Most likely we experience it first as children, on summer vacation or a school trip: the sensation that something really important from a long time ago happened right here, on this very spot. Visits to our national monuments still stir the same old feeling, but, as I am long past childhood, a question arises that did not then. How is it that by stepping literally onto the spot, we step out of our own heads and into the past?

The conventional wisdom for the past half-century or so has been that historic sites demand explanation or, in professional jargon, interpretation. We all know the drill: the short introductory video, the guided tour sometimes with a “living history” component, audio-programs and headphones to guide us through on our own or cover what the docent misses, lots of labeling of artifacts, themed trinkets in the gift shop. Information abounds. And the motivation — to inform visitors about history — seems laudable. But what if there is something more to convey than information? Consider two spots along North Carolina’s Outer Banks, where I have returned now for over sixty years.

The Wright Brothers National Memorial at Kill Devil Hills marks the spot (spots actually) where, in December 1903, man first achieved controlled heavier-than-air flight. The story of how brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright, bicycle mechanics from Dayton, Ohio, did it is legendary and a sturdy evergreen for publishers and historians, that master-judge of great stories, David McCullough, most recently among them. The Wright Memorial is also home to another first, which bears on the question of why these places move us: the first National Park Service “visitor center.”

Today visitor centers are everywhere; educators and school groups would hardly know what to do without them. This one now looks as “historic” as the events it interprets and is very much a part of that story. Designed by Philadelphia architects Ehrman Mitchell and Romaldo Giurgola and opened in 1960, the building sprang from “Mission 66,” a program (to be completed for the Park Service’s fiftieth anniversary in 1966) to expand the parks’ visitor facilities and enhance interpretation of what it was visitors were visiting. The Mitchell Giurgola building, and others by other architects soon to come elsewhere, spoke the language of mid-century modernism at its zenith.

Kill Devil Hills even got a respectful rehab a few years back. It took fifty years from the time the Wright brothers first took off until modernism would give us buildings that looked like airplanes or at least suggested the spirit of flight, which is what this building does, modestly. With its flying-saucer roof, it evokes the space-age aesthetic that produced Eero Saarinen’s TWA Terminal at then-Idlewild Airport in New York. While it doesn’t quite soar like Saarinen’s superb Washington Dulles terminal of the same era, the Wrights did not exactly soar either. In fact, they barely got off the ground. But lift is lift, whether a few feet or into the stratosphere, and the building fits its time and the place. The 1950s and early 1960s was the last time when Americans still saw themselves as the world’s heavy lifters, as a people who got things done. This expanse of sand, where the Wrights got something big done in a small way, got in the Mitchell Giurgola visitor center the monument it deserved.

Inside, interpretation follows a chronological script from man’s first efforts to get off the ground with Icarus and Leonardo, through the Wrights and their European contemporaries, and on to the rockets and the jets. When you’re finished with the story, you can step into the adjoining pavilion underneath the flying saucer roof, where a ranger will engage in conversation about the full-scale replica of the flying machine that launched Orville on that twelve-second 120-foot-long flight into history. (The original hangs in the Smithsonian.)

Through the glass doors, it is just a few steps to the spot where it happened. There is not much told here that I did not learn in that old Landmark Series of schoolboy histories, in the volume on the Wright brothers. Facts are facts in history, or used to be, and the ones lined up here celebrate a tale of inventiveness that once had us rapt. Everybody these days has flown, but in 1960 when I first visited this spot, many still hadn’t, and the prospect of someday taking off, as the Wrights proved was possible, still thrilled.

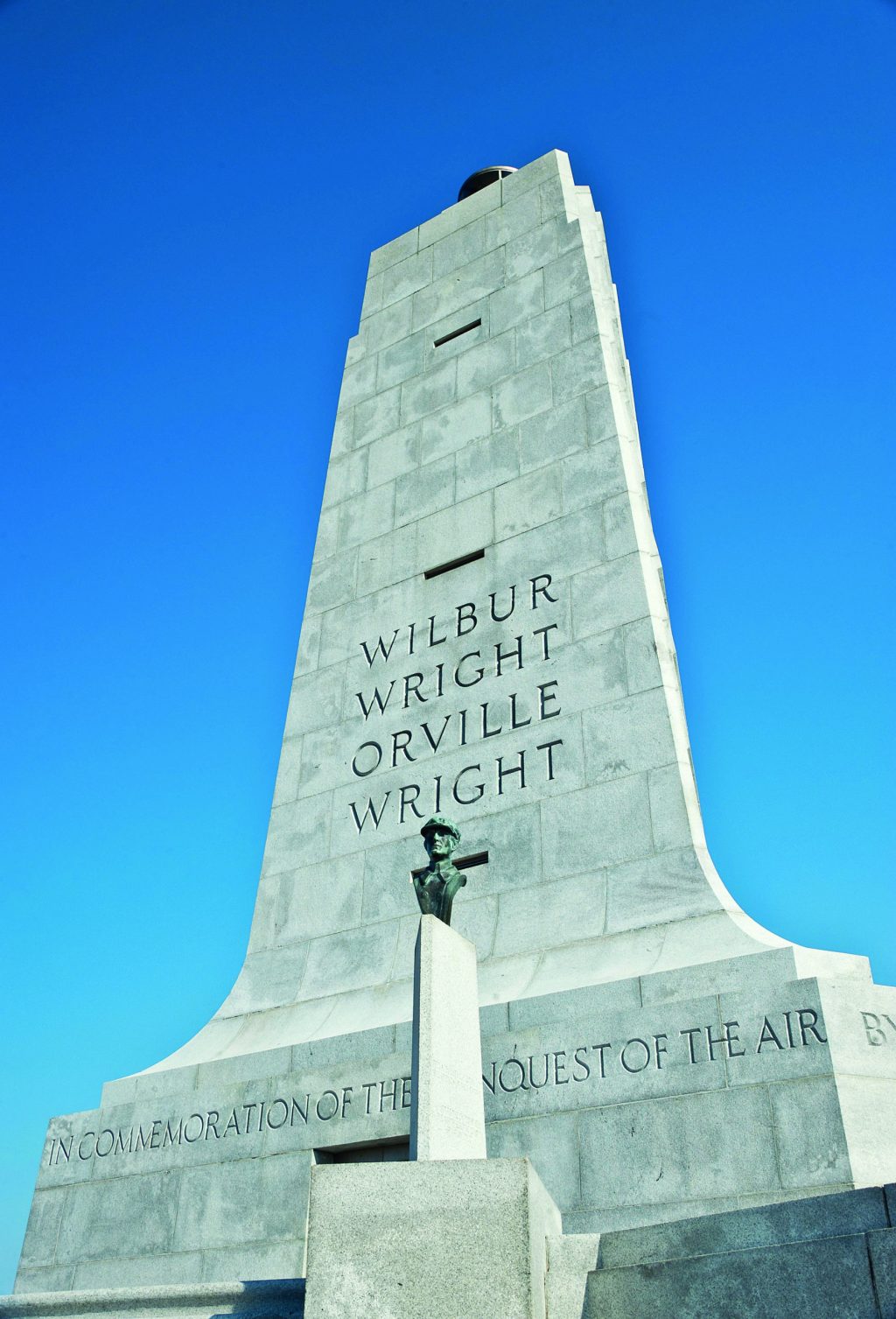

A moral story is told here too, pretty much straight from Ben Franklin. The Wrights had curiosity and native know-how but no specialized training; they failed repeatedly but never quit; they were careful observers and kept meticulous records; they studied the best that others had learned and weren’t afraid to ask for help. Though better as inventors than businessmen, they nonetheless made some money and became famous in their time. They got their first memorial twenty-eight years before the flying saucer visitor center and still in Orville’s lifetime (Wilbur died in 1912). The Wright Memorial Tower tops the ninety-foot sand dune called Kill Devil Hill, just to the south of the visitor center.

It too fits the purpose, for its moment. Dedicated in 1932, it was the work of New York architectural firm Rogers and Poor: a tapered triangular pylon sixty feet high with deco-ish bas-relief wings on two sides, the names of the Wrights on the third. At the base visitors read, in the best of monumental prose, the dedicatory inscription: In Commemoration of the Conquest of the Air by the Brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright / Conceived by Genius /Achieved by Dauntless Resolution and Unconquerable Faith. The message is as uplifting as flight itself and celebrates one of the great themes of modern times: man’s conquest of nature through science and especially technology. Stand on this spot, and it is a challenge not to feel awe for the Wrights’ achievement.

It is my habit to follow up Kill Devil Hills with a drive south to Cape Hatteras and its great lighthouse. A national monument administered by the same office as the Wright Brothers’, Cape Hatteras Light was first lit in 1870 and, at 198 feet, is the tallest lighthouse in the country. Its beam still flashes warning by night, its distinctive black-and-white spiral pillar an unmistakable marker by day. As mariners have known for centuries, Hatteras is a dangerous neighborhood. Close offshore lie Diamond Shoals and the “Graveyard of the Atlantic,” so called for the hundreds of ships and sailors lost there and resting on the bottom. In World War Two, German U-boats gave the Cape a darker moniker yet: “Torpedo Junction.”

Hatteras Light is grander architecture by far than either the modernist visitor center or the deco pylon at Kill Devil Hills, and it conveys the opposite message: man’s fundamental helplessness before nature and his own nature. Stand on this spot and experience an altogether different order of awe. At Hatteras even on a fine day, it is difficult not to think of nor’easters and hurricanes, pirates and blockade runners, deadly undertow and the threat that the sea might one day claim the great tower itself. In 1999, it was moved 2,900 feet inland to prevent just that.

A couple of days after a recent visit, an alert flashed on the Park Service’s Hatteras website. A piece of live World War Two ordnance (a 100-pound aerial bomb that had probably been looking for a U-boat eight decades ago) had washed up on the beach near the light, and a bomb disposal squad from the naval base at Norfolk had been summoned to deal with it. Everything was cordoned off, and the controlled explosion was audible miles away. Such nasties still turn up with some frequency in northern France and in British cities that suffered the Blitz, but in America they are rare. This one was a reminder of how close the enemy once came here too; its detonation needed no interpretation.

So why do historic places prompt awe and take us out of ourselves? The answer lies less with interpretation than preparation. Place triggers memory, but only if our memory is well-furnished. So, do your homework. Don’t rely on just the official spiel or bury your face in some travel app, last-minute as you cross the parking lot. Instead, skim again that old Landmark book from childhood, or read David McCullough on the Wright brothers. Brush up on Hatteras history with a local master like David Stick, or spend an evening with Dudley Witney’s The Lighthouse. Stock up, as Samuel Johnson admonished, before you sail: “He that would bring home the wealth of the Indies, must carry the wealth of the Indies with him.” If today’s travelers to our nation’s capital would bother to look up, they would see that proverb etched in granite on the face of Daniel Burnham’s great Union Station: “A man must carry knowledge with him if he would bring home knowledge.” Nowadays, such attentiveness is a lot to ask. But if you number among the few who still do attend to history, the prep will pay off richly when you find yourself on “the spot” at last.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2022 World edition.