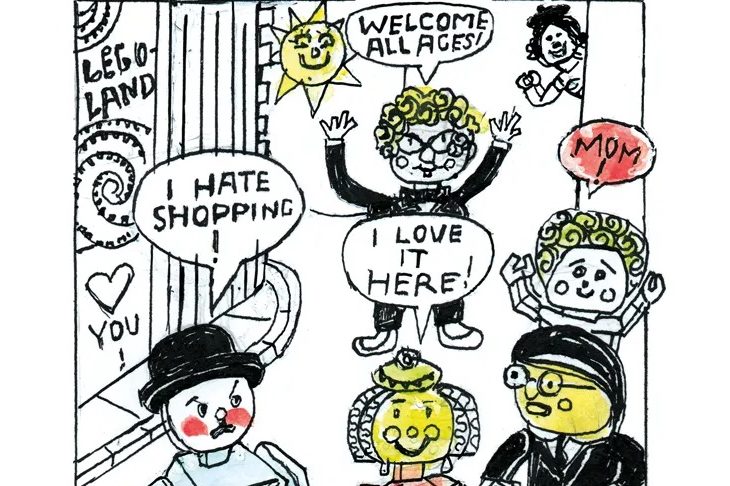

The empire of LEGO has many dominions and protectorates, with every year, it seems, new territories to conquer. There are theme parks; there are films of excruciatingly ironic sophistication; there are competitions to make bizarre tableaux that grip nations; there are highly controlled TV documentaries about life at the heart of LEGO in Denmark.

I don’t feel my life will be complete until I’ve spent a week constructing Hagia Sophia out of plastic bricks

It is an astonishingly powerful brand and its growth has been extraordinary to watch. Many years ago, it was just one building toy among many, like Meccano or Fischer Technik. Now, it is supreme. Some tremors were, however, observed last week when a plunge in profits was reported. Operating profits from the first half of the year fell almost 20 percent, the largest decline since 2004. Explanations were easy to come by — the steep rise in the cost of raw materials, for instance. Though sales were still rising, the sharp increase produced by lockdown was never going to continue at the same rate. The extraordinary run enjoyed by LEGO must be slowing, if not coming to an end.

The massive expansion of LEGO’s basic appeal means that there are parts of its range which even draw in people like me. I had it when I was a kid, of course. But it didn’t really come back into my life until about ten years ago. Somehow, I discovered that you could buy a model in LEGO of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater house. I was amused at the idea of building this great modernist villa in LEGO — I was still thinking of LEGO as a children’s toy — and bought it for myself as a Christmas treat.

The first set in LEGO’s Architecture range was released in 2008 — a model of Sears Tower in Chicago. It was a modest affair, consisting of only sixty-nine pieces. Most of the initial collection was of famous US buildings, including the Guggenheim Museum in New York, Wright’s Robie House and the Rockefeller Center. It has expanded in both geographical coverage and ambition.

They are the work of a very small group of greatly gifted designers and come out to the intense scrutiny of a small but committed community of LEGO fanatics. The scale of the minarets in the 2021 model of the Taj Mahal came under fierce criticism, for instance. There are strict principles that the designers abide by: one is that sets should not require the creation of a new type of brick. A new upward-curving corner roof tile was needed for the most recent set, a splendid recreation of Himeji Castle in Japan. It was unavoidable but, evidently, a major and controversial step.

The eligibility of buildings to be turned into models is an interesting question. I personally think that nothing with human statuary really works in LEGO, though they have attempted the Trevi Fountain — St. Paul’s, or St. Peter’s in Rome would be tremendous apart from this question. The LEGO community generally finds very repetitive building tiresome, which makes a good deal of architecture wearisome. A newish model of the Eiffel Tower, with 10,000 pieces and ultimately standing five feet tall, was in some quarters felt to be too much like hard work.

I’ve made five models, and their appeal is hard to overestimate. The most irresistible feature of the recent kits, such as the Great Pyramid, the much-criticized Taj Mahal and the glorious 2,126-piece Himeji Castle, is that you find yourself building ultimately invisible interiors. The interior structure of the Great Pyramid is laid bare before being closed up again; the sarcophagus chamber of the Taj Mahal; the intricate relationships of rooms and interior staircases in Himeji. Then you pop the roof on and never look inside again.

They take a few days to make, of careful planning, sorting, organizing and peering at incredibly tiny bricks, as well as a fair amount of cursing as you realize you’ve gone in a wrong direction — one stud out will do it. The illusion is beautifully sustained, but LEGO likes it to be clearly an illusion. The gardens surrounding Himeji have the studs left visible when they could be covered, to remind you that it’s only LEGO.

As an undertaking, I have to say the LEGO architecture sets are challenging but lead to some surprising insights — you understand the cantilever construction of Fallingwater once you’ve put it together, and appreciate the asymmetry of Himeji in a lot of detail. Am I the target consumer for LEGO? Clearly not — I don’t even keep the models hanging around once I’ve made them. Does it perhaps indicate a loss of direction, to devote the slightest corporate energy in appealing to a kiss-of-death punter like a fifty-eight-year-old London novelist?

Perhaps. I dare say the kids are still on board, and I very much hope they carry on with this glorious, eccentric, hugely absorbing line. I don’t feel my life will be complete until I’ve spent a week constructing, say, Hagia Sophia, the Centre Pompidou and the Sagrada Familia out of several thousand plastic bricks, some only two millimetres square, at the end of which the tips of my fingers will be purple, and positively throbbing with pointless achievement.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.