The pandemic of the past two years had many casualties — everything from lost lives to faith in bureaucratic and medical expertise. All-you-can-eat buffet restaurants were among the hardest-hit subsectors of the service economy. Buffets were already in steep decline nationwide by 2019, owing to evolving American preferences for fast casual dining and farm-to-table menus with Golden Corral as arguably the sole remaining buffet chain in America.

By 2022, even that venerable franchise — a Raleigh, North Carolina-based symbol of American excess and dependent on high gross revenues to offset narrow per-order profit margins — had seen its footprint shrink 25 percent, down to a mere 360 restaurants after losing eighty due to pandemic-related closures. Its most notable rival, Texas-based VitaNova Brands, had closed all but seventeen of their Old Country Buffet, HomeTown Buffet, and Ryan’s Buffet restaurants. CiCi’s Pizza, the nation’s largest pizza buffet restaurant chain, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2021, reporting nearly $100 million in liabilities. Locally-owned Chinese buffets, often the only buffet option in many small towns, faced similar setbacks, albeit with much less wiggle room regarding debt and negative cash flow. In fact, among the national buffet chains, only “faith-based” Pizza Ranch, with seventy-one locations in Iowa and a truly bizarre backstory, reported growth during the pandemic.

As someone who worked at the Golden Corral throughout the entirety of my college years, this development saddens me. The buffet, nearly impossible to justify on sanitation or food-wasting grounds (though the latter is due to concerns over legal liability), nevertheless represented a certain kind of bargain-bin American Dream. Here, for a fair price — $7-$10 in 2002 money, $12-$15 in 2022 — you could meet youir caloric needs and then some. For me, the Golden Corral sometimes provided two or even three square meals a day. For the legendary heavyweight mixed martial artist and amateur wrestler Dan Severn, whom I interviewed in 2021, only an encyclopedic knowledge of the buffet restaurants between Michigan and Arizona helped him keep his weight above 220 pounds while he pursued his Olympic dreams.

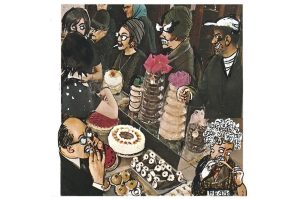

The thing about buffet food, particularly the sort dished out by the Golden Corral or a half-decent Chinese buffet, is that it’s usually serviceable. It might sit out for long stretches, but if you arrive right as the restaurant is laying out lunch or dinner, you’ll have access to a hot, fresh meal. On top of that, it’s choose-your-own-adventure: you can eat nothing but greasy fried chicken or gooey crab rangoon, for example, or if you were an athlete jonesing for high-quality protein, like Dan Severn or myself, you could binge on rotisserie chicken, baked salmon or other healthier options. And if all you could afford that day was a single meal, you could sit there for an hour or two and surpass the 2,000-calorie plateau with ease. As someone who spent four years cooking and eating this food, I appreciated its utilitarian nature: it did what it promised to do, which was fill us up. It was this ability to meet the demands of diners at a single reasonable price that led to the heyday of the American buffet around the turn of the century.

In the early 2000s, the Golden Corral and its VitaNova Brands competitors printed money as they expanded across the American landscape. At their respective peaks, the Golden Corral boasted over 500 restaurants, with VitaNova’s three buffet restaurant concepts combining for more than 1,200. The buffet, like Walmart, appeared to be an inextricable, perhaps even an essential, component of working-class American culture. Neither buffets nor that low-cost retailer offered the best of anything, but they offered a lot of everything for modest prices.

Despite challenges from Amazon, Walmart remains a fixture in the corporate landscape — and is every bit as utilitarian and unpleasant to shop at now as it was then. But buffets, always places where customers “assumed the risk” attendant with consumption of food sitting for long stretches under heat lamps or in refrigerated trays, were transformed by the safetyism associated with the pandemic into disease vectors for which no mere sneeze guard could offer mitigation. Even now, as the Golden Corral strategizes for its post-pandemic resurgence, its ideas for revitalization involve leaning into prepared foods, takeout and delivery.

The fate of the traditional buffet, delivering the sort of low-cost cuisine that sustained myself and Dan Severn, appears to rest with the nation’s thousands of Americanized Chinese buffets. For many of these family proprietorships, alternatives to simply setting out the food, taking your money, and hoping for the best aren’t feasible. For most restaurateurs — in some cases immigrants or first-generation Americans still pursuing the actual American Dream — only providing all that customers can eat will give their own families everything they need. The golden age of the buffet franchise might be over, but small businesses can still harness American gluttony to good ends. In America, the gospel of working-class food culture remains the same: blessed are those who hunger and thirst, for they shall eat until full for one flat price.