For the left, the world has always been, and always will be, a scandal. In this American election year, it has not escaped their anger and disgust that of the two presumed candidates for a second residential lease on 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue the incumbent is eighty-one years of age, while his challenger is seventy-eight. Yet that societies should be governed by their elders was taken for granted through all of human history down to very recent times. This was owing not to their experience alone, but to the fact that premodern people lived substantially in the past, recognizing that it — as Faulkner said — “is never dead, it’s not even past.” It is all we really we have, our sole sure reality, the present being ungraspable and the future yet to come, if indeed it ever arrives — a thing we can never be assured of. The intrusion of America upon history changed all that, it being the only society in history that has always lived, as Wendell Berry (the Kentucky farmer, novelist, poet and essayist) once noted, in the future to a degree that is almost occult. For the American people, broadly speaking, the past is either dead or it is bunk, and the present, being unreformed and highly unsatisfactory, leaves them with only the future to believe in.

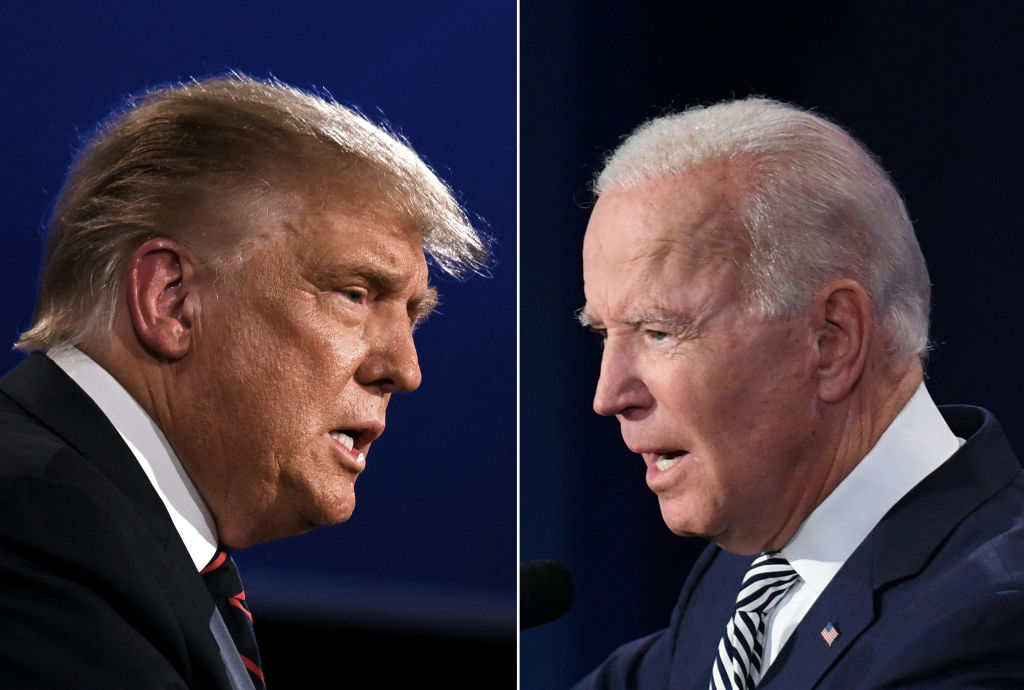

This explains in part why American leadership have been so lacking in competence since the Founding era. The French have a phrase for men who refuse to act their age: “les vieux jeunes hommes.” In France, it refers principally to middle-aged and elderly narcissists who dress and otherwise behave as if they were still in their twenties or thirties. Here, the “old young men” — more accurately, perhaps, the “young old men” — persist in ignoring the past as an irrelevancy, or worse; paradoxically, their inflexible ideological attitude prevents them from conceiving new ideas and looking for ways of applying old ones to new problems. This is the history of the Biden administration reduced to a single sentence.

In every premodern society, old age and the elderly themselves — not the men only, but the women as well — were venerated for their longevity and its presumed benefits. For the past century and a half or so, both have been patronized while youth and the young have been glorified, thus encouraging what is euphemistically called the “senior” generation to think and act young (besides looking, in a pathologically sexualized world, as youthful as possible for as long as possible). As for young people themselves, they are increasingly resentful of their elders for not moving over fast enough and allowing them to get on with the job of creating a future that really will be futuristic, to the point of defying (or denying) biological and metaphysical reality.

It may be that they have a point to make here, though they are failing to make it. Because if the tribal elders have not earned their position at the head of contemporary society by arguing, advising and governing wisely like the graybeards they are, they have no just grounds for claiming the respect due in the past to the age, experience and wisdom that compensated for decreasing physical vitality and stamina. This is especially so as the aging refuse their generational responsibility to instruct the young in traditional wisdom, preferring instead to play along with them — excusing or overlooking their ignorance, inexperience, enthusiasm, and confusion — from their own vanity, narcissism and inertia, their unworthy desire for the approbation of youth, and their determination to be remembered as having been on the “right side of history.”

While the United States has never been known — not since the 1820s, at least — for the quality of its senior statesmen, it must be plain to anyone with a working knowledge of American history that the twenty-first century is not a golden age, despite the miracles of near-Biblical proportions being worked by modern medicine. Jefferson, Adams and lesser-known remnants of the founding generation had genuine wisdom to impart to their successors, though it must be acknowledged that few of them wished to hear it, as Jefferson complained to his former rival in their final year of life. Senior British statesmen such as Pitt, Palmerston, Gladstone, Disraeli, Salisbury and Thatcher had valuable advice to offer those who came after them. But these were statesmen in whom the past was alive. By living exclusively in the future, modern politicians, in Americanized twenty-first-century Great Britain as well as in the United States, have nothing more of value to say in retirement — to anyone — than they had while still in full career. Moving ahead in cosmological time, they were going backward in every other way.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply