There are some cramped, unimaginative people who — I have been told — maintain that writing about wine is a bootless enterprise. Even more extraordinary, I have heard it rumored that there exist unfortunate sods who believe that it is a waste of time to gather with friends over food and wine while discussing the events of the day, the state of the republic, the repair of one’s soul. Fortunately, neither you nor I are acquainted with any such freaks, otherwise you wouldn’t be reading this column and I would not be sitting down to write it.

At the end of his brief, tantalizing book The Educated Imagination, Northrop Frye, the great Canadian literary critic (do you sense a passing adumbration of contradiction there?) notes that there is a sense in which learning to read literature involves answering the question “What is the use of something useless?”

Cutting to the chase and dispensing with all the intellectual foreplay, the answer is basically the same for reading literature as it is for drinking and appreciating wine: we don’t do it for any practical advantage. We do it for its own sake. From a meta perspective, I suppose you might argue that we do such things in order to enjoy them, but, really, in the end we do them to bracket the imbricated realm of “the in order to” and savor something for its own sake, absent ulterior motivations.

Of course, that in itself is a desirable condition, so I suppose you might say that “the in order to” sneaks in through the back door, adding a little backbone or trajectory to our revels.

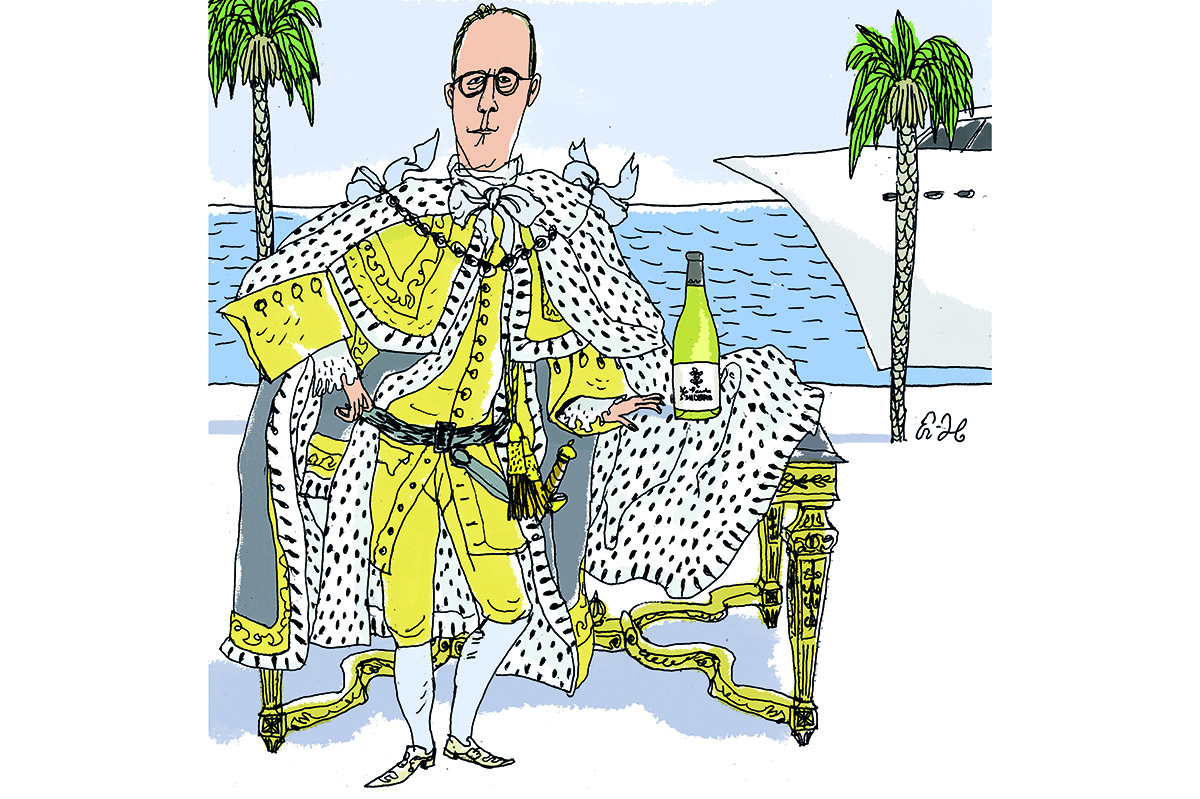

Anyway, that’s my story and I am sticking with it for the duration of this useful column on some advantages of things some people deem useless. More to the point, I write you from a semi-secure, undisclosed seaside location where my entire office repairs for a few days most summers. We walk about (but no one goes walkabout), swim, ride bicycles, go fishing and absorb the sun and sea air. We also read, silently and aloud, and we prepare and devour delicious food. And of course we indulge heartily in the fruit of the vine. Which brings me to the true point of this column: to pass along a handful of suggestions for your next summer outing with friends and acquaintances.

All the wines I am going to mention are what you might call outdoor wines: delicious, yes, but more suitable to the beach, the picnic, the freshly caught striped bass, the grilled sausage or ribeye on the patio than the formal dining room serving fancy food with sterling cutlery and crystal goblets on a starched white tablecloth.

Let me start with a couple of signal bargains. How about an approachable right-bank red Bordeaux, a blend of Merlot, Cabernet Franc and Cabernet Sauvignon, from Château Peybonhomme-Les-Tours? This fresh, agreeable Côtes de Blaye is both light and full-fruited, soft yet sturdy. The 2020 is only about $15-17, a steal. I hadn’t had it before, but, having been introduced, will be sure to improve the acquaintance.

You’ll want a pleasing but unpretentious white to go with that. I suggest you call on Château Graville-Lacoste, a dry, medium-bodied blend of Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon from Graves. The 2022 has an intriguing herbal quality — characteris- tic of Sémillon — a long finish, and, like the Peybonhomme-les-Tours, an unbeatable price of $15-17.

A baby step up the price ladder is the 2022 Raisins Gaulois Beaujolais from Marcel Lapierre, son of the storied Marcel Lapierre who makes some of the deepest, most complex Morgons in in all of Beaujolais. The son has made a straightforward, pleasing summer wine — “joyous and refreshing” said one critic, rightly — that has all the untroubled fruity frankness of Gamay with none of the brooding introspectiveness of the more expensive crus du Beaujolais clustered in the northern part of the region. The bottles we found were just over $20, another steal.

Another great find was 2022 “Mon Coeur” from J.L. Chave, whose distinguished wine-making family has been making wine in the Rhone since the late fifteenth century. You’ll pay a lot for the Chave Hermitage, but this 50/50 Grenache-Syrah blend boasts the dark fruitiness of Châteauneuf-du-Pape for $22-$23.

Finally, regular readers will recall the column I wrote some time ago about the growing trend of “dry Sauternes.” Yquem makes one, so does Suduiraut. And so does Château Rieussec. It is named, as are the other dry Sauternes, with an initial: “R” de Rieussec Bordeaux Blanc. It’s a blend of Sauvignon Blanc (54 percent) and Sémillon (46 percent). The 2020 is about $35. It is a lush, herbaceous wine that blooms and blossoms in the mouth. Perfect with cheese or shellfish, both of which, I am happy to say, were plentifully on hand during our little oasis from the workaday world.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply