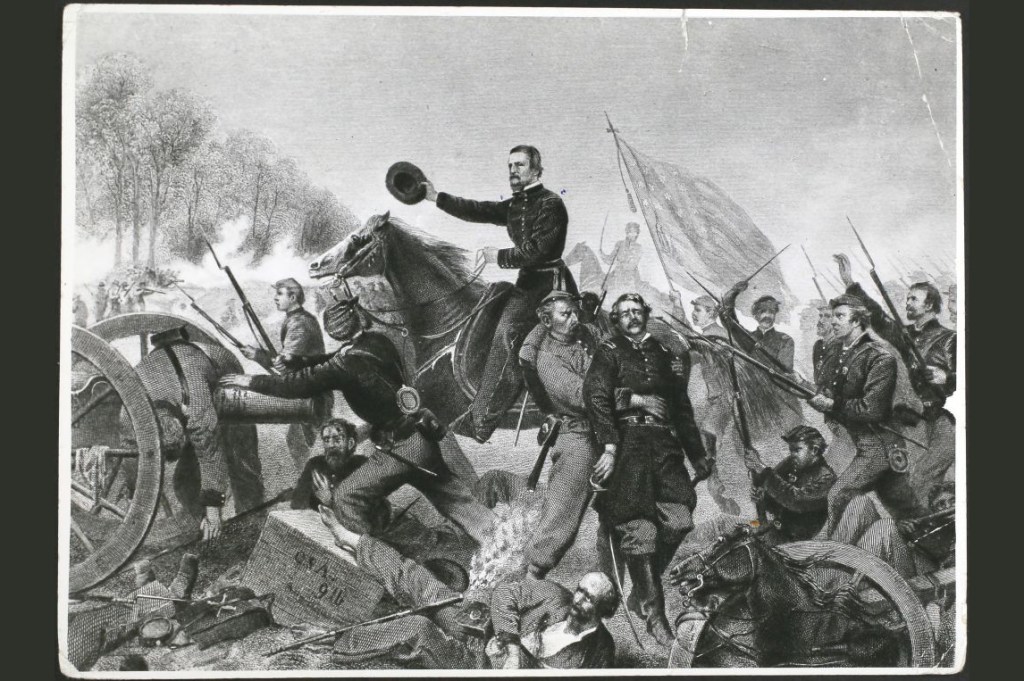

His name was Stewart Glover, and he appears in Whitman’s diaristic Specimen Days to illustrate ‘the terrible and tender realities’ of war-death. Glover, Whitman tells us, grew up in Batavia with his father, John Glover, ‘an aged and feeble man’. (I dunno: his gravestone says Pop lived to the ripe age of 83, dying in 1873.) The teenaged Stewart went off to college in the Badger State, and when war intervened he enlisted in Company E of the 5th Wisconsin Infantry. The lad ‘soon took to soldier-life, liked it, was very manly, was belov’d by officers and comrades’, records Whitman. (I love old Whitman so, as Allen Ginsberg once poetized, but reading him is like watching Rock Hudson movies: sore, ah, thumbs stick out all over.) In May 1864, after three years in Father Abraham’s army, young Stewart, now 21 years of age, found himself at the Battle of the Wilderness. In a foreboding plot device often found in films about superannuated cops who are set to retire next week — don’t go out on that call! — Glover, says Whitman, ‘would have been entitled to his discharge in a few days’.

We now enter ‘Billy, Don’t Be a Hero’ territory. Writes Whitman: ‘The fighting had about ceas’d for the day, and the general commanding the brigade rode by and call’d for volunteers to bring in the wounded. Glover responded among the first — went out gayly — but while in the act of bearing in a wounded sergeant to our lines, was shot in the knee by a rebel sharpshooter; consequence, amputation and death.’

Before his expiry Stewart Glover was transported to the hospital at Armory Square in Washington DC, where Walt Whitman, a volunteer nurse, comforted him in his final days. ‘He was a small and beardless young man — a splendid soldier — in fact almost an ideal American, of his age,’ testifies the poet. Stewart kept a diary, which Whitman read after the boy’s death. On the day he passed from this world he wrote, ‘to-day the doctor says I must die — all is over with me — ah, so young to die.’ Glover also penciled in this message: ‘dear brother Thomas, I have been brave but wicked — pray for me.’

Stewart and his family — except Thomas, for reasons lost to history — are buried next to the towering cenotaph erected to William Morgan, a local inebriate who was blackballed by the Masonic Lodge and took revenge in 1826 by revealing the oaths and secrets of the brotherhood in his book Illustrations of Freemasonry. Given that the Masonic initiate agreed ‘to have my throat cut across, my tongue torn out by the roots and my body buried in the rough sands of the sea at low water-mark’ should he ever apostatize, Morgan ought to have been prepared for what happened next. For his perfidy he was kidnapped by Masons and presumably drowned in the Niagara River. (His body was never found.)

Morgan’s abduction set off one of the more bizarre episodes in American political history, the Anti-Masonic agitation, which decimated the order and gave rise to an Anti-Masonic political party which captured the governorship of Vermont and the votes of the Burned-Over counties of Upstate New York.

Some called it paranoid, but then maybe ‘a paranoid is someone who knows a little of what’s going on’, as William S. Burroughs was fond of saying.

Which leads us to the hyperventilators huffing about an impending new Civil War, whose dim outlines are prefigured not so much by the acts of dimwit looters but by even dimmer tweeters and internet hysterics, placeless people who live [sic] in cyberspace and wouldn’t know their next-door neighbor if he farted in their face. Their exempla are the aments of antifa and pigmentation-obsessed race warriors: floating rootless atoms who can fantasize about waging war on their countrymen because they haven’t any, really. Back in the early 1980s, I did my minuscule part in thawing the Cold War by sending guitar picks and toothpaste to punk rockers in Poland. One of that noble land’s best bands, Dezerter, contributed to a compilation titled We Don’t Want Your Fucking War.

From six feet under, poor Stewart Glover, so young to die in America’s first Civil War, echoes the message.

This article is in The Spectator’s October 2020 US edition.