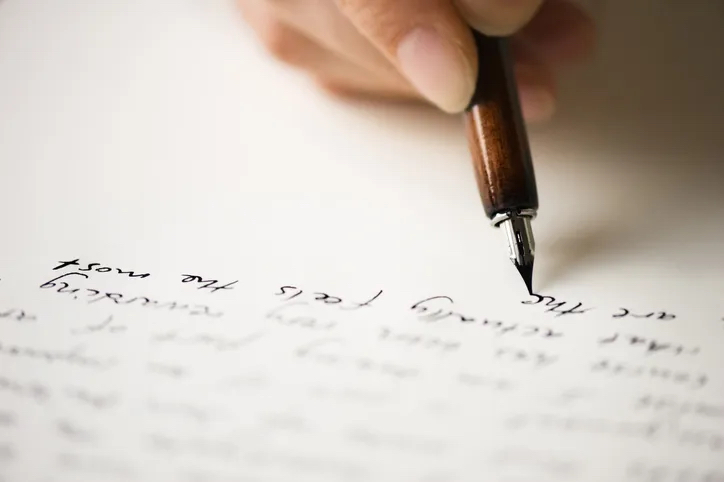

There are many good reasons, we’re constantly told, for millennials and Generation Z to resent their elders. What they can barely imagine, we took for granted: affordable housing, for instance. But there is another justification for their envy, one that is hardly ever mentioned: we wrote letters to each other.

Mine was the very last generation to do so. Bleak and empty was the day you didn’t find a stuffed envelope, in handwriting you recognized, waiting for you on the doormat. As well as being a sign you weren’t forgotten, letters could, at their best, be sources of sheer delight. Many went on for pages — it wasn’t unusual to find five folded sheets inside, written on both sides. There were sad letters, angry letters, adoring letters, funny letters, confessional letters, admonishing letters, guarded letters, letters which expected you to “read between the lines.” And often, it must be admitted, there were pointless and boring letters, with their flat banal accounts of surface facts and what the writer had done and when.

We were writing to each other in the last microseconds of a tradition which had endured for millennia

But for those of us blessed with a few good correspondents, receiving a letter was as intense a pleasure as we would ever get later on from great literature. It was instructive too: there were friends whose separate and equal existence you never quite believed in until you started writing to each other.

One friend described her platonic correspondence with someone we both knew as a “slow, steady, mutual exploration of our deepest thoughts,” and that often was about right. But it was also a kind of shared apprenticeship. You would hone your jokes, find ways of talking about your insecurities in ways which wouldn’t be embarrassing to the other party. You learnt to “tell the truth but tell it slant,” and throughout all of this you benefitted, because the writing of a long letter made you feel realer to yourself too, that your experiences and impressions didn’t just blow away like so much smoke.

Letter writing helped you refine what you thought about things. Why you preferred ferry trips to plane travel. Why smokers seemed preferable to non-smokers. Why you couldn’t stand your roomate or stop buying books.

Some correspondences were more honest than others: a pen-friend whose writing was self-consciously “literary” was a turn-off, not a comrade; just as bad were those letters too short and dashed off as a chore. But in the correspondences which survived you saw friends at their peak: probably better and more themselves in that form than they would ever be in another.

Letters were also a pleasure you had to wait for, which makes them firmly things of the past. People couldn’t be relied on to reply that day or even that week. Like so many of the best things in life, sending letters wasn’t cost effective either. It was time consuming, didn’t earn you any money, and was often just a form of play.

Only one copy usually existed, and it was considered private, not to be read by anyone but the recipient. This was the unspoken contract, even if it was occasionally broken. As such letters were as different as could be from the love-me, fear-me Instagram fakeries of today. The closest the modern world comes to them is probably the blog, but the whole point of letters was that they were tailored specifically to a single reader. When I discovered that one pen-friend was duplicating, verbatim, whole paragraphs to different correspondents, I was slightly shocked: this wasn’t playing the game at all.

I had many regular back-and-forth correspondences — with a pair of elderly writers I had sought out (people were generous with their time), or with a junior academic studying French and German literature, alive to absurdities of the world he was entering (the critical theory, the pomposity of diction) and relishing the chance to let go and kick around.

Another diehard correspondent was a fledgling unemployed scriptwriter on London’s Archway Road. In one long letter (selected at random) he dealt affectingly with his father’s declining health, his creative anxieties, the progress of a large spot on his face (day 3), a beautiful description of an air ambulance landing in Hyde Park and, in the light of a recent haircut — It makes me look like Gina Lollobrigida — his perennial inability to find a girlfriend.

Trying to be helpful, some nearby lowlife, he recounted, had suggested — absent anything more animate — he might make love with a loaf of bread. This prompted a flight of fancy, paragraphs long, on what kind of bread might be best for the purpose. A baguette? Too narrow and brittle. Organic wholemeal? Perilously abrasive at the crust. Artisan sourdough would be a treat but, given its intended use, a sheer extravagance. Finally, he settled on a donut (for staying power) coupled with a soft Marks & Spencer Seeded Batch. All this, needless to say, was theoretical and purely for my entertainment: he found a nice wife soon afterwards, without noticeable baking skills. But by then the letter writing had ceased.

Did they strengthen our friendships? Well, sometimes. They could give you a glimpse of a person at their very best and most confiding, and this could only be a boost. At other times, the letters were so much the liveliest, hidden part of someone that seeing them face-to-face — a different dimension — suffered by contrast. There were friendships which really only thrived on the written page, and when that stopped, the friendship sputtered out too. Yet unlike so many lost allegiances, they left thousands of words in their wake, and a drawerful of handwritten artifacts, to prove they’d once existed.

None of us knew that we were writing to each other in the last microseconds of a tradition which had endured for millennia. By 1998, the email was upon us, and though we carried on the practice hybrid-style for a while with long, tapped out screeds in cyberspace, the momentum quickly faded.

Suddenly it became more respectable, more moral to be terse and hurried. “What a very long email!” a novelist friend replied one day through gritted teeth, and I knew then the game was up. No longer would this ruminant, playful interface between two minds be quite socially acceptable. Writing such missives today would brand you at best someone with too much free time, at worst a psychopath. But we needed them, and surely still do.

We were also, often, genuinely grateful, and this was a part of friendship too. “Thank you for your letter, which lit up a gray morning and made me laugh so much.” “Thanks for your long letter, which gave me a boost and got me through the day.” “Thank you so much for writing — I read and reread it, it helped so much.” These were the kinds of things we wrote to each other, and wе frequently meant them.

Today, there are new forms of communicating undreamt of in those days, but none potentially so nourishing, strengthening, exploratory and humane. Meanwhile, the WhatsApps of our future adults ding all over the country: “Gr8 2CU last night. How RU today?” So tell me please, by text or tweet: what the hell have we done to ourselves?

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.